![]()

Part I

Overview and Methods

![]()

1

The Psychology of Attitudes, Motivation, and Persuasion

Dolores Albarracín, Aashna Sunderrajan, Sophie Lohmann, Man-pui Sally Chan, and Duo Jiang

A quick look at the front page of the New York Times shows headlines, such as:

- 12 Oscar Nominations for The Revenant

- Syrians Tell a Life Where Famine is a Weapon

- Cruz Did Not Report Goldman Sacks Loan in Senate Race

- What to Expect of G.O.P. Debate: Escalating Attacks

- Terrorists Attacks Kill at Least Two in Jakarta, Police Say

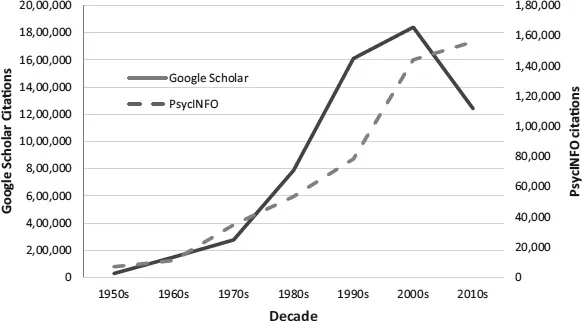

Each and every headline connects with attitudes, as evaluations that drive our actions and, in some of these cases, our inactions. Attitudes are not only part of the news consumed worldwide, but are also a subject of general interest that has increased over time. For example, Amazon lists over 30,000 books containing the word attitude in the title, indicating the interest we have in understanding, and also changing, attitudes. Similarly, a search for the term attitude, on Google Scholar and PsycINFO, shows that the topic of attitudes has also continued to increase in popularity in the academic domain, resulting in a voluminous body of literature on the topic (see Figure 1.1).

The psychology of attitudes is generally a social psychology of attitudes. Clearly, cognitive psychology has contributed to our understanding of the microprocesses involved in attitude formation and change, and biological psychology can account for the sensorial mechanisms underlying preferences for certain objects, such as foods. There is, however, a reason why attitudes have been a focus in social psychology: Attitudes are often learned from others, make individuals similar to members of their groups, and are affected by social pressure and persuasion—the act of attempting to change the attitudes of another person. In this introductory chapter, we discuss these critical issues regarding the nature of attitudes, addressing classic and contemporary questions. In doing so, we give you insight into what the forthcoming chapters of the Handbook will cover in more extensive detail and, thus, provide a brief sketch of the general organization of this Handbook.

As shown in Figure 1.2, in this chapter, we consider attitudes in relation to beliefs, intentions, behaviors, and goals and also discuss the influence of various processes of attitude formation and change, including persuasive communications. This Handbook includes chapters on beliefs (Wyer, this volume); attitude structure (Fabrigar, MacDonald, & Wegener, this volume); communication and persuasion ( Johnson, Wolf, & Maio, this volume); the influence of attitude on behavior (Ajzen, Fishbein, Lohmann, & Albarracίn, this volume); motivational influences on attitudes (Earl & Hall, this volume); cognitive processes in attitudes (Wegener, Clark, & Petty, this volume); bodily influences on attitudes (Schwarz & Lee, this volume), neurofunctional influences on attitudes (Corlett & Marrouch, this volume); cultural influences on attitudes (Shavitt, this volume); and attitude measurement (Krosnick, Judd, & Wittenbrink, this volume). The second volume presents the many applications of attitude theory conducted within, and outside of, psychology, with chapters on cancer (Sweeny & Rankin); HIV (Glasman & Scott-Sheldon); dietary behavior (Mata, Dallacker, Vogel, & Hertwig); physical activity (Hagger); clinical contexts (Penner, Dovidio, Manning, Albrecht, & van Ryn); intergroup relations (Dovidio, Schellhaas, & Pearson); gender (Diekman & Glick); social class (Manza & Crowly); migrations (Esses, Hamilton, & Gaucher); accounting (Nolder & Kadous); and environmental behaviors (Milfont & Schultz).

Figure 1.1 Google Scholar and PsycINFO Searches for Attitudes Over Time, With the 2010s Only Through 2017

Figure 1.2 The Relation of Attitudes With Beliefs, Intentions, Behaviors, and Goals

Attitudes

The definition of an attitude needs to be one that is sufficiently comprehensive to cover the extent of current literature and generalizable to remain useful with evolving research trends (Eagly & Chaiken, 2007; Gawronski, 2007). What has been consistent in the multiple conceptualizations of the attitude construct is that evaluation is the key component (Ajzen, 2001; Albarracín, Zanna, Johnson, & Kumkale, 2005; Eagly & Chaiken, 1993; Gawronski, 2007; Maio & Haddock, 2009). Thus, in this chapter we define attitude as evaluation.

