- 266 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Written in a personal and engaging style, this book provides a fascinating and informative introduction to the development of surgery through the ages. It describes the key advances in surgery through the ages, from primitive techniques such as trepanning, some of the gruesome but occasionally successful methods employed by the ancient civilisations, the increasingly sophisticated techniques of the Greeks and Romans, the advances of the Dark Ages and the Renaissance and on to the early pioneers of anaesthesia and antisepsis such as Morton, Lister and Pasteur.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A History of Surgery by Harold Ellis,Sala Abdalla in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Medicine1

Surgery in prehistoric times

The word ‘surgery’ derives from the Greek words cheiros, a hand, and ergon, work. It applies, therefore, to the manual manipulations carried out by the surgical practitioner in an effort to assuage the injuries and diseases of his or her fellows. There seems no reason to doubt that since Homo sapiens appeared on this earth, probably some quarter of a million years ago, there were people with a particular aptitude to carry out such treatments. After all, there is an innate instinct for self-preservation among all mammals, let alone man, so that a dog will lick its wounds, limp on three limbs if injured, hide in a hole if ill and even seek out purging or vomit-making grasses and herbs if sick.

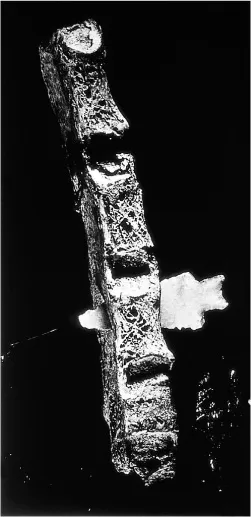

We are talking about a time many thousands of years before written records were kept, and, indeed, the evidence of disease or injuries to soft tissue of that period has long since rotted away with the debris of time. Palaeopathologists (those who study diseases of the distant past), however, have uncovered abundant evidence in excavations of ancient skeletons that fractures, bone diseases and rotten teeth tortured our oldest ancestors. Of course, animals were also subject to all sorts of diseases. Indeed, a bony tumour was obvious in the tail vertebrae of a dinosaur that lived millions of years ago in Wyoming. Other excavations also reveal that injuries were inflicted by man upon man (Figures 1.1 and 1.2) and, as we shall see, that broken bones were splinted and skulls operated upon.

We can make a reasonable guess at what primitive healers may have done from studies carried out by anthropologists and ethnologists (those who study primitive tribes) who, at around the beginning of the 20th century, carried out detailed studies of communities as far apart as West and Central Africa, South America and the South Pacific, who never had contact with ‘modern’ man. It is surely reasonable to surmise that treatments found in such communities, often amazingly similar in different parts of the world, might well match the care given by our prehistoric ancestors in man’s fundamental instincts of self-preservation. The assumption might be wrong, but it would require a great deal of research before a distinction between ‘modern’ primitive and prehistoric medical and surgical treatments could be made. It goes without saying that these early studies are immensely valuable to us today, since few if any primitive communities now remain untainted by Western civilisation.

Figure 1.1 A warrior pierced with eight arrows. Drawn from a rock painting in eastern Spain, and probably the first portrayal of wounding. (Reproduced from Majno G: