- 186 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Monsters are fragmentary, uncertain, frightening creatures. What happens when they enter the realm of the theatre?

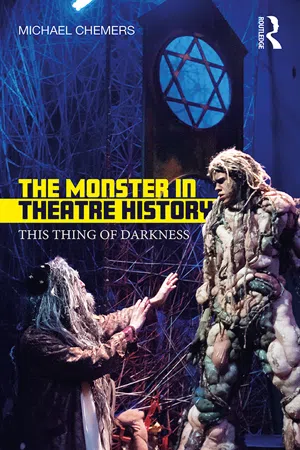

The Monster in Theatre History explores the cultural genealogies of monsters as they appear in the recorded history of Western theatre. From the Ancient Greeks to the most cutting-edge new media, Michael Chemers focuses on a series of 'key' monsters, including Frankenstein's creature, werewolves, ghosts, and vampires, to reconsider what monsters in performance might mean to those who witness them.

This volume builds a clear methodology for engaging with theatrical monsters of all kinds, providing a much-needed guidebook to this fascinating hinterland.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Monster in Theatre History by Michael Chemers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Folklore & Mythic Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Caliban’s legacy

In the final scene of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Prospero, a sorcerer and the former Duke of Milan who is now in exile on a distant island, has just completed an intricate scheme to restore his position. Using his magical powers and those of his unearthly servants, Prospero has brought all his enemies together and exposed the schemes against him, including a rather shaky plot to murder him and take over the island by the jester Trinculo, the butler Stephano, and Caliban, a monster. Trinculo and Stephano are servants of Prospero’s enemy Alonso, so Prospero charges him to “know and own” them – to take responsibility for their actions. The third conspirator, Caliban, the “thing of darkness,” Prospero acknowledges as “mine” (V.i.2346–50). Prospero is in a forgiving mood, since his own schemes have come to fruition. Moreover, his magical powers render him immune to such a threat, so it seems he does not take the plot very seriously; nor do Trinculo or Stephano, who were blind drunk during the whole affair, and whose sobriety has brought abject contrition along with the clarity of a hangover.

Caliban, on the other hand, was deadly serious.

Native to the island, Caliban is the son of Sycorax, an Algerian witch who was banished to the island years earlier; his father was, according to Prospero, some sort of demon. Sycorax was immensely powerful in magic – Prospero attests that she could “control the moon” (V.i.2344). Prior to his arrival with his daughter Miranda, Sycorax was the undisputed queen of the island, but due to her own evil she grew herself “into a hoop” (I.ii.260) and died, leaving Caliban alone with the many strange creatures of the place until Prospero and Miranda appeared. As to Caliban’s exact form, Shakespeare gives us very little direction – like all the best playwrights, he leaves significant artistic leeway to his actors and costume designers. We do, however, have Prospero’s ungracious description: “Then was this island/Save for the son that did litter here/A freckled whelp, hag-born, not honor’d with a human shape” (I.i.285–7) Although this last phrase – “not honor’d with a human shape” – is often taken out of context to describe Caliban, the somewhat convoluted grammar of the full sentence actually insists that Caliban does have a human (albeit freckled) shape. To Prospero, he barely counts as human in any case. But he is not precisely human: later, Alonso will call him “as strange a thing as e’er I looked on” (V.i.290) and Prospero replies that he is “as disproportion’d in his manners/As in his shape” (V.i.291–2). Meanwhile, the jester Trinculo seems to think he smells like a fish, which has led several artists – including Johann Heinrich Ramberg – to represent an ichthyoid Caliban, even though Trinculo is clearly an idiot (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Stephano, Trinculo, and Caliban dancing; detail from Johann Heinrich Ramberg’s The Tempest, II

Source: Cornell University Library.

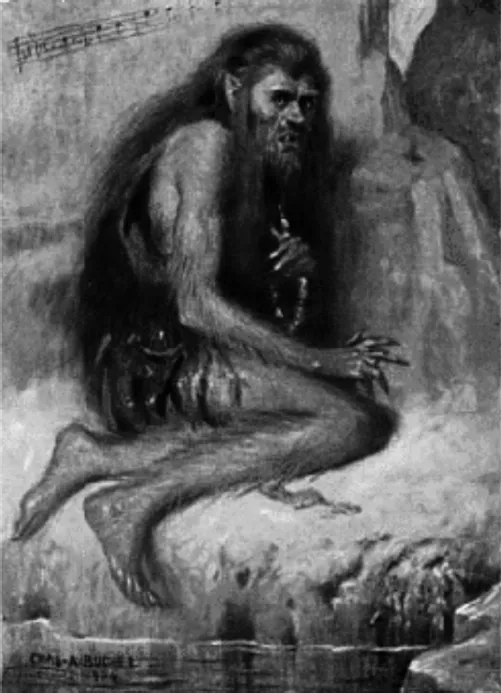

But Herbert Beerbohm Tree, represented in a drawing by Charles Buchel (see Figure 1.2), played a more mammalian, proto-human monster in a 1904 revival at His Majesty’s Theatre, with shaggy hair covering his body, claws on his hands and feet, garbed in leaves, with pointed ears and wicked fangs. A century later, Djimon Hounsou played the role with his body unadorned except by patches of vitiligo, strange scales, and ritual scars in a 2010 film directed by Julie Taymor (see Figure 1.3), perhaps to emphasize a postcolonial critique (see below).

