![]()

Part I

Ionising Radiation Effects

![]()

1The Molecular Model and DNA Double Strand Breaks

A detailed, parameterised linear–quadratic dose–effect equation for the induction of DNA double strand breaks by ionising radiation is derived based on the known structure and properties of the DNA molecule in eukaryotic cells. Experimental measurements of the dose–effect relationships for the induction of DNA double strand breaks are presented, in support of the linear–quadratic dose–effect equation. The inferences, implications and insights for radiation action which can be drawn from a consideration of the detailed linear–quadratic equations are elaborated.

1.1 The Molecular Model Hypothesis – the Basic Concepts

The molecular model used to provide a qualitative and quantitative description of ionising radiation effects in cells is based on just two postulates:

- 1. The DNA double strand break is the crucial cellular lesion which may lead to cell inactivation, chromosomal aberrations and mutations.

- 2. The dose–effect relationship for the induction of DNA double strand breaks is linear–quadratic.

Everything else derives directly from these two postulates as straightforward consequences which depend on the structure and properties of the DNA molecule, on the chemical surroundings of the DNA, and on the track structure and properties of the different radiations.

A third postulate is:

- 3. The radiation effects induced in cells lead to the various radiation-induced health effects.

The first postulate, that the double strand break is a critical lesion for a cell, is not contentious and is generally accepted, but there are two major objections to the model. One, which can be called the ‘micro-dosimetry problem’, concerns the probability that two independently induced DNA single strand breaks will be close enough to create a double strand break at radiation doses relevant for the biological effects. The other objection, which can be called the ‘cytological problem’, concerns the production of chromosome exchange aberrations from a single DNA double strand break. These two objections will be addressed at the appropriate stages as the development of the model is expanded through the book.

In this first chapter, a detailed, parameterised linear–quadratic dose–effect equation for the induction of DNA double strand breaks by ionising radiation is derived using the known structure and properties of the DNA molecule in eukaryotic cells. Experimental measurements of the dose–effect relationships for the induction of DNA double strand breaks are presented confirming the linear–quadratic dose–effect equation. The equation is then used in Chapter 2 to develop dose–effect relationships linking the number of double strand breaks to three cellular effects: cell death, the yield of chromosomal aberrations and mutation frequency.

1.2 The Induction of DNA Double Strand Breaks

There are good reasons for choosing deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) as the important target for radiation effects. DNA is common to all living cells and provides the universal genetic code. It has a high molecular weight and forms the backbone of the chromosomes which are contained in the nucleus of the cell. The DNA in a cell controls the internal working and defines the specific activity of the cell in an organism. Any disruption of the mechanical or genetic integrity of the DNA molecule will clearly have serious consequences for the continued normal function of a cell.

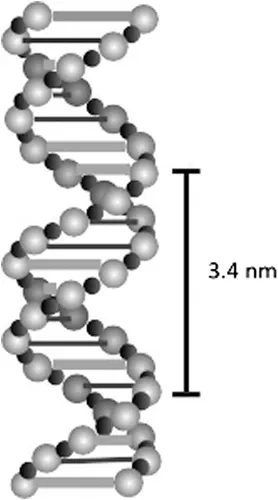

The DNA molecule has a well-defined three-dimensional structure originally determined by Watson and Crick in 1953 (Watson and Crick 1953). Two long polymer chains of alternating sugar and phosphate units are wound around each other in the form of a double helix. The two sugar-phosphate polymer chains are linked at each sugar unit by one of two purine–pyrimidine pairs of nucleotide bases, adenine–thymine pairs (A–T) and guanine–cytosine pairs (G–C), and, because the dimension of the A–T pair is the same as the dimension of the G–C pair, the two sugar-phosphate chains are held parallel to each other, separated by 1.2 nm, so that the structure resembles a long, twisted, lightly coiled, rope ladder on a molecular scale. The two sugar-phosphate strands are wound round each other to make one full turn every 3.4 nm in a right-handed spiral, which in turn is wound around a central axis so that a major groove and a minor groove are formed. Each complete unit of base plus sugar plus phosphate is called a nucleotide so that each strand of the DNA is a polynucleotide chain. The nucleotide purine–pyrimidine pairing occurs every 0.34 nm along the sugar-phosphate chain so that there are ten links holding the chain together for every full turn of the spiral. The sequence of the purine (A, G) and pyrimidine (C, T) bases along the chain forms the basis of the genetic code. The result, illustrated in Figure 1.1, is a very long, thin molecule reaching up to 50 mm in length with a diameter of 2 nm.

