![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Crime scene processing is an inherent task and duty associated with most criminal investigations, for rarely does one encounter a crime without some kind of crime scene. Crime scene processing consists of an examination and evaluation of the scene for the express purpose of recovering physical evidence and documenting the scene’s condition in situ, or as found. The end goal of crime scene processing is the collection of the evidence and scene context in as pristine a condition as possible. To accomplish this, the crime scene technician engages in six basic steps: assessing, observing, documenting, searching, collecting, and analyzing. These steps, and the order in which they are accomplished, are neither arbitrary nor random. Each serves an underlying purpose in capturing scene context and recovering evidence without degrading the value of either. However you look at it, this is not an easy task, since the mere act of processing the scene disturbs the scene and evidence. Yet, from these efforts, the crime scene investigator (CSI) will walk away with important items of physical evidence and scene documentation in the form of sketches, photographs, notes, and reports. All this information plays a significant role in resolving crime by providing objective data on which the investigating team can test investigative theories, corroborate or refute testimonial evidence, and ultimately demonstrate to the court the conditions and circumstances defined by the scene. This is a task that is easily said, but it is not so easily done.

Action without purpose is folly and, simply put, becomes wasted effort. This is true in any endeavor. Therefore, it is imperative that before pursuing the actions a CSI conducts at the scene, they must understand their mandate. Crime scene processing is a duty in every sense of the word. Crime scene processing is not something the technicians do because “they were told to,” but rather because they have a responsibility to do so. If the CSI fails to recognize this duty and its ultimate purpose, many of the procedures used at the scene might appear meaningless and therefore, unnecessary. But each has an underlying purpose in seeking to recover both evidence and scene context. What follows in this chapter is a discussion of the conceptual and theoretical ideas behind crime scene processing. As we will discover, there is no single “right way” for crime scene technicians to conduct themselves at a scene, but there are certainly a number of wrong ways.

No matter what action a CSI takes, ultimately, he or she will be asked to defend that action in court. Opposite the CSI will be a counsel with little, if any, understanding of the process or practice of crime scene investigation. What the counsel is likely to have, however, are excerpts from various references on crime scene investigation, with no contextual understanding of what they mean. To stand the test of cross-examination and not allow a counsel to misrepresent these references, the CSI must be able to articulate the reasons why a certain action was taken over some other course of action. Without this ability, the counsel will likely sway the jury that the police failed in their duty. So, it is not enough that a CSI can process the scene, he or she must understand the underlying theory to weather such storms in court.

Even before we can speak to the conceptual issues of crime scene processing, we must ask and answer an even more basic question. Why does this duty to society exist? What is the true function of the police and the investigator in a free society? Many will say, “It is to see that justice is done.” The police are clearly a significant player in society’s efforts to seek justice. Yet, the police are only one player in a convoluted criminal justice system, and unfortunately the search for justice in that system is oftentimes confusing. Despite the confusion of the system, the role of the professional police and the CSI is really quite clear.

Police Goals and Objectives

The true role of the police, and thus the CSI, is very well defined with little, if any, ambiguity. In a free society, the police have two basic goals:

1. The prevention of crime and disorder, and the preservation of peace

2. The protection of life, property, and personal liberty

This mandate ultimately defines why police act as they do and why the role of the CSI is so important to the criminal justice system. To achieve these two goals, the police apply five basic objectives:

1.Crime prevention: Prevention includes the actions and efforts designed to keep crime from occurring in the first place. Crime is not singularly a police problem; it is a societal problem. Community programs, youth programs, proactive patrol techniques, and participation in neighborhood watches are all actions directed toward preventing crime from occurring.

2.Crime repression: When prevention fails, the police seek to repress the criminal by actively investigating crimes and attempting to identify those responsible. A criminal investigation is clearly rooted in our crime repression activities. If the police fail to stop a crime, they must investigate the crime fully and impartially and, if possible, identify those whom they believe are responsible. Once identified, the police are then responsible for apprehending the criminals and bringing them to justice.

