If most academic historians would now reject monocausal explanations of the witch-craze, it remains clear that there are a number of explanatory perspectives that are generally acknowledged to be valuable: these must now be outlined and contextualised. As we have noted, since the Enlightenment, considerable emphasis has been laid on the contribution of the Christian church to the witch-hunts. There are certainly solid grounds for this. Most known cultures have accepted the existence of witchcraft or phenomena very like it (65), but it was the late medieval Christian church that created a specific image of the witch as a servant of Satan, as an enemy of God, as a being who had willingly joined the Devil’s side in the cosmic struggle between good and evil. Modern reinterpretations of the history of Christianity in the late fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries have taken a rather more nuanced view. The nineteenth-century rationalist’s view of witch-hunting as the outcome of the activities of a bigoted, ignorant and persecuting church has now given way to one that stresses the cultural impact of both Protestantism and Counter-Reformation Catholicism (e.g., 63, 67). A higher level of Christian knowledge and Christian conduct, a more engaged, active, and informed Christianity, were now demanded of the individual Christian. As the twentieth century demonstrated so vividly, this type of official stress on ideological conformity and higher behavioural standards helps create deviants. The witch-hunts, which set in from the late sixteenth century can be interpreted partly as a by-product of those processes of Christianisation that followed the Reformation and the Catholic Counter Reformation, processes which, as the writing of Kramer and Sprenger demonstrate, were already stirring in the later fifteenth century.

The impact of these processes was made weightier by the arrival of what English political commentators of the period would have described as the godly Commonwealth, and what modern historians have called the confessional or sacral state. Whatever else state formation in early modern Europe involved, the emergence of divine right monarchy and confessional absolutism meant that rulers began to take a heightened interest in matters religious, and that the good citizen became more closely identified with the good Christian (the type of Christianity in question was, of course, usually that prescribed by the relevant secular ruler). The connections were spelled out with some cogency by that important historian of Scottish witchcraft, Christina Larner:

If there was one idea which dominated all others in seventeenth-century Scotland, it was that of the godly state in which it was the duty of the secular arm to impose the will of God upon the people … the new regime asserted its legitimacy by redefining conformity and orthodoxy, and by providing a machinery for the enforcement of orthodoxy and the pursuit of deviance.

(67 pp. 5, 41)

In 1590–91 the king of Scotland, James VI, took a leading role in Scotland’s first large-scale witch-hunt. In a pamphlet describing this episode, some of the alleged witches involved were portrayed asking the Devil ‘why he did beare such hatred to the king’. The Devil answered, ‘by reason the king was the greatest enemie he hath in the world’ (35 p. 15). Faced with such statements, rulers, like James, with an enhanced regard for divine right monarchy would develop a very clear notion of where witches fitted into the broader scheme of things, and what ought to be done about them.

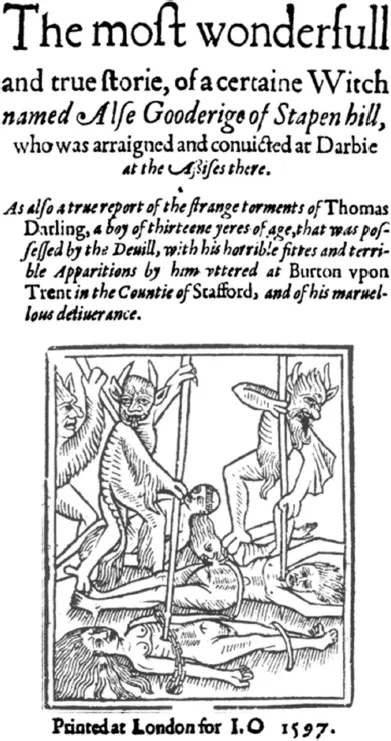

Relating witch-hunting to the activities of the Christian church or of the early modern state essentially presents a view of witchcraft ‘from above’, and is based on analysis of official attitudes as presented in the law code or the demonological tract. This was once the dominant approach to the subject, with little attention being devoted to popular beliefs about witches: indeed, one of the last scholars to write about the witch-hunts in the traditional post-Enlightenment mode, Hugh Trevor-Roper, declared that he was not concerned with what he described as ‘mere witch-beliefs: with those elementary village credulities which anthropologists discover in all times and at all places’ (80 p. 9). From the mid-nineteenth century, however, the tradition grew that late medieval and early modern witchcraft was in fact a pre-Christian pagan religion, adhered to by the peasantry but attacked by the Christian church and the secular authorities. This notion was first formulated clearly by the French radical Jules Michelet in 1862 (71), but it was re-stated powerfully by Margaret Murray in her The Witch-cult in Western Europe of 1921. It was Murray’s theories, reinforced by Gerald B. Gardner’s Witchcraft Today of 1954, which laid the foundations of the currently fashionable view of witchcraft in the late middle ages and early modern periods as a coherent, pre-Christian religion. This idea, which is of central importance to modern Wiccans and pagans, has been largely discredited among academic historians, and any claims that the witchcraft of the period of the witch-hunts might have been an organised and structured religion remain completely unsubstantiated (64).

