eBook - ePub

Prediction and Change of Health Behavior

Applying the Reasoned Action Approach

- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Prediction and Change of Health Behavior

Applying the Reasoned Action Approach

About this book

This book is based on a symposium held in honor of Martin Fishbein's 70th birthday in March 2006 at the Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania. The book's chapters are organized around two broad themes that reflect Marty's major research interests: Attitudes and Behavior and Health Promotion. Marty first started to work on a theory of attitudes while pursuing his dissertation research at UCLA.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Prediction and Change of Health Behavior by Icek Ajzen, Dolores Albarracin, Robert Hornik, Icek Ajzen,Dolores Albarracin,Robert Hornik in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Public Health, Administration & Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedicinePart 1

Attitudes and Behavior

Chapter 1

Predicting and Changing Behavior: A Reasoned Action Approach

University of Massachusetts

University of Florida

If you were told of a miraculous potion that could prevent all manner of illness— from cancer to cardiovascular disease, AIDS to malaria, diabetes to Alzheimer’s—you would be justifiably skeptical. And if, after reviewing the evidence, you found that the medicine had no more curative effects than a placebo, you would reject the claim and return to a more realistic search for the diverse causes and cures of these illnesses. Psychological research, by comparison, seems at times to obey a different set of rules. Our attempts to predict and explain human behavior tend to rely on broad dispositional constructs: locus of control, sensation seeking, trust in doctors, self-consciousness, liberalism-conservatism, dominance, hedonism, prejudice, self-esteem, authoritarianism, altruism, achievement motivation, and so on ad infinitum. The oft documented failure of such constructs to predict behavior has done little to undermine confidence in their utility.

Self-esteem is a good case in point. Low self-esteem is often considered a major cause of problem behavior. In 1994, Robyn Dawes (1994) wrote a scathing critique of a report (Mecca, Smelser, & Vasconcellos, 1989) by a task force on self-esteem and social responsibility established by the California State Assembly. In their report, the task force reviewed the voluminous literature on selfesteem and found virtually no evidence for any effects of self-esteem on child maltreatment, academic achievement, unwanted teenage pregnancy, crime and violence, chronic welfare dependency, or alcoholism and drug use. Nevertheless, the contributors clung to their preconceived ideas regarding the importance of self-esteem and suggested that interventions to increase self-esteem be encouraged. A more recent review of the literature (Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, 2003) again documented the lack of evidence for a relation between self-esteem and problem behavior among adolescents: “Most studies on self-esteem and smoking have failed to find any significant relationship, even with very large samples and the correspondingly high statistical power… Large, longitudinal investigations have tended to yield no relationship between self-esteem and either drinking in general or heavy, problem drinking in particular. Self-esteem does not appear to prevent early sexual activity or teen pregnancy” (p. 35). We do not wish to claim, of course, that self-esteem is a useless construct. All else equal, we might well prefer that people feel good about themselves, but it is important to recognize that this construct does little to advance our understanding of the determinants of human social behavior.

Other instances of injudicious reliance on dispositional constructs abound. For example, not much more encouraging than the findings regarding self-esteem are the results of research on racial prejudice and discriminatory behavior. In two recent meta-analyses (Schütz & Six, 1996; Talaska, Fiske, & Chaiken, 2004) of the relevant literature, the average correlations between measures of prejudice and discrimination were .29 (based on 46 data sets) and .26 (based on 136 data sets), respectively. Correlations of comparable magnitude were reported in recent research that, instead of measuring attitudes explicitly, obtained implicit measures by means of the Implicit Association Test (Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998) or evaluative priming (Fazio, Jackson, Dunton, & Williams, 1995). Like explicit measures of prejudice, implicit measures tend to have relatively low correlations even with nonverbal behaviors that are not consciously monitored (for reviews, see Ajzen & Fishbein, 2005; Fazio & Olson, 2003). Nevertheless, there is no readily apparent diminution in work on this construct. Again, we do not wish to give the impression that racial, ethnic, and gender prejudices are unimportant, but we have to realize that prejudice does not account for a great deal of variance in any particular behavior.