3.Regulating noncriminal conduct: The police act to control general behavior patterns, such as compliance with city ordinances and traffic regulations, in order to prevent chaos.

4.Provision of services: As any police officer knows, when there is no one else to call, a citizen will call the police. From helping stranded motorists to looking for lost children, the scope and breadth of the services provided by police is very broad.

5.Protection of personal liberty: This is perhaps the single most confusing aspect of the police role in society. Police have a mandate to protect citizens from unwarranted police interference of their personal liberties. In effect, the police must actively control their own behavior to ensure that their methods and practices abide by the Constitution and the law.

Crime repression and protection of personal liberty are both related to the criminal investigation and the processing of the crime scene, and thus they are important objectives. The police must proactively investigate the crimes reported to them and do so in a manner that is consistent and respectful of the law and the liberties of those they encounter. Even with these objectives in mind, significant confusion still arises in this mandate, and it relates specifically to concepts of duty, truth, and justice.

When presented with grotesque and unimaginable crimes, those responsible for the investigation almost always feel an extreme sense of urgency and, oftentimes, a very personal sense of duty to resolve the investigation. Ego or pride, disgust with the kind of human that would act so inhumanely, or empathy for the victims themselves can build stress that few outside of the profession will understand or even recognize. Unfortunately, over-personalization of the event in any investigator’s mind can also warp his or her sense of duty. Always remember that the true duty is to remain professional and objective and through this foundation of professionalism resolve the investigation. Without objectivity, police end up acting on emotion and that can lead to a subjective nightmare.

As for our beliefs on truth and justice, the two words are often bandied about as if they were somehow synonymous. Truth is simple fact, without regard to agenda and subjective factors. Truth is the old Joe Friday routine: “The facts, ma’am, just the facts.” The suspect was last seen with the victim. This is Smith’s fingerprint. The victim’s deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is on the clothes of the subject. These are all examples of facts. These facts, alone, and considered out of context, rarely define an absolute truth about crime. It is through consideration of the totality of these facts that the investigator can draw some ultimate conclusion.

Justice, however, is different and a bit more complex. Justice is the process by which “each receives his due.” It is society, in the form of judges and juries, who defines justice. They do so using facts and evidence, but as most police officers know, the jury is not always privy to every piece of information. Whether it is because the police failed to collect it legally, or because some prosecutor does not want to “confuse” the jury, the jury acts based only on the knowledge and information presented to them. Also, it is important to understand that to be fair, justice considers the needs of three different entities: the victim, society, and the accused. Thus, for all these reasons, the course of events suggested by justice may well conflict with those suggested by the pure truth! This presents an interesting and oftentimes perplexing problem to the investigator. It becomes distracting to try and understand why the justice system acts as it does, particularly considering all of the information the investigator may know. All these distractions can lead to disillusionment and create significant ethical issues.

Nevertheless, the purpose of the criminal investigation remains first and foremost a search for truth, even if the investigator does not always understand, or in all cases agree with, the administration of “justice.” The bottom line is that the police seek to objectively define what happened and who was involved, and to do so in a manner that is lawful and does not violate the rights or liberties of those being investigated. Furthermore, the police are expected to seek this truth as objectively as possible, without regard to any personal agenda. As professional investigators, we have as much of a duty to refute an allegation as we do to try and corroborate it. Our master then is the truth and only the truth. Professional ethics demands an absolute adherence to this mandate.

There will certainly be moments when an investigator will be dismayed by what society thinks “justice” is, but the investigator must always remain cognizant of his or her specific role in seeking justice. Investigators are not, nor have they ever been, the judge or jury. When the police begin to view themselves as such, the result is something that can only be characterized as a police state, far from our concepts of democracy. The police must do their job as intended. If they seek and bring precise and objective information from the crime scene to the justice system, and if they do so without any agenda beyond seeking the truth, then the probability increases that true justice will be served.