A much more fruitful approach to the history of witchcraft ‘from below’ was established by two British historians, Alan Macfarlane and Keith Thomas, in the early 1970s (111, 125). Macfarlane was the author of an important book on witchcraft in Essex, his work being distinguished by an exhaustive and imaginative use of court archives and the application of insights on early modern witchcraft accusations derived from twentieth-century social anthropology. Macfarlane’s regional study, like Thomas’s more general work, demonstrated that in England witchcraft accusations were not generally set in motion by judges or clergymen, but were rather the result of interpersonal tensions between villagers. These tensions, on this model often brought to a head by the refusal of charity demanded by the supposed witch, were the outcome of broader socio-economic changes. Under the pressure of population increase, splits between poorer and richer villagers were becoming more marked, not least because the richer ones were adopting a more commercially oriented ethic that challenged older views of communal solidarity. What might be described as a social history approach to the history of the witch-craze had been constructed, and was lodged in a familiar and well-documented model of socio-economic development.

This model, perhaps most neatly labelled as the Macfarlane–Thomas paradigm, will be discussed at length later in this book. What needs to be emphasised here is the importance of the work of these two historians in creating a major shift in scholarly interpretations of witchcraft as a historical phenomenon. Historians working on witchcraft throughout Europe, as well as on witchcraft in England’s North American colonies, began to reinterpret their subject, and search demonological tracts and court archives anew in search of evidence of the popular pressures behind witch-hunting. And, of course, such evidence was found to be widespread, which challenged Macfarlane and Thomas’s assumption that the nature of witch persecution in England was unique, but enriched our understanding of the phenomenon in many other areas. Moreover, historians also began to investigate that other important phenomenon whose importance had been clearly established for the first time by Macfarlane and Thomas, the existence of practitioners of ‘good’ witchcraft, known in England most frequently as cunning (that is, skilled or knowledgeable) men or women. These cunning folk were important in the popular beliefs of the period, and, indeed, it is possible in many areas to find as much evidence of their activities as those of the bad witches who allegedly used occult means to harm or kill humans or their farm animals, to raise storms or to blight the crops.

Another major area of interest among recent historians of witchcraft is the connection between witchcraft and gender, or, more specifically, the reason why something like 80 per cent of those accused and executed for witchcraft during the European witch-craze were women. The question had not been much considered by earlier historians of witchcraft, but it entered the agenda very strongly in the mid-1970s. The crucial development here was the rise of the Women’s Movement in the United States and Europe. Women were at that point consciously struggling to improve their political, economic, and social position and sought to construct a history of oppression, which would help inform their consciousness in their ongoing struggle. The women accused and burnt as witches seemed to provide powerful evidence for man’s inhumanity to woman: thus we find the authors of one work describing the witch-hunts as ‘a ruling class campaign of terror against the female peasant population’ (59 p. 6), and the author of another to describe the hunts as a ‘specifically Western and Christian manipulation of the androtic state of atrocity’, which was ‘closely intertwined with phallocentric obsessions with purity’ (175 pp. 179, 190).

It should be noted that the authors making such claims rarely had much by way of a track record as researchers into the history of witchcraft, while their insistence on the witch-craze as the outcome of oppression and bigotry made them, ironically, among the last proponents of the Enlightenment, rationalist view of the hunts (118). Yet there is no denying that they focused attention on an issue of vital importance that had previously been neglected. Although its exact significance remains unresolved, few of those now researching into the history of witchcraft would deny the importance of the gender element. Conversely, while acknowledging that it was men who wrote the theological tracts decrying witches, passed the laws against them, and ran the courts that tried them, few serious historians would interpret the issue in terms of a simplistic emphasis upon the male oppression of women. Rather more sophisticated approaches have been opened up by the realisation that not only most of the witches, but also a high proportion of those accusing them or giving evidence against them, were also women. On a popular level, witchcraft, for reasons that we shall explore later, was frequently seen as something that operated within the female social and cultural spheres, or, at least, as a specifically female form of power. But this contention must recognise that even i...