The Reasoned Action Approach

Evidence of this kind led Fishbein (1967a; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1972, 1975) more than 30 years ago to question reliance on global dispositions. Instead of studying the role of self-esteem, prejudice, internal-external locus of control, or some other global disposition, he suggested that we direct our attention to the particular behavior of interest and try to identify its determinants. Much prior theory and research had focused on one or another global disposition that might serve as an overarching causal agent and then tried to rely on this disposition to account for many different types of behavior in the disposition’s domain of application. By contrast, Fishbein and Ajzen proposed that we identify a particular behavior and then look for antecedents that can help to predict and explain the behavior of interest, and thus potentially provide a basis for interventions designed to modify it.

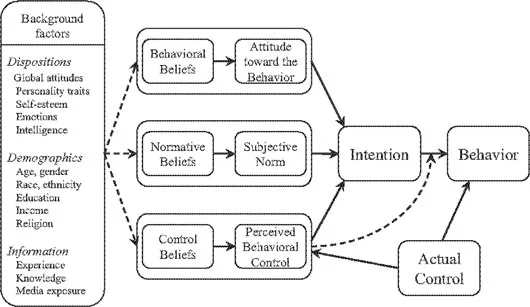

Of course, this quest would be quite unrealistic if we had to assume that each behavior is determined by a unique set of antecedents. The reasoned action model that emerged in response to the challenge, now known as the theory of planned behavior, actually identified a small set of causal factors that should permit explanation and prediction of most human social behaviors. Briefly, according to the theory, a central determinant of behavior is the individual’s intention to perform the behavior in question. As they formulate their intentions, people are assumed to take into account three conceptually independent types of considerations. The first are readily accessible or salient beliefs about the likely consequences of a contemplated course of action, beliefs which, in their aggregate, result in a favorable or unfavorable attitude toward the behavior. A second type of consideration has to do with the perceived normative expectations of relevant referent groups or individuals. Such salient normative beliefs lead to the formation of a subjective norm—the perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform the behavior. Finally, people are assumed to take into account factors that may further or hinder their ability to perform the behavior, and these salient control beliefs lead to the formation of perceived behavioral control, which refers to the perceived capability of performing the behavior. As a general rule, the more favorable the attitude and subjective norm with respect to a behavior, and the greater the perceived behavioral control, the stronger should be an individual’s intention to perform the behavior under consideration. Finally, given a sufficient degree of actual control over the behavior, people are expected to carry out their intentions when the opportunity arises. Intention is thus assumed to be the immediate antecedent of behavior. However, because many behaviors pose difficulties of execution that may limit volitional control, it is useful to consider perceived behavioral control in addition to intention. To the extent that perceived behavioral control is veridical, it can serve as a proxy for actual control and contribute to the prediction of the behavior in question. A schematic representation of the theory is shown in Figure 1–1.

Figure 1–1. The Theory of Planned Behavior.

Expectancy-Value Model

The three major determinants in the theory of planned behavior—attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceptions of behavioral control—are traced to corresponding sets of behavior-related beliefs. The relation between beliefs and overall evaluative attitude is embodied in the most popular model of attitude formation and structure, the expectancy-value model (see Feather, 1959, 1982). One of the first and most complete statements of the model can be found in Fishbein’s (1963; 1967b) summation theory of attitude. In this theory, people’s evaluations of, or attitudes toward, an object are determined by their salient or readily accessible beliefs about the object, where a belief is defined as the subjective probability that the object has a certain attribute (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). The terms object and attribute are used in the generic sense and they refer to any discriminable aspect of an individual’s world. When applied to attitudes toward a behavior, the object of interest is a particular action and the attributes are the action’s anticipated outcomes. For example, a person may believe that physical exercise (the attitude object) reduces the risk of heart disease (the attribute).

