Introduction

Given the increasing ubiquity of cell towers, GPS satellites, smartphones, beacons, miniaturized sensors and other contemporary means of registering location, it is easy to forget that location technologies in fact have a rich history that long predates modern, industrialized contexts. Take, for instance, language, one of humankind’s oldest “technologies.”1 Language has long been understood as “locational.” Remarking on the Yaghan people of Tierra del Fuego, travel writer Bruce Chatwin notes that “the Yaghan tongue – and by inference all language – proceeds as a system of navigation. Named things are fixed points, aligned or compared, which allow the speaker to plot the next move.”2 One illustrative example of the legacy of location technologies can be seen through the traditional wayfinding and navigation practices of the Marshall Islanders. The Marshall Islands are comprised of more than 30 coral atolls and islands “spread out in two parallel chains over 800 km in the eastern part of Micronesia” in the Pacific Ocean.3 Navigation in this region is especially difficult due to “strong, opposing equatorial currents.”4 And, yet, the Marshallese have managed to navigate and move between the islands of this dispersed archipelago in small outrigger canoes for hundreds of years by developing a “comprehensive system of wave piloting” that utilizes “land-finding technique[s] for detecting islands by how they disrupt ocean swells and currents.”5 Being able to “know as they go”6 and overcome the “disturbance of distances”7 is the result of kōkļaļ – the ability to read “navigation signs,” including the relative strength of radiating wave patterns (which indicate the distance towards land) and of specific wave signatures (which indicate the direction of land) and other natural signs.8

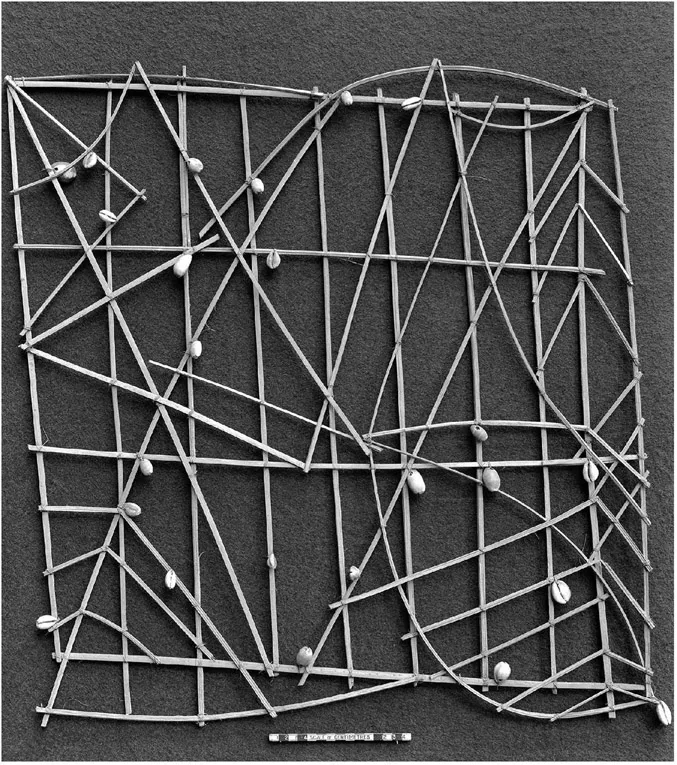

These “navigation signs,” or mental lines of knowing,9 have been captured within stick navigation charts, an early location technology that the Marshal-lese used for representing “oceanographical phenomena” and other positional information relating to the archipelago (see Figure 1.1).10 Stick charts consisted of “narrow strips of the centre-rib of a palm leaf […] arranged in certain forms and positions, and […] tied together with lengths of palm fibre.”11 Within these charts, “the strips indicated […] the wave front of the swell caused by the prevalent winds,” while “the curved rods indicate that, while the swell movement is checked in the neighbourhood of an island, in the open sea it sweeps on unhindered,” and “areas where two swell fronts intersect are those where rough water may be experienced.”12 Meanwhile, islands were “marked by small shells which are tied on to the palm-rib framework.”13 Much of this knowledge is now supplemented by other,

Figure 1.1 Marshall Islands sailing chart made of sticks and shells, tied with palm fibre

more recent location technologies, including outboard motors, navigational equipment and telephones.14

The Marshall Islanders’ creation and use of stick navigation charts provides a rich example of longstanding forms of location technologies.15 What is valuable about this particular example is it encapsulates many of the key themes of the book as a whole and of the specific arguments of the present chapter. This opening vignette points to the merits of extending our gaze beyond established Anglo-American and European contexts if we are to develop a fuller understanding of the longer histories, as well as more contemporary take-up and use, of location technologies. The attention to stick navigation charts also highlights the value of adopting a more expansive understanding of location technologies than, for instance, is captured by the term “locative media”; rather, location technologies extend beyond GPS-enabled smartphone use to account for other, creative practices of “making do.” It also draws out the often very close connection between location determination and micro, meso and macro forms of mobility as well as immobility that is tied to location. The Marshall Islands example also highlights the need to be attentive to cultural specificities of use, and the many complexities associated with these, and reveals how location technologies (like mobile media) are often unsettled and subject to, as well as part and parcel of, larger processes of transition and transformation.

