![]()

Chapter 1

What is motor control?

| Key Notes |

| Motor behavior | Any voluntary action or movement to achieve a goal. |

| Motor control | Ability to maintain and change posture and movement in a variety of contexts. |

| Motor development | The process of change that a person passes through starting from birth. |

| Motor skill | Ability to reliably and consistently achieve a goal through learned movement. |

| Motor learning | A relatively permanent change in behavior as a result of practice or experience. |

| Related topics | Classification of skill (2) | Measurement in motor control (3) |

In our daily lives we all produce a whole host of movements that are crucial to our independence, interactions with the world, personal safety and at times rehabilitation (Muratori et al. 2013). Motor control is the study of movements, the mechanisms that enable movements to be produced and the processes that underlie control, skill acquisition and retention. When studying motor control we are asking questions about what needs to be controlled, how we learn to do this, and how we are able to coordinate the vast range of simple and complex movements that we perform. The term motor control also reflects a multidisciplinary approach to asking and answering questions about control. Knowledge of motor control and motor learning should form a fundamental part of any individual’s theoretical background who is involved in sport, physical activity and rehabilitation (Newell and Verhoeven 2017). Equally, an understanding of motor development is crucial if you are involved in teaching coaching or planning interventions that involve movement. This section provides an overview of the field of motor control, defines the terms used and considers why we need to study motor control, learning and development.

Definition of terms

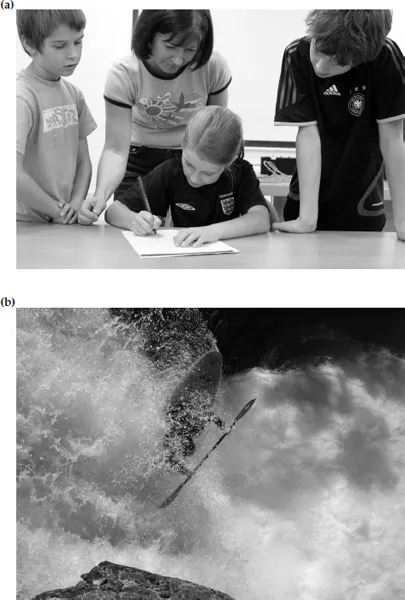

It is through movement that we interact with the world either by moving around in different contexts or handling objects, or by dealing with other people (Figure 1.1). In order to do this we have to control a mass of different movements that vary in complexity and speed while dealing with multiple or related inputs. A range of terms is used to define movement, and as a starting point to the remainder of this book, it is important that these are clearly defined. We have used the term motor control as a starting point; however, the term motor behavior is often used (see Chapter 2 for further definitions). Many researchers use the term motor behavior to describe any motor action or movement that is used to complete a task or achieve a goal. The study of motor behavior is then divided into three areas: motor control, motor learning and motor development. It is useful to understand the distinction between these areas.

Motor control

The starting point in defining motor control is to remember that it is the study of the nature and cause of movements or actions. When studying motor control we are studying postures and movements and the mechanisms that enable us to move. There are three key aspects to motor control that have to be taken into account. First, motor control is concerned with the study of action. When we examine motor control, we often consider a particular action such as running, catching or picking up an object. However, it must be remembered that an important part of movement is the interaction between the environment and the individual. Second, as we move, we use sensory information about our position in the environment and the position of our body in relation to the environment and other body parts. Motor control is therefore also concerned with the study of perception. Finally, we must also remember that movement involves cognitive processes in order to organize perception and action. Therefore motor control is also concerned with the study of cognition and, within this, motor planning, which refers to the processes related to preparation for movement. Wong et al. (2015) suggest a definition of motor planning that encompasses only those processes necessary for a movement to be executed and only processes that are strictly movement related.

Figure 1.1 In our daily lives we produce a whole host of movements such as writing, sitting, standing, (a) more complex movements such as whitewater kayaking (b) and complex movements that involve multiple factors such as soccer (c).