Figure 1.2 Charles A. Buchel’s depiction of Herbert Beerbohm Tree as Caliban, from Shakespeare’s Comedy The Tempest (London: J. Miles & Co, 1904)

Source: Courtesy of the British Library.

Figure 1.3 Djimon Hounsou as Caliban in Julie Taymor’s Tempest (2010)

Source: © Touchstone Pictures.

It is tempting to see Caliban’s monstrous appearance as a sign of some inner moral turpitude, but such an equation is not quite so simple. When Prospero and his daughter first arrived on the island, years before the play’s action begins, Caliban was quite impressed by the new immigrants. He reminds Prospero that the sorcerer was kind to him, and instructed him how “to name the bigger light, and how the less/That burn by day and night” (I.ii.334–5). In return, Caliban revealed the island’s natural and supernatural secrets to Prospero, facilitating his quest to fill the power vacuum created by the death of Sycorax.

Prospero’s daughter Miranda also once had a close relationship with the monster. “I pitied thee,” she reminds him, “Took pains to make thee speak, taught thee each hour/One thing or another” (I.ii.353–5). But the Edenic happiness of these initial encounters was disrupted when Caliban attempted to rape Miranda, for which crime he is severely, and continually, punished. Prospero subjects Caliban to innumerable abuses – verbal, corporeal, psychological, or magical in nature. Unrepentant and rebellious, Caliban assumes a role familiar to Shakespeare’s audience – that of the comic, truculent servant.

But unlike Ariel, Trinculo, and Stephano, Caliban is not a servant, and this tinges his comic behavior with deadly malice. He is a slave, held against his will and forced into servitude. Prospero makes no bones about this – he and Miranda refer to him as a slave with punishing regularity. Unlike a servant, a slave has no contract, no rights, no privileges, and no expectation of betterment, and for this reason a twenty-first-century Western reader, with twenty-first-century Western prides and prejudices, will find it difficult to discover a clean moral perspective from which to regard Caliban. His attempted rape of Miranda is deplorable, inexcusable. At the same time, many postcolonial critics of Shakespeare have argued convincingly that Caliban’s situation mirrors in many ways that of the colonial subject. King of his island, Caliban was displaced by invaders who seemed like friends, but turned out to be conquerors. A monster, Caliban’s agency is likewise monstrous. What choices can he make apart from violence and horror? And what can he do but fail, and fail again?

So this, then, is the “thing of darkness”: suffering evil but capable of evil on his own; able to learn but also to twist knowledge to a darker purpose; a creature who did not know himself until he was taught that he was a monster. This is what makes Prospero’s acknowledgement of Caliban as “mine” so compelling. Is the old wizard finally accepting the totality of his own failures as a master, and his own responsibilities for Caliban’s monstrosity, including that the possibility that his project to “civilize” Caliban has failed due not to Caliban’s weaknesses, but his own? Prospero has rewritten his own sad story, and now almost everyone is forgiven, liberated, or getting married. Prospero forgives Caliban for being a monster, after which the monster says he will “be wise hereafter/And seek for grace,” but will this search be on Caliban’s own terms, as a restored king and a “natural man” with all the tools he needs to become enlightened, or is he merely to be abandoned on a barren island, native rendered an exile in his own land, a king with no subjects? In acknowledging that Caliban, warts and all, is “mine,” does Prospero not recognize another monster – the one he sees in the mirror?1

Ultimately, of course, neither Prospero nor Caliban may be said to have “agency” for they are not real, living subjects, only characters in a play written four centuries ago. They are doomed to reinscribe one another’s monstrosity perpetually, or at least as long as this play is read and performed. These are cultural products, and as such they have no particular rights for which to fight. We are free to dissect them as we will, and perhaps we will be forgiven if we repeat the error of centuries of theatre historians and critics who “read too much” into Shakespeare. At the end of the day, after all, The Tempest is not about magicians and monsters, but about us – we who watch the parade of transient theatrical productions for the joy of coming to grips with this text in a new way every time. What gives significance to Prospero’s actions is the direct relation we make to our own actions, for the enrichment and betterment of our own persons and societies.

