- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A Druid looks at quality control for product and service industries, amplifying from his earlier book Right first time . Some highlights: Quality is a religion, with the same trappings and pitfalls as other religions; humanity can be distorted, but not abolished, by managerial decree and organizatio

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 THE LONG-NEGLECTED TOOLS OF QUALITY

Man is a tool-using animal,Without tools he is nothing,With tools he is all.Thomas Carlyle

‘With tools he is all’? Not quite. Many an amateur mechanic possesses all the tools of motor maintenance yet his car still sits immobilized because of some mechanical defect. Carlyle was only partly right. Ownership of the tools for the job is, of itself, never enough, to be effective tools have to be used, with skill and purpose.

The tools of Quality Management – the statistical tools used to transform process data into managerial control information – have been available to us in the West for long enough, yet until recently have generally hung rusting and unused. For how long? Since 1801, when the German mathematician J.K.F. Gauss published, in his Theory of Number, the knowledge which forms the basis of modern Statistical Process Control. This mathematical concept was taken up during the 1920s by an American physicist, Walter Shewhart, and turned into an elegant and powerful system for the controlling of process variables in engineering manufacture.

Thereafter it fell into disuse. The vast majority of Western manufacturing disdained the use of these statistical methods, preferring to depend instead on out-moded methods of inspection of product after the manufacturing event, when it is too late to make pro-active corrections. They preferred to produce scrap, and then complain about it. So its advocates – prophets without honour in their own land – turned to post-war Japan.

And Japan turned to them. Embracing this doctrine of frugality called statistical quality control. Adopting its methods. Adapting them. Improving them.

These tools of the mind, forged in Germany, tempered in America, honed to lethal sharpness in Japan, then found their way back to the hemisphere of their origin. In consequence the business landscapes of the Western world have undergone an upheaval – a Quality Revolution. It has shaken Western managerial thinking like some kind of earthquake of the intellect. This eruption of interest in total quality has sent its shock waves deep into the heartland of the manufacturing sector, its seismic rumbles down the slopes of the service sector, and its tremors along the business littoral into every commercial nook and cranny. With what kind of effects? Patchy, to say the least. Ranging from the cataclysmic to the inconsequential.

In some zones entire sectors have been laid waste. Once-proud companies, held together with nothing more than a crumbling cement of complacency, have collapsed into tumbled heaps of dereliction. Now they are no more than names in industrial archaeology.

Of the survivors a few, very few, have learned from the tremors of change. Their structures, stripped of vain adornment, are now buttressed with the girder-work of solid quality management, foundations strong enough to support their future. But many, it seems, look at the cracks in their organizational walls and wonder what to do next: a bit of plaster here, a prop or two there, and hope the insurance premiums are paid up to date.

It is as if Vesuvius had erupted and, having obliterated the decadent Pompeii, produced nothing more than a few bright Roman candles and a multitude of sputtering squibs.

For some reason too many of our enterprises still have not adopted the tools, techniques and philosophies of Statistical Process Control and Total Quality Management. They have the Means, they have the Material, but for some reason they lack the Mind. What is it that constrains them?

The constraints must lie within their culture.

Culture. There is a word more prone to misinterpretation than most. Even to utter it in the presence of some of our industrial chieftains is to meet the dismissive and contemptuous ‘Culture? Don’t talk to me about that kind of claptrap. We are here to work. I am the boss. I tell ’em what to do and they do it. We don’t want any nonsense about “culture” in this outfit, thank you.’

That man has just made a cultural statement, although he is not aware of it. He has told you that the cultural climate in his organization is of the power style. He has also claimed that within this culture all power belongs to him; he is wrong, none of us can ever begin to be so omnipotent. He also denies the very existence of a thing called ‘culture’.

You can no more avoid culture and its effects than you can avoid breathing that mixture of nitrogen, oxygen, trace gases and murky pollutants that we dignify by the description ‘fresh air’. We are surrounded by culture, enveloped by it, drenched in it, permeated by it. Avoid it? The grave itself is no refuge from it. We are creatures of culture.

What do we mean by ‘culture’? Is it as Matthew Arnold (in Culture and Anarchy) reckoned it to be – ‘Culture being a pursuit of our total perfection by means of getting to know … the best which has been thought and said in the world’? Total perfection sounds much the same as zero defects, so this might be a fair definition of quality culture, but it is not a deal of use to us as a working specification.

Do we mean music of such haunting beauty that it speaks to us of the eternal within the temporal? Or the splendour of Dance? Or the new vision of a familiar reality bequeathed us by a long-dead painter? Or the majesty of language created by poets to enrich our imagination? Hardly. Culture these may be, but again we can hardly put them to work; they are too precious to be serviceable to our needs.

