![]()

PART I

The role of social work in end-of-life care with older people

![]()

1

The ageing journey and the end of life

In this chapter, I set out the main themes of the book:

• Seeing ageing as a journey through life which we all follow.

• Understanding that the end of life is part of that journey, even a culmination of it.

• Identifying practice strategies for social work with older people in later life as they move towards the end of life.

• How the idea of citizenship social work encapsulates those strategies.

Main themes

Over the first half of the 21st century, rethinking services for older people is going to be an important priority in many countries. Why? Because during that period the number and proportion of older people in the world population will increase naturally as a result of people living longer. This will affect most countries, although the patterns of change vary. As we saw in the Introduction, population data and projections for the future can offer an idea of the changes that we can expect, but do not tell us about their social and personal consequences. It is useful to build on that with information specifically about ageing. We can put information about our own country in context by using international variations to compare the impact of population structures in different countries. I have listed some accessible sources to help you do this at the end of this chapter.

One often-mentioned statistic is the ratio of older people dependent on younger people who can support them economically. This indicates the pressures on a society better than information about simple increases in the proportion of older people in the population. This is because it indicates the ease with which a national economy can support its older people. For example, the UK is likely to have a higher proportion of adults of younger working age to support its rising number of older people than many other European countries and Japan because of immigration in recent decades. Migrants are more likely to be younger and have larger families than more established populations, and so are more likely to contribute to the ability of an economy to support older people in its population. Some unwarranted assumptions lie behind statistics like this, however. For example, focusing on this ‘dependency ratio’ could wrongly imply that people in later life are dependent economically and in other ways on younger people or that economic factors are the main things we should be thinking about when we consider older people’s lives or services for them.

As a result of population changes, a fairly settled view (a ‘political and social settlement’) of the role and social position of older people in many societies is inevitably changing. This book proposes that social work practice in social care services needs to change by including older people’s approach to the end of life.

In doing so, I address a failing in social care policy for older people. Social care policy often sees them as part of the administrative category ‘adults’. As a result, we do not focus on particular needs and interests of people who are in later life. Most policy on ageing emphasizes their social and healthcare needs, rather than broader aspects of their role in social life. The result is that older people are in a policy ghetto focused on problems they present to state social and healthcare services. I argue that policy should aim to enhance their lives in the same way that policies for children aim to enhance their development, or promote employment for young people, or good housing for families. Policies for older people should start from enhancing the experience of ageing and older age groups and increase the opportunities available for a positive lifestyle and well-being for older people. We should not start with the problems they present to our services.

Why does policy fail older people? We used to see old age as a ‘threshold’ category, but this is now inappropriate. To explain: people reached the threshold of becoming a pensioner or a ‘senior’. In their early 60s, they stepped over thresholds from working life and from being in the centre of their family. Soon, they would step over another threshold: decline towards death, in their mid to late 60s. For a while, when Western market economies required it, some people retired from work in their 50s or even earlier, either willingly, accepting generous retirement packages to free opportunities for younger people or reduce employment costs, or unwillingly, as industrial change and decline wiped out their work. They also began, with medical advance and healthier lifestyles, to live longer. Retirement stretched into many people’s 80s. Some older people experienced a long period of poor health before reaching death at an advanced age. Medicine became better at keeping people alive and maintaining their independence even though they suffered from long-term disabilities or health conditions. Well-off people could enjoy a life of leisure pursuits. Others, perhaps less publicized but more common, found that they scraped a less exciting existence.

How we see the end of life thus becomes more important to people in later life, because the thresholds between work and family life to a later life and then from old age into death have become separated and we have created a new stage of life. The early stages of old age are now an extension of normal living. It becomes clearer that later old age is about the process of coming to the point of dying. Without the opportunities that a happy retirement on a reasonable income can offer, this extended end-of-life process can seem interminable to poorer people who are frail and ill. Longer periods of ill-health and increasing disability and longer periods of an existence with little worthwhile achievement both suggested that it would be worth being able to make the choice to decide to end life; hence, the rise of concern with assisted dying, helping people to take their lives if they seemed worthless. Later life seemed an increasingly long prelude to end of life.