The target or subject matter of an attitude can be any entity, such as an object, a person, a group, or an abstract idea. Attitudes towards objects span many applications of social psychology, including such domains as marketing (e.g., attitudes towards products); advertising (e.g., attitudes towards ads); political behavior (e.g., attitudes towards political candidates, parties, or voting); and health (e.g., attitudes towards protective behaviors, new medications, or the health system). Attitudes towards a person or groups are often investigated under the umbrella of interpersonal liking and prejudice. Attitudes towards abstract ideas involve values, such as judging freedom or equality as desirable.

Attitudes also vary in terms of specificity versus generality. An attitude towards Donald Trump is specific in target (e.g., his hairdo comes to mind), but many attitudes are general. For example, some individuals hold relatively positive attitudes towards all objects, whereas others dislike most objects, people, and ideas (Hepler & Albarracín, 2013). Further, attitudes concerning an object can have different degrees of specificity with respect to temporal and spatial contexts (see Ajzen & Fishbein, 2005; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). For example, receiving the flu vaccine in the next month represents less commitment than consistently receiving the flu vaccine every fall. Likewise, receiving the flu vaccine in Chicago may seem more desirable than receiving the flu vaccine while vacationing in the South Pacific.

Measurement also has implications for distinctions among attitudes (see Krosnick et al., this volume). The development of attitude measurement techniques, for instance, has enabled researchers to measure attitudes indirectly rather than relying exclusively on explicit ratings of liking or approval (Bassili & Brown, 2005; Gawronski, 2007). These indirect measures of attitudes, referred to as implicit, are intended to assess automatic evaluations that are generally difficult to gauge using explicit self-reports (see Gawronski, this volume). For example, the effectiveness of implicit measures is implied by evidence showing that they are often inconsistent with (Petty, Fazio, & Briñol, 2009), and predict different outcomes from (Maio & Haddock, 2009), self-reported or explicit attitudes.

The divergence between implicit and explicit attitudes has commonly been seen as evidence suggesting that they measure two distinct representations of attitudes, namely, unconscious and conscious processes (Wilson, Lindsey, & Schooler, 2000). Alternatively, the lack of intercorrelation between implicit and explicit attitudes has been used to suggest that each measure captures upstream and downstream processes, specifically automatic responses and intentionally edited judgments related to the same attitude (Fazio, 1995; Nier, 2005). Some scholars have even questioned whether attitudes can be regarded as stable entities, or if they are instead constructed only when the attitude object is encountered (e.g., Schwarz, 2007). In an attempt to address this debate, Hofmann, Gawronski, Gschwendner, Le, and Schmitt (2005) conducted a meta-analysis of 126 studies examining the relation between implicit and explicit representations. In this synthesis, the correlation between the Implicit Association Test (IAT) and explicit attitude measures was r = .24 but varied as a function of psychological and methodological factors (Hofmann et al., 2005). For instance, the correlation between implicit and explicit measures varied as a function of the amount of cognitive effort used during explicit self-report tasks, suggesting different transformations of a single evaluative response.

Neuroimaging studies have observed similar differences between implicit and explicit attitudes (see Corlett & Marrouch, this volume). For example, the structures involved during automatic evaluations have been found to include the amygdala, the insula, and the orbitofrontal cortex (Cunningham, Johnson, Gatenby, Gore, & Banaji, 2003; Cunningham, Packer, Kesek, & van Bavel, 2009; Cunningham, Raye, & Johnson, 2004; Wright et al., 2008). In contrast, those involved during controlled evaluations have been found to include regions of the anterior cingulate cortex, including the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (Cunningham et al., 2003; Cunningham et al., 2004; Critchley, 2005). Together, these studies suggest that there may also be a neural distinction between the processes engaged during automatic and deliberate processing, which is compatible with the notion that implicit measures capture earlier, spontaneous, affective processes, whereas explicit attitudes reflect more deliberate adjustments on the basis of current goals or social desirability concerns.

Behavior, Beliefs, Intentions, and Goals

A few additional concepts central to the psychology of attitudes and persuasion include behavior, intentions, goals, and beliefs. Behavior is typically defined as the overt acts of an individual (Albarracín et al., 2005) and is generally assumed to partly stem from attitudes. Considerable research on the attitude-behavior relation indicates that attitudes are fairly good predictors of behaviors. For example, a meta-analytic review of the literature has found that the average correlation between attitudes and behavior is r = .52 (Glasman & Albarracίn, 2006) and that this association varies with a number of established moderators (see Ajzen et al., this volume).