Do we then, when we refer to ‘culture’, mean it in a nationalistic sense – Mexican, or Swedish, or Russian, or Japanese …? Not really. This also affords us too constricting a concept.

Then what do we mean by ‘culture’?

We mean the climate of belief, assumption, taboo, convention, supposition, folk wisdom, acceptance, understanding… all the nebulous things which together make up the psychological environment within our organizations; an environment which conditions attitudes, moderates behaviour, guides action. These are all to do with people’s minds. If we are to make any changes to organizational performance we must address these cultural things; we must make fundamental change by changing minds because only ‘mind’ is fundamental. This is the principal purpose of implementing total quality management in the organization. Its primary purpose is to improve process and product quality, it must do this in order to acquire and retain credibility, it must pay for itself in the measurable terms of money earned by better quality practice. But this by itself is not enough, it is too superficial, too temporary. The secondary – yet principal – purpose of doing it is to change the culture in order that performance change will endure.

But every organization has its own unique culture – how are we to come to grips with such infinite variety in order that we may formulate some kind of working plan, a kind of road map, to help steer our actions in any organization regardless of how different it might be from all the other organizations with their own unique cultures?

What we need is some kind of management ‘model’, or ‘theory’, a standpoint from which to assess this entity called ‘the organization’. We need something like …

Viewpoints

You walk through the city of Birmingham, you see the city. Then you drive through it in your car, you see the city, only now it looks a little different. You travel through Birmingham on the railway, again you see the city, only now it seems much more different. Finally you climb out of Birmingham Airport and you see the city unfolding beneath you, now it looks completely different. Four different viewpoints, which of these is the ‘real’ Birmingham? Obviously, they are all equally real, only now you know a lot more about the shape of Birmingham than you did after your first stroll through its streets, because each viewpoint afforded its own facet of that place we call ‘the city of Birmingham’.

Now let us suppose there is a city called ‘work’. It stands on a flat plain encircled by hills. From the summits of each of these hills we can gaze down upon the plain. Each hilltop provides its own unique view of the place called work. Each of these high vantage points is a ‘managerial model’, a concept, from which to examine the object of our enquiry. The more vantage points we have the wider our understanding of what we are looking at. This is what management models are for, this is why these sierras of the mind were erected, as standpoints to afford us different perspectives. Like their geographical equivalents these peaks have names: there is Mount McGregor, familiar to us for his Theories X and Y; there is Herzberg’s Heights, whose view divides the rewards for working into hygiene and motivational factors; there are many more summits in this range of hills, many viewpoints.

Each of these viewpoints makes its own unique observations about the nature of work; not one of them is able to say everything, there cannot possibly be One Universal Model of Everything, but each says enough to be of service. But before we completely lose ourselves in a trackless wilderness of words which might be ceasing to mean much let us reconsider why we are bothering to contemplate these matters.

We are assuming that organizational performance is a direct expression of company or corporate culture.

Using the philosophies and techniques of Total Quality Management we aim to improve company performance.

We believe performance change will follow from cultural change.

We shall therefore try to consciously plan and bring about cultural change, by changing minds.

This is a daunting and demanding undertaking. We are speaking of radical change (radical meaning ‘at the root’, from the Latin ‘radix’), by addressing the root causes where culture has its origins. To help guide us we need a management model of ‘culture’. We have one. It is the Harrison-Handy model. Again, like any model this one does not – cannot – say all there is to be said about its subject, but it says enough to be of use to us. This is a high and appropriate vantage point from which to explore one aspect of the culture of work.

The Four peaks of Harrison and Handy

The purpose of a model is to simplify by uncluttering what would otherwise be too complex a picture to be understood. It is rather like a colour filter in a telescope, which takes out the dazzle in order that you might see more clearly. Somehow by looking at less of the total it reveals more of the essence.

Being engaged in that business described somewhere in the Old Testament as ‘the labour of the foolish – the multiplying of words’, I work from an office converted from one of the bedrooms of my house in North Wales. This stands on the eastern flank of the Vale of Clwyd, and a score or so miles to the westward the ramparts of the Snowdon range rear skyward to prop up their tent of cloud. The view through my window is constantly changing. It is not possible to see exactly the same view twice. Each of the windows’ four vertical panes frames a particular peak on the Snowdonian horizon. At any time one particular peak stands higher than its fellows, then the curdled Atlantic sky sweeps inland on the prevailing wind to obscure it so that now another one seems tallest. A shift in the wind’s direction and the canopy concealing another summit is drawn aside like a magician’s cloak to reveal a higher pinnacle. The alterations to this rippling horizon are dependent exclusively on the capricious climate, they are beyond the observer’s control. Even so, window-gazing can be a pleasant and sometimes rewarding way of passing time, in fact a consultant once remarked that I was conceptualizing. Dreaming a future.