Reflecting the change in the political and social settlement for older people, the first part of this book identifies and builds upon five main themes in services for older people at the end of life that are relevant to social work practice. They are:

1. Ageing and the end of life are positive parts of our journey through a total life experience. Provision for older people must enhance their journey through their whole life, not be a separate service ‘delivered’ to meet ‘needs’ defined by other people’s assumptions about, and focused on, their health and social care needs.

2. Older people are citizens. Therefore, services for them must emerge from their citizenship, starting from valuing older people as participants in their communities. If we devalue ageing and older people, we de-citizen them and take away some of their citizenship. As a result, we should aim to be positive about the value of older people in our society and of positive opportunities for them. If they have lost value we must re-citizen them.

3. Care is part of a wider positive policy for older people, including social care and end-of-life care. Care is not an optional add-on. It is a natural part of human relationships. We see care as central to children’s development and essential between husbands and wives and life partners. It must therefore be a significant element of provision for older people. We should not see care through a ‘provision of services’ lens, but recognize it as a valuable aspect of relationships in later life in the same way as it is for all other age groups. This means focusing on care as part of essential social and community relations, not as a substitute service to deal with social and health problems. Incorporating dying well into later life is part of mutual care in our social relationships, not something to be denied and avoided. This reflects the reality that dying is closer to older people than most of us, and caring in later life must be included in our citizening and in services for older people.

4. Health and social care services should be multiprofessional and community focused. Although I focus in this book on social work practice, it can only exist as part of wider services, connected with other professionals and the services they work in and with the needs of the community of older people and their families.

5. Advance care planning is crucial in end-of-life care and social care for ageing people. Because planning for social relationships and end-of-life care in older age groups enhances choice, opportunity and well-being, it is integral to citizening. Older people benefit from planning for their social relationships as they age and so that they can die well.

Each of these positives suggests services for and professional work with older people must be as life enhancing as services and professional help for children, families and all the other people social and healthcare provide for. We are too often stuck in the assumption that old age is a less important phase of life: vitality comes from work and family responsibilities in adult life, but in later life death will not long be postponed. Instead we must provide for a valued and valid later life, leading to opportunities to die well. In this chapter, I want to explain my reasons for emphasizing these themes. If we think of older people as citizens, they must be able to contribute to society, not just take from it, and the important characteristics of their stage of life must be provided for. Among those important characteristics is appropriate provision for the end of life. I start from the idea of ageing towards the end of life as a journey, and in subsequent chapters in the first part of the book, I look at the other themes.

The concept of ‘journey’

Most people are ambivalent about ageing and they may see death as a final end to life. This is so even if they believe – for example, through commitment to the Christian, Hindu and Islamic faiths and other religions – that some aspect of their continuing identity such as a spirit or a soul continues beyond death. Ageing is not a good thing in many people’s eyes; they resist it or see it as bringing them problems. Western culture values youth; becoming older is not valued. Neo-liberal and capitalist societies see the working life, personal independence and individualistic competition in markets as natural forms of human society, devaluing non-work time and cooperative and mutual forms of support in life. This neglects the role of care for others in human relationships as also a natural form of human relationships. Most people see living as an individual and personal journey through society. Death is not-life, the opposite of living, the end of the journey.

All of this means we do not value ageing and dying well as part of the journey that defines our humanity and identity. Yet, we all age and we all die, so old age and dying are parts of life like our childhood, our teenage period, our adulthood, our work life and our midlife. All of these phases of human experience contribute to the happiness or dissatisfaction that we experience as we live. Until we have died, we continue to have experiences, and that includes the process of dying. By seeing old age and dying as part of everyone’s human journey, we are saying that it is possible as human beings to make the best of this part of our lives. Robertson (2014) emphasizes how by identifying important transitions in later life, we can see this as a positive journey like the earlier stages of our lives. By thinking about the transitions we may make in later life, we can also avoid thinking of later life as marked by chronological age – the number of years we have lived. In the past, we have thought of the retirement age as marking the beginning of old age; but this marker is shifting upwards and in any case does not reflect physical changes that affect older people. And the physical changes do not reflect changes in expectations, or the social life that we lead. When people call 70 the new 50, comparing the physical and psychological experience now with the experience a couple of generations ago, they are identifying changes in the cultural experience of ageing.