Another feature of the study of motor control is the formation of theories, the testing of theories, and the use of models to understand movement. A theory of motor control is a group of abstract ideas about the nature and the cause of movement. A model is a representation of something, usually a simplified version of the real thing. The better the model, the better it will predict how the real thing will behave in a real situation. Throughout this book, we will consider theories and models of control in order to critically assess human motor control.

Motor learning

Motor learning is an area that has received a mass of attention from a range of researchers who are interested in examining how we learn and retain movement skills. Learning is defined as a change in a person’s capability to perform a skill. Wolpert et al. (2001) state that learning involves a change in behavior that occurs as a result of interaction with the environment that is distinct from maturation. It must be remembered that this is inferred from a relatively permanent improvement in performance as a result of practice or experience. Two terms that should not be confused are learning and performance (see Chapter 2). Performance is observable; you can see a footballer take a penalty or watch a climber tackle a rock face. Learning, however, cannot be directly observed and can only be inferred from the nature of the movement produced (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Performance is observable; you can watch a climber complete a route, for example.

Motor development

Motor development refers to the process of change that a person passes through as they grow and mature. Development, according to Keogh and Sugden (1985, p. 6), is an ‘adaptive change towards competence’. The human adult is capable of performing a variety of motor skills and demonstrates a high level of control and dexterity. The development of motor control is complex and involves the development of many behaviors (see Chapter 14). Motor development in children is so rapid and so apparent that we sometimes forget that motor development is a lifelong process – learning to walk for example. During the development of motor control, children are establishing the movement patterns and control synergies that will be used throughout life. This development has implications when studying how movements are coordinated and how this is influenced by task constraints and the environmental context.

Origins of the field

The field of motor control emerged from two separate fields of study: neurophysiology and psychology. These fields developed separately, and it was only in the 1970s that they came together and motor control became an area of study. Many of the early studies examined tasks such as hand movements (Bowditch and Southard 1882) and learning tasks such as typing and Morse code (Bryan and Harter 1899; Hill et al. 1913). Bryan and Harter’s (1899) first formal study of skill acquisition looked at the way people learn to communicate with Morse code. They noted that:

- learning is discontinuous in nature (plateaus)

- we tend to learn small units and combine these into larger units, then even larger units (chunking).

The second point is still largely credible today. It was Woodworth (1899), however, who was the first to attempt to fully understand motor skills by comparing fast and slow movements. He asked subjects to move a pencil back and forth through a slit, with the direction reversing once two marks had been passed. The rate of moving the pencil was controlled by a metronome, and subjects performed one set with their eyes open and another set with their eyes closed. He discovered that when subjects had their eyes closed, the mean absolute error remained more or less constant as velocity decreased. When subjects had their eyes open, the mean absolute error decreased as velocity decreased. Therefore, accuracy improved as movements slowed in the eyes-open condition but not in the eyes-closed condition. Woodworth concluded that in the eyes-closed condition, subjects’ movements were entirely preprogrammed; he referred to this as an initial impulse. In the eyes-open condition, he concluded that the movements were both preprogrammed and corrected with current control (visual feedback).

What is interesting to note is that many of these early studies were concerned with improving human performance in the workplace or in connection with the work of the military. The next part of this section outlines some of the landmark studies from the early work to that conducted in the last few years.

Key players and motor control landmarks

The work of Woodworth (1899) has already been covered, but a number of other studies have been conducted that have formed the basic foundation of research in the area of motor control. A number of the key researchers and their studies are reviewed here in chronological order.

Charles Sherrington

Work on reflexes and sensory receptors by Sherrington (1906) formed the foundation of a number of major concepts in motor control. He was the first to conduct studies on sensory receptors and he was the first to use the term proprioception.

Edward Thorndike

Thorndike (1914) was interested in learning and he developed the term ‘law of effect’, which basically states that responses that are rewarded tend to b...