Not for nothing, then, does Jeffrey Jerome Cohen cite Prospero’s description of Caliban as a “thing of darkness” in his landmark essay.2 I use the phrase as the subtitle of this book because I, inspired by Cohen’s essay, aspire to recognize myself mirrored in the monsters I see in my culture. No life lesson can be more confusing than the realization that the thing of darkness we despise is housed within, not without. To take on the all-too-necessary step of coming to terms with our demons in order first to understand and then, perhaps, expel them (or at least put them to some productive work) is perhaps the most difficult human journey. There is no knowledge that we resist with greater persistence and invention, perhaps because we know, deep down, that the thoughts we publicly ascribe only to monsters are, in fact, our own; to snatch, to devour, indeed to rape and kill – to take what we want, to give vent to the poisons that torment our minds by becoming one of that supernatural ilk who, unbound by human decency, do what they wish without fear or guilt or remorse.

To what lengths will we go to avoid such self-examination? Our impulse instead is to revise our favorite stories, and even our personal or social histories, in an attempt to render any stain invisible. But as we focus exclusively on the light, we give our monsters room to grow and be about their business in the unexplored darkness. Predictably, the more we attempt to erase our monsters, the more often they appear. Is it any wonder that at the time of writing this book, the culture of monsters is as vibrant as ever, with its endless procession of books, movies, and plays that rehash and reinvent monster tales?

How to hunt monsters: the seven theses for the stage

In the Introduction to this volume, I articulated why the study of monsters is culturally significant, and why the study of monsters in performance is particularly meaningful. In this chapter, we will discuss the mechanics of the application of Cohen’s Monster Theory to performance analysis. In his 1996 essay, Cohen lays out seven key ideas for engaging with what he calls “monster culture.” These ideas provide a foundation for a variety of approaches to the study of monsters, and I have found them very productive for generating methods for application in performance.

Thesis one: the monster’s body is a cultural body

Cohen envisions the monster as a “free radical” in the systems of cultural exchange humans generate, and the important role that performance plays in the generation of “hierophants” – or interpreters – of the “glyphs” that monsters represent. All cultural products perform this act in one way or another – all must employ the library of signs available to the communities in which they appear, or they will not be understood. They may also create new signs, of course, but these must also be explained and linked to an extant matrix of semiosis, or they will leave audiences scratching their heads. But performance is particularly grounded in the particular moment of its creation. Fuseli’s horrific painting The Nightmare, currently residing in the Detroit Institute of Arts, is unchanging (except by the arbitrary ministrations of time that may decay its paint), but it is available to be interpreted and reinterpreted by each of us as a self-contained semiotic ecology. Performance, on the other hand, comes into being and then vanishes in the same moment, so it must be perpetually recreated. It is experienced in time and space as reality, not as an abstraction or representation of reality. Of course, a rational audience understands, intellectually at least, that there is a difference between the action that is happening and the action that is represented, and willingly suspends disbelief in order to allow the performance to weave together fantasy and reality. The experience of being profoundly moved by a performance is not one that can be adequately described with purely rational language – it involves a kind of provisional contract with the imagination that in other contexts would be considered psychotic. It is a liminal space; not insane but not completely sane, not pure fantasy but not pure reality either – a space in which things that are separate can become joined, in which things that are singular can become multiple. We value this because it is deeply important to our construction of identity both social and individual, but also because it is thrilling and wondrous.

All performance involves this liminality, but monsters are special. They add to this complex alchemy another unstable element: fear. Reading Shelley’s Frankenstein or Poe’s “The Raven” in the comfort of one’s home, or contemplating Fuseli’s The Nightmare, can certainly provoke a horrific confrontation with darkness. We may change as we engage these cultural objects, we may undergo processes of discovery and transformation, but they do not. Performance changes constantly; in fact it may be said to be in a permanent state of transformation. It provides visceral immediacy. It is as capable of provoking terror as it is of evoking horror – outright fear as well as deep anxiety. Turner conducted research that demonstrated how people in audiences at performances exhibit neurobiological ergotropic reactions, including increased physical arousal, heightened emotional response, and augmented sympathetic discharges, such as increased heart rate, blood pressure, and sweat secretion, pupillary dilation, and inhibition of digestion; the same reactions, in short, that are produced by certain psychotropic drugs. They experience this systematic physical change as what Turner calls a “ritual trance,” a state of mind t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: the dramaturgy of empathy

- 1. Caliban’s legacy

- 2. Prometheus the thief

- 3. Presumption

- 4. The vampire trap

- 5. Toys are us

- 6. Boo

- 7. Hairey Betwixt

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index