Location technologies in international context

In their 2009 book Mobile Communication, Rich Ling and Jonathan Donner document the rapid rise and global significance of mobile communication. “In a very short time,” they write, “the [mobile] device has had a major impact on the way we interact and organize our lives,”16 adding, “we cannot overemphasize the importance of this basic connectivity to hundreds of millions of people.”17 At the time of their writing, however, location capabilities were only just beginning to be recognized. In a passage describing the mobile phone as the “Swiss Army knife of technologies” due to its manifold functions, they note as an aside that “there are also devices that provide location information.” This is something that has since undergone rapid change. Not only are mobile phones now something that we often take for granted,18 but location finding and location data have become core (rather than subsidiary or marginal) aspects of much mobile use in different parts of the world.19

Thus, while initially a somewhat specialized pursuit or preoccupation,20 locative media have subsequently grown significantly as a result of increasingly rapid commercial development (around smartphones, mobile maps, GPS integration, location-sensitive social media apps and so on) driven by wider public interest and mainstream take-up. Commensurate with the growth, commercialization and increased ubiquity and take-up of locative media, a significant body of scholarly work has emerged that seeks to chart and make critical sense of these location-related developments.21 In our own contribution to this literature, we noted that, by 2015, “diffusion and interest in [location] technology were forging ahead” in important ways, and yet a key gap in the research field had become clear:

There is much to suggest that locative media are spreading and being adopted and adapted around the world. Yet the published research literatures, especially in English, do not reflect this trend. Rather, like many other areas of cultural, media, and communication studies, locative media research is modeled by imaginaries, assumptions, and standpoints from a restricted palette of countries, societies, sociodemographics, classes, and subcultures.22

An apparent lack of detailed critical attention to date to the wider international take-up of location technologies is curious given mobile-cellular uptake rates now stand at 97 per cent globally.23 More telling in the context of smartphone and app-driven take-up of location services is the fact that, despite significant pricing discrepancies that favour developed over developing countries, mobile broadband continues to be “the most dynamic ICT market,” with “mobile-broadband penetration” reaching 47 per cent globally in 2015 (a 12-fold increase since 2007), then set to more than double again to an estimated 97.10 per cent in 2017.24 However, as the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) notes, despite the “high growth rates in developing countries and in LDCs [least developed countries], there are twice as many mobile-broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants in developed countries as in developing countries, and four times as many in developed countries as in LDCs.”25 Looking just at the African continent, Wendy Willems and Winston Mano draw on the same 2015 ITU data to note, “while only 1 percent of Africans have access to a fixed landline, nearly 74 percent now have a mobile phone subscription” – a figure which had risen to nearly 78 per cent by 2017.26 They further note that “internet access has similarly grown significantly, primarily because of the rise of internet-enabled mobile phones,” with the number of Africans with access to the mobile internet jumping from 14 million in 2005 to 162 million by 2015.27 And, returning to the global outlook, according to one data analysis firm’s forecast, “the user base of smartphones and tablets will more than double to 6.2 billion by 2020,” driven by cheaper smartphones and more accessible data plans, with much of this growth likely to come from India, Indonesia, China, Mexico, Brazil and Turkey.28

Thus, a key ambition of this book is to take heed of and pay close attention to these global developments and respond to persistent calls to “internationalize” media and communication and cultural studies,29 in order to develop a coherent account of location-based technologies and their cultural, economic, political and social dimensions of use, as understood outside of established Anglo-American and European contexts. In exploring these issues, our aim with this book is to build on the important body of established scholarship on location services within Anglo-American, European and related contexts (often referred to as the Global North) and work on mobile communication in the Global South,30 complementing both sets of literature with the best available scholarship on location technologies in the Global South. Although concepts such as the “Global North” and “Global South” are sometimes seen to obfuscate more than illuminate and, according to cultural studies scholar Nikos Papastergiadis,31 have been usurped by neoliberal agendas, the reality is that most locative media and location technologies research still focuses upon Europe, North America and Australia.32 We thus use “Global South” and “international” intentionally to attend to the broader call to challenge our conceptions of what location and locative media and technologies means in the lives of the non-dominant populations in order to begin to construct a fuller, more truly global, composite portrait of the present state of location technologies internationally.

The task of “internationalizing” the study of location technologies is an important one, as we highlight in this volume.

Everyday practice

An internationalizing focus is valuable, to borrow Willems and Mano’s words,33 in “de-essentializing” and “provincializing” locative media research by suggesting, for example, that the “compelling tangle of modernity and technology”34 might productively be understood less as something that flows from “centre” to “periphery” than as something that develops according to, and which follows, multiple trajectories that are subject to uneven spatio-temporal patterns and rhythms of development (where certain technologies, for instance, take off faster in particular places and times and not others due to complicated social, economic, political, infrastructural and other factors).

The “de-essentializing” impacts of an “internationalizing” focus are also in key respects a direct result of field research that pays ...