![]()

INTRODUCTION: LETTER 1

GETTING ACQUAINTED

Dear Teacher:

This book contains a series of letters I’ve written about how to expect, welcome, and support lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) students and families in school. I use the initialism LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and queer) to include people who identify as transgender, transsexual, Two-Spirit, questioning, intersex, asexual, pansexual, ally, agender, gender queer, gender variant, and/or pangender. If some of these words are unfamiliar to you, don’t worry. You will find an explanation of some of them in the letters that follow and a definition of all of them at the end of this book in “The Unicorn Glossary,” written by benjamin lee hicks.1

While I have just named some of the different ways people currently identify under the initials LGBTQ, I’ve learned that the ways people describe their gender and sexual identities are always evolving. This means the list I’ve put together for this book will change over time. I’ve also learned that, when I talk about people’s identities, I show respect by using the names and pronouns people use themselves. If I’m not sure how people identify, I’ve learned to ask.

In writing these letters, I have drawn upon the discussions I’ve had with students enrolled in a teacher education course on sexuality, gender, and schooling that has been taught at the Ontario Institute of Studies in Education (OISE) at the University of Toronto for 16 years.2 The course began in 2001 as a discussion group for teacher education students who identified as LGBTQ. The group talked about ways of dealing with homophobic slurs and name-calling at school, whether or not to come out as LGBTQ to colleagues and students, and how to include LGBTQ content into their classroom curriculum. The discussion group was our teacher education program’s Gay Straight Alliance (GSA) (if you’re not sure what a GSA is, see Letter 2).

After the group had successfully run for a year, my colleague Bob Phillips and I decided to turn the discussion group into an elective course, moving our sexuality education work from the margins of OISE’s teacher education programming to its centre. In January 2003 the course became the first and only 36-hour teacher education course in Canada to feature conversations about sexuality at school. When the course was first offered it focused on discussions of homophobia, heterosexism, and heteronormativity. More recently, it has also taken up discussions of gender expression, gender transition, and the socio-political factors that affect transgender and gender diverse students and families.

Moving from a short history of OISE’s course on sexuality, gender, and schooling to a description of the letters I’ve written, you’ll see that the book has been divided into three parts. Part 1 includes a set of letters about teaching sexuality at school; Part 2 contains a set of letters about gender at school; and Part 3 comprises letters about the experiences of LGBTQ families in school.3 But, before you read any further, I’d like to tell you a little about my past and current research, which has informed my thinking around teaching about gender and sexuality at school.

My First Research Study on Anti-Homophobia Education at School

My first research study on anti-homophobia education at school began in 2001. I wanted to find out how, if at all, principals and teachers working in four different schools at the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) had been able to implement their new anti-homophobia equity policy.4 I also wanted to find out in what ways, if any, had implementing the policy created tensions and conflicts for principals and teachers. The 18-month study ran from 2001–2003 and included one elementary school, one middle school, and two high schools. I worked with a research team of three students: doctoral student Susan Sturman, and undergraduate students Anthony Collins and Michael Halder. As a team we identified as cisgender and either lesbian or gay. Three of us identified as White and one of us as Pakistani. I identify as cisgender, lesbian, and White

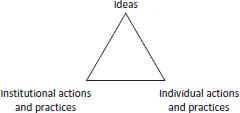

Using an analytic framework called the Triangle Model5 we found that teachers and principals who were trying to challenge homophobia in their schools needed to address homophobic ideas that circulated about LGBTQ people.

They also needed to address individual actions and practices of homophobia, such as name-calling and homophobic bullying. Finally, they needed to address institutional forms of homophobia; for example, school curriculum that completely excluded LGBTQ people. We also found that teachers and principals who had begun implementing anti-homophobia education were afraid that their school’s commitments to LGBTQ rights might collide with some of their parents’ religious beliefs about homosexuality, a topic I take up in Letters 4 and 5.6

When the study was completed I wanted to find a compelling way to share the findings with principals, teachers, students, and parents. So, I wrote a play script called Snakes and Ladders based on the major findings of the study that could be read aloud and discussed by teachers and principals in a class or at a conference. While the characters in the play are fictional, the conflicts featured in the play actually took place and were documented in the research.

Snakes and Ladders tells the story of what happens when a group of high-school teachers and students attempts to put on Pride Week at their school. Coalitions are built, homophobia is resisted and reproduced, and teachers and students learn that they can’t take their human rights for granted. Originally written in 2004, and updated and edited in 2010 for publication in the International Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy,7 the play is included at the end of this book, after “The Unicorn Glossary.” Several of the letters in Part 1, entitled Sexuality at School, discuss the findings of the research as they have been represented in particular scenes in Snakes and Ladders. After reading these letters you may be interested in reading and discussing the entire script with your colleagues and students. A list of discussion questions is included at the end of the play.