Each belief thus associates a behavior with a certain outcome. According to the expectancy-value model, a person’s overall attitude toward performing a behavior is determined by the subjective values or evaluations of the outcomes associated with the behavior and by the strength of these associations. Specifically, the evaluation of each outcome contributes to the attitude in direct proportion to the person’s subjective probability that the behavior will lead to the outcome in question. The basic structure of the model is shown in the equation below, where AB is the attitude toward the behavior, bi is the strength of the belief that the behavior will lead to outcome i, e is the evaluation of outcome i, and the sum is over all salient outcomes (see Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975).

A similar logic applies to the relation between normative beliefs and subjective norm, and the relation between control beliefs and perceived behavioral control. Normative beliefs refer to the perceived behavioral expectations of important referent individuals or groups such as the person’s family, friends, coworkers, and health professionals. These normative beliefs—in combination with the motivation to comply with the different referents—determine the prevailing subjective norm regarding the behavior. Finally, control beliefs have to do with the perceived presence of factors that can facilitate or impede performance of a behavior. It is assumed that the perceived power of each control factor to impede or facilitate performing the behavior contributes to perceived control in direct proportion to the person’s subjective probability that the control factor is present.

Basically, then, the theory assumes that human social behavior follows reasonably from the information or beliefs people possess about the behavior under consideration. These beliefs originate in a variety of sources: personal experiences, formal education, radio, newspapers, TV, the Internet and other media, interactions with family and friends, and so forth. No matter how beliefs were acquired, they are assumed to produce attitudes, subjective norms, and perceptions of control with regard to the behavior, and thus guide the formation of behavioral intentions and actual performance of the behavior.

To summarize briefly, Fishbein and Ajzen’s response to the failure of global dispositions, and in particular of global attitudes, to predict behavior was twofold. First, they suggested that we shift focus from global dispositions, such as attitudes toward broad objects, groups, institutions, or policies to behavior-specific dispositions, such as intentions to perform the behavior, attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms regarding the behavior, and perceptions of control over performing the behavior. This shift constituted a revolution in the theorizing of social scientists who for decades had relied almost exclusively on global dispositions in their attempts to explain social behavior. In fact, Fishbein and Ajzen’s insight has yet to reach many investigators as is evidenced by the continuing reliance on global dispositions in diverse areas of research. Second, Fishbein and Ajzen proposed that we apply the well-established expectancy-value model of general attitudes to the study of attitudes toward a behavior and that we extend its logic to the other antecedents of intentions as well. This approach is reminiscent of behavioral decision theory and its dominant theoretical framework, the subjective expected utility model (see Edwards, 1954). Both models focus on specific behavioral options and assume that an option’s perceived attributes determine a person’s decision. However, the expectancy-value model makes fewer psychometric assumptions, is more descriptive of the decision-making process, and is consistent with work on the psychological limitations of human judgments and decisions (see Ajzen, 1996). We return to this last point in the following discussion of misconceptions about the reasoned action approach.

Background Factors

Though focusing on determinants closely linked to a behavior of interest, the theory of planned behavior does not deny the importance of global dispositions, demographic factors, or other kinds of variables often considered in social psychology and related disciplines. In fact, the reasoned action approach recognizes the potential importance of such factors but, as can be seen in Figure 1–1, they are considered background variables that can influence behavior indirectly by affecting behavioral, normative, and control beliefs. However, whether a particular background factor does indeed have an impact on beliefs is an empirical question. Furthermore, given the large number of potentially relevant background factors, it is difficult to know which should be considered without a content-specific theory to guide selection in the behavioral domain of interest. Content theories of this kind are not part of the reasoned action model but can complement it by identifying relevant background factors and thereby extending our understanding of a behavior’s determinants (see Petraitis, Flay, & Miller, 1995). With the aid of the theory of planned behavior we can not only examine whether a given background factor is related to the behavior of interest but also explain such an effect by tracing it to differences in behavior-relevant beliefs, attitudes, subjective norms, perceptions of behavioral control, and intentions.

The proposition that behavior follows from information or beliefs about the behavior is not unique to the reasoned action model developed by Fishbein and Ajzen ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Contributors

- Part 1

- Part 2

- Index