Case Example: Facts vs.Agenda

In the late evening hours on a rainy December evening, a sheriff-elect returned home to join his family. He was going to be sworn in as the sheriff of a major metropolitan county within days. He parked his car on a cul-de-sac, as there were two vehicles of friends and relatives already in his driveway. He began walking east to the residence with several bags. His son observed this approach from the residence. He reported that as his father arrived at a point adjacent to the opening between the two cars in the driveway, the sheriff looked in a direction away from the driveway (to the northwest) and then turned in the same direction. The son reported hearing several gunshots, but he saw no one in between the cars while making his observations. The son ran for his father’s weapon and observed nothing further.

At that moment a neighbor, in the house immediately north of the victim’s home, was looking out her window. She observed a man dressed in black moving from the north side of the sheriff’s lawn to the south (toward the sheriff’s walkway and driveway). Her line of sight prevented direct observation of the vehicles and the driveway, but she did hear multiple gunshots and observed a single individual dressed in black run to the street. There he got into the passenger door of a small two-door sedan, which drove off. She provided specific information regarding characteristics of this vehicle.

When the shooting stopped, the family rushed from the residence to find the sheriff on the south side and at the east end of the driveway, close to the house. The sheriff-elect died of multiple gunshot wounds.

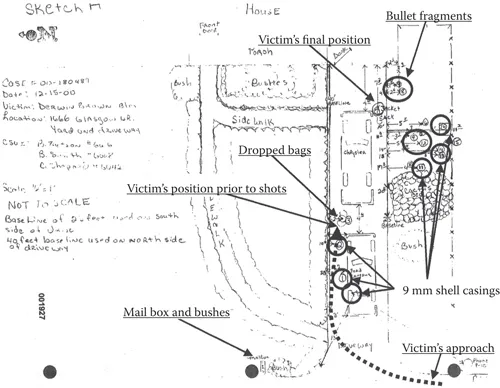

A crime scene examination was completed and significant evidence located. (See Figure 1.1.) Around the car that was closest to the street, police found three 9-mm cartridge cases. The first was beneath the vehicle by the left rear tire. The next was found on the north side of the vehicle, adjacent to the driver’s door, and the third was located on the north side, adjacent to the front left tire. Between the two cars in the driveway were the three bags the sheriff was carrying as he approached the house. Six more 9-mm cartridge cases were located in and around the grass at the south edge of the property. No cartridge cases were located east of the second vehicle in the driveway or to the east beyond the final location of the victim. The sheriff collapsed at the southeast corner of this vehicle. Three-feet east of his position, two bullet fragments were located in the grass.

Figure 1.1 The crime scene sketch depicts the location of shell casings and the victim’s position as observed by his son. The dropped articles support this positioning. The cluster of 9-mm casings on the north side of the car in the driveway speaks clearly to the position of the shooter at the initiation of this assault. This is in clear contradiction to the story provided by the co-conspirator. (Figure courtesy of Steel Law Firm, P.C.)

Of interest as the investigation developed, the mailbox was located to the west of the residence on the north side of the driveway and sidewalk, and it was surrounded by large bushes that would provide concealment from observation of anyone approaching from the street.

Forensic analysis of the cartridge cases indicated that the weapon used was a Tek-9 or similar weapon and that only one weapon had deposited all of the cartridge cases in the scene.

The case remained unsolved, with significant media attention and open speculation focusing on the outgoing sheriff as a possible suspect. A year after the event, a suspect was arrested in another homicide. The suspect was an ex-deputy with close ties to the outgoing sheriff, who was rumored to be behind the killing. The district attorney (DA) offered this suspect a deal to turn state’s evidence in the sheriff-elect’s murder, with one significant stipulation. The suspect could not be the primary shooter. With that exception, the suspect would serve one year on all charges, including the subsequent hom...