FIGURE 1.1 A schematic representation of the DNA double helix molecule.

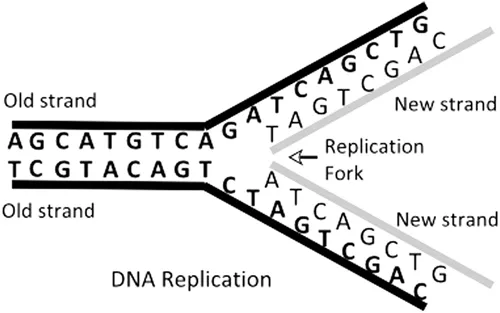

In addition to providing the basis of the genetic code, the complementary base pairing makes it possible for the DNA molecule to replicate itself correctly during the DNA synthesis (S) phase of the cell cycle. In DNA synthesis, the two ‘old’ strands of DNA loosen and replication starts at many replication origins, proceeding in both directions along the DNA (Benbow et al. 1985; Linskens and Huberman 1990; Douglas et al. 2018). The ‘old’ strands are copied to make two ‘new’ strands with complementary base pairing so that the two new double helices are exact copies of the original double helix and each of the two helices has one ‘old’ strand and one ‘new’ strand (see Figure 1.2). At mitosis, the two new DNA double helices separate into two daughter cells, each of which carries the same genetic information from the original cell.

FIGURE 1.2 A schematic diagram of the process of the replication of DNA.

1.3 The Linear–Quadratic Function and DNA Double Strand Breaks

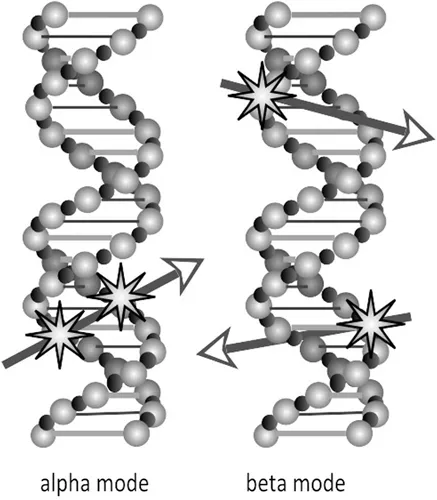

It is not difficult to understand how a linear–quadratic dose–effect relationship for the induction of double strand breaks, which obviously disrupt the integrity of the DNA double helix molecule, can be derived from the interaction of radiation tracks with the molecular structure presented in Figure 1.1. A double strand break can be induced as a consequence of one ionising radiation track breaking both strands of the DNA double helix, giving a yield of breaks in proportion with radiation dose (αD). A DNA double strand break can, at least hypothetically, also result as a consequence of the close spatial proximity of two independently induced single strand breaks, giving a yield of double strand breaks in proportion with the square of the radiation dose (βD2), as is illustrated in Figure 1.3.

FIGURE 1.3 Schematic representation of the hypothetically possible formation of DNA double strand breaks in two different modes of radiation action.

In accordance with these two modes of radiation action, the average number (N) of DNA double strand breaks per cell induced by a dose (D) of radiation is, in general, given by the equation:

Figure 1.4 presents the number (N) of double strand breaks as a function of dose (D) according to the linear–quadratic Equation 1.1, broken down into its two components to show that the (α) coefficient represents the initial linear slope of the curve from zero dose, and the (β) coefficient accounts for the...