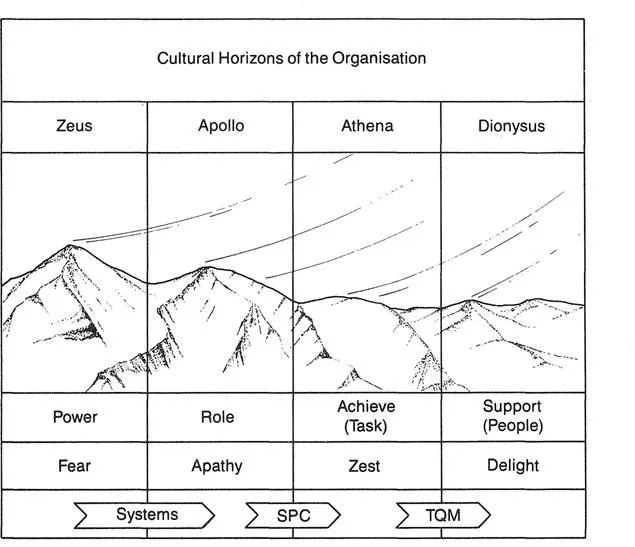

I seemed to have spent ages gazing abstractedly through the window of my office at the horizon of smoky-blue hills to the west, looking for some unifying concept to encapsulate the cultural complexities of all the many organizations who were my clients. I needed some kind of mental structure which whilst embracing their diversity would filter out the dazzle and serve as a model to describe them all. Then when I met the Harrison-Handy model it dawned upon me that I had been staring at it all the time without knowing what it was. Those four peaks seen through my window were analogous to the four styles of culture in Harrison and Handy’s model. Now they had new names. They are called Power, Role, Achieve (Task) and Support (People).

If you look at Figure 1.1 you will see these cultural summits depicted in an arbitrary order of comparative height. All that this model tells us is that in any organization any one of these styles predominates, and it is usually backed up by a second style. Just as each organization has a prevailing cultural climate which could be described fairly accurately (but not totally) by this model, so each of us – the organization’s members – has a preferred style as described in this repertoire of four styles.

This is not to pass value judgements on any of these styles or on any person adopting any particular style, though it is hard not to do so. The model is morally neutral. There is no ‘best’ or ‘worst’ style, but there could well be styles which are appropriate or inappropriate to a company’s situation or its declared business mission. These are matters of opinion. Let us look into the nature of the four styles:

POWER

This is the marionette-master style of managing. Always autocratic – ‘I am the boss’, or even more ‘I am the company’. At its best it is paternalistic – ‘I look after my workforce like a father’ (yes, Dad, so by the definitions of your scheme of things your subordinates are perceived as dependent children); at its worst authoritarian (subordinates are seen as naughty children).

Companies, or even parts of companies, operating under this cultural style enjoy at least the benefit of having strength at the top. Or what looks like strength, but might in fact be something else. The boss-figure is the focal point; all orientation in the company is internally directed towards ‘pleasing the boss’. When he is displeased he shouts. Like his patron-deity Zeus he smites with verbal thunderbolts those who incur his wrath. He seems to be aroused to anger all too easily – even the most trivial of transgressions is enough to unleash his biting tongue. Fear stalks the corridors of his company, but at least it keeps people in order. This is one way of running the whelk-stall, and some people seem to like it, especially the favoured few who are elevated to the rank of boss’s crony and hence enjoy the privileges which only the boss is empowered to dispense.

ROLE

In this style the System is the system and all depends upon the system. It is a bureaucracy, feeding upon paper in order to prod...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Figures

- Preface

- 1 The Long-Neglected Tools of Quality

- 2 Deming’s First Point

- 3 Deming’s Second Point

- 4 Deming’s Third Point

- 5 Deming’s Fourth Point

- 6 Deming’s Fifth Point

- 7 Deming’s Sixth and Thirteenth Points

- 8 Deming’s Seventh, Tenth and Eleventh Points

- 9 Deming’s Eighth, Ninth, Twelfth and Fourteenth Points

- 10 Who Needs Religion?

- Select Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Right Every Time by F. Price in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Industrial Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.