My Current Research on Gender and Sexuality at School

While my first research project focused on the anti-homophobia education work of four schools in the city of Toronto, my current research study involves interviewing between 35 and 40 LGBTQ families across the province of Ontario about their experiences at school. I’m also interested in how families work with teachers and principals to create safer and more supportive learning environments for their children. The six-year study, which we named LGBTQ Families Speak Out, began in 2014 and will end in 2020. I have worked on the study with five doctoral, one Master and four undergraduate students: Pam Baer, Austen Koecher, benjamin lee hicks, Jenny Salisbury, Kate Reid, Tarra Joshi, Katrina Cook, Alec Butler, Edil Ga’al, and Yasmin Owis. They each self-identify in the following ways: Pam Baer identifies as agender, queer, and White; Austen Koecher identifies as cisgender, White, and a child of a queer family; benjamin lee hicks identifies as genderqueer/trans, pansexual, and White; Jenny Salisbury identifies as a cis, straight, White woman of Dutch and Canadian settler heritage; Kate Reid identifies as queer and White; Tarra Joshi identifies as cisgender, South Asian/White; Katrina Cook identifies as a White woman and a child of a queer family; Alec Butler identifies as non-binary, intersex, Two-Spirit, Indigenous/settler; Edil Ga’al identifies as a Black woman; and Yasmin Owis identifies as a queer/bisexual, cisgender woman of colour. In Part 2, Gender at School, and Part 3, LGBTQ Families at School, I include excerpts from a number of the interviews and use the insights of the families to talk about a variety of experiences. In addition to reading what several of the families have to say, you can also view video clips from their interviews on our website: www.lgbtqfamiliesspeakout.ca.

Some of the names of the interviewees in this book are pseudonyms while others are not. Our team’s practice concerning the use of pseudonyms is to provide our participants with the opportunity to use a pseudonym when excerpts of their interviews are uploaded on to our website. Additionally they are able to choose to be anonymous by having their faces blurred and their voices changed. Our interview participants also have an opportunity to review their edited video interview excerpts before we upload them onto our website, and/or tell us if there is an excerpt that they would rather not appear on the website. If there is an excerpt they don’t want on the website, we don’t upload it. As well, if any of our participants change their mind about having their interview being available online, we remove it from the website.

However, when it comes to publishing the results of our research we encourage all our research participants to choose a pseudonym, because once someone’s name has been published alongside their words that person can never be made anonymous. For this reason many participants have taken up our suggestion to choose a pseudonym. In this book, I indicate someone’s name is a pseudonym by putting the word “pseudonym” in parentheses beside their name; for example, Violet Addley (pseudonym). Others have asked us to use their real names because they are engaged in LGBTQ advocacy and activism and feel their lives and identities are already public. Therefore, they want our writing about their experiences at school to be attributed to them without a pseudonym. Finally, we have interviewed several children in this project. When we publish findings associated with any of the children’s interviews, we only use pseudonyms.

Recently the research team has written a series of verbatim theatre scripts about the experiences of LGBTQ families in Ontario schools. The series is called Out at School. Unlike Snakes and Ladders, which features fictional characters who are involved in conflicts that were documented in my first sexuality and schooling research study, each script in the Out at School series is made up of a set of monologues that have been solely created from our interviewees’ own words. When we perform one of the scripts, the monologues are accompanied by a set of visual images created by team member benjamin lee hicks and original songs composed by team member Kate Reid. Out at School is a work in progress and will develop over the next few years. Our most current performance script appears with a list of discussion questions at the end of this book after Snakes and Ladders. The team follows the same practice of using pseudonyms in Out at School that we do in our other writing.

As you read through the letters in this book, you may experience a moment or two that unsettles you. Or you may experience a moment that pushes you to ask questions about what you know and what you don’t know. Some of the letters may provoke you to reassess a cherished teaching practice or belief. While working through unsettling questions can be uncomfortable, my students tell me that learning to ask questions about their beliefs and teaching practices has helped them become more accountable to LGBTQ students, parents, and colleagues. It helps them become the best teachers they can be. I hope this is your experience, too.

All the best,

Tara Goldstein

Toronto, July 2018

Notes

1 benjamin lee hicks has made an intentional choice not to capitalize their name.

2 Over the last 16 years, my colleagues Vanessa Russell, who is currently working as a teacher at the Toronto District School Board, and Heather Sykes, who teaches with me at OISE, have also taught the course. In the last several years OISE PhD students Pam Baer, Austen Koecher, and benjamin lee hicks have co-taught the course with me. The pedagogical ideas I discuss in these letters have been developed over the years in collaboration with Vanessa, Heather, Pam, Austen, and benjamin.

3 The book is called Teaching Gender and Sexuality at School because this is the way the field of gender and sexuality education has come to name itself (the word gender appears before the word sexuality). I begin with letters about teaching sexuality because that’s the way I began my own work. I started by teaching and researching the ways homophobia, heterosexism, and heteronormativity had an impact on people’s lives in school. More recently, I have engaged with the experiences of transgender and gender diverse children and youth at school.

4 The Toronto District School Board’s equity policy was approved in 1999 and published in 2000. However, many of the schools in the TDSB had been involved in equity education before the policy was approved. In January 1998 the Ontario government legislated forced amalgamation of the former Toronto Board of Education with five other Metro Toronto boards to create the TDSB. Each of these six school boards had its own equity policies, and work was needed to amalgamate them. The equity policy published in 2000 represents this amalgamation work. In 2000, the policy contained six sections. The first section presented the board’s Equity Foundation Statement. The other five sections presented the board’s five parallel commitments to equity policy implementation. There were commitments to (1) anti-racism and ethnocultural equity; (2) anti-sexism and gender equity; (3) anti-homophobia, sexual orientation and equity; (4) anti-classis...