While Robertson’s (2014) focus on transitions is useful, therefore, in not seeing these changes too negatively, he reflects common social attitudes about later life. In Table 1.1, therefore, I list important transitions that he identifies, and attach some of the positive aspects of living that can emerge from them.

Table 1.1 Transitions in later life

| Robertson’s transitions in later life | Ways of living through transitions in later life |

|---|

| Retirement | Creating and achieving new personal development and education goals |

| Moving home | Creating a secure and positive environment for living, even if there are limitations |

| Becoming a grandparent | Building respectful relationships with your children as parents and maintaining new contact with young people |

| Relationship breakdown | Making new relationships and social connections |

| Becoming a carer | Valuing caring and helping roles |

| Bereavement | Memorializing important aspects of past relationships and incorporating them into a new lifestyle |

| Acquiring a long-term health condition | Managing health conditions successfully |

| Entering a care environment | Creating a new lifestyle in care |

| Preparing for the end of life | Completing life tasks and relationships |

Source: adapted from Robertson (2014)

Just as we experienced caring in childhood, between adult partners, friends and relatives throughout that life journey, so we should value care when it appears as part of ageing and completing that journey in dying. Helping professions, such as social work, and informal carers among family and friends should aim to contribute to the best age and dying experiences. This is important because their care is an integral part of the society and the community caring within these aspects as well as throughout our life journey. Social care and social work should avoid dealing only with the problems of ageing and end-of-life care. Instead, they should contribute to a society that cares about providing for ageing and dying well.

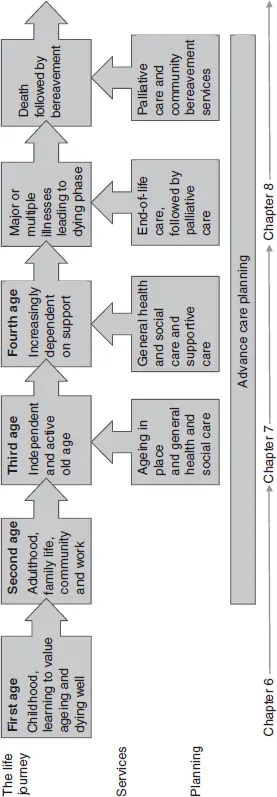

In Figure 1.1, I have set out ‘ages’ of the life journey, picking up a commonly used concept. Here, later life is divided into a third and fourth age.

Figure 1.1 The life journey through ageing towards the end of life

Although Shakespeare and many other writers have talked about the phases that people go through in life as ‘ages’, there are problems with doing so. As our cultural experience of chronological age has changed, so too has our experience of phases of ageing. ‘Phases’ can become too prescriptive. We might come to think that everybody lives their life according to these phases. We might even come to act on the assumption that they should live their life in this way and there is something wrong with them if they don’t. A general problem with calling such phases of life ‘ages’ is that they become attached to people’s chronological age. Consequently, we might not only assume that people do or should live their lives in the same order, but they do or should reach each phase at a particular age or stage of life.

To take these general criticisms further, recent conceptualizations of later life, particularly the idea of the ‘third age’, are contested. Laslett (1996) formulated the idea of a ‘third age’ of life in which older people developed active and fulfilling lifestyles unconnected with their employment. This idea originally comes from the French ‘universities of the third age’ in which older people come together to share their learning and experience and renew their education, not focusing on preparation for work, but taking up education as a fulfilling experience. These have grown into a worldwide movement. There is also a connection with Pifer and Bronte’s (1986) ‘third quarter’ of life, which includes changing attitudes to work in the chronological age period of 50–75 years. Another connection is with Neugarten’s (1974) distinction between the ‘young-old’, who remain active, and the ‘old-old’, who become more dependent on health and social care.

The ‘third age’ idea proposes that retirement or other changes in middle age, such as children leaving home to begin independent lives, offered people opportunities and ‘agency’ – that is, psychological and social control – to put new ideas about how they wanted to live their lives into action. Many people receiving health and social care services feel that maintaining control of their life experience as they aged was important, even when they had ‘high support needs’ requiring a lot of health and social care provision (Katz et al., 2011). The opportunity to fulfil personal aspirations fits with ideas about having a positive later life, and has similarly been very attractive in public and policy debate. Seeing this phase of life positively, however, raise...