An intention is a willingness to perform a behavior. Intentions often emerge from broader goals—desirable end states—that can be achieved via multiple, sustained behaviors; are not fully controllable results; and require external help or resources (Ajzen & Fishbein, 2005). For example, people develop intentions to increase physical activity with the goal of losing weight, but executing the intended behavior is no guarantee of success.

Like attitudes, goals can be specific or general. On the one hand, attitude-behavior researchers have generally studied fairly specific goals, such as the goal to quit smoking (see Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). When set, these goals are facilitated by intentions to perform specific actions, like throwing away smoking-related paraphernalia or avoiding friends who smoke. The intention to quit smoking or achieve a similar goal is an excellent predictor of actual behavior. For example, meta-analyses of specific health behaviors, such as condom use and exercise, have yielded average intention-behavior correlations ranging from .44 to .56 (Albarracín, Johnson, Fishbein, & Muellerleile, 2001; Godin & Kok, 1996; Hausenblas, Carron, & Mack, 1997; Sheeran & Orbell, 1998). On the other hand, traditional goal researchers have studied more general goals, such as the achievement motivation or the affiliation need (Elliot & Church, 1997; Maslow, 1970). These goals have a weak correspondence to specific behaviors, probably because they are carried out over long periods of time and across many domains. For example, achievement or affiliation motivations correspond to personality or stable patterns of behavior (for a recent review, see Moskowitz, Li, & Kirk, 2004) and can either be measured or manipulated with methods borrowed from cognitive psychology (e.g., presenting semantically linked words; see Hart & Albarracín, 2009; Weingarten et al., 2015). Perhaps the most general class of all investigated goals (see Albarracín et al., 2008; Albarracín, Hepler, & Tannenbaum, 2011) entails general action goals, which are generalized goals to engage in action (e.g., activated with instructions such as go), as well as general inaction goals, which are generalized goals not to engage in action (e.g., activated with instructions such as rest). These goals are diffuse desired ends that can mobilize the execution of more specific activities. Action goals imply a need to do irrespective of what one does; inaction goals imply a need to not do, irrespective of the domain. Hence, their activation may trigger the pursuit or interruption of any particular (overt or covert) behavior that is subjectively relevant to the goal.

A belief can be defined as a person’s subjective probability of a relation between the object of the belief and some other object, value, concept, or attribute and affects people’s understanding of themselves and their environments (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). A conceptualization proposed by McGuire (1960, 1981) and extended by Wyer and Goldberg (1970; see also Wyer, 1974) addressed how prior beliefs can influence new beliefs and attitudes. McGuire (1960) stated that two cognitions, A (antecedent) and C (conclusion), can relate to each other by means of a syllogism of the form A; if A, then C; C. This structure implies that the probability of C (e.g., an event is good) is a function of the beliefs in the premise or antecedent, and beliefs that if A is true and if A is true, C is true. Further, Wyer (1970; Wyer & Goldberg, 1970) argued that C might be true for reasons other than those included in these premises. That is, beliefs in these alternate reasons should also influence the probability of the conclusion (not A; if not A, then C). Hence, P(C) should be a function of the beliefs in these two mutually exclusive sets of premises, or:

| P(C) = P(A)P(C/A)+P(~A)P(C/~A), | [1] |

where P(A) and P(~A) [= 1 − P(A)] are beliefs that A is and is not true, respectively, and P(C/A) and P(C/~A) are conditional beliefs that C is true if A is and is not true, respectively.

A limitation of the conditional inference model described above is the use of a single premise. Although other criteria are considered, these criteria are lumped together in the value of P(C/~A), or the belief that the conclusion is true for reasons other than A. In contrast, other formulations consider multiple factors. Slovic and Lichtenstein (1971), for example, postulated that people who predict an unknown event from a set of cues are likely to combine these cues in an additive fashion. Therefore, regression procedures can be used to predict beliefs on the basis of the implications of several different pieces of information. In this case, the regression weights assigned to each piece provide an indication of its relative importance.

Multiple-regression approaches can be useful in identifying individual differences in the weights given to different types of cues (Wiggins, Hoffman, & Taber, 1969). Nevertheless, the assumptions that underlie these approaches are often incorrect (Anderson, 1971, 1981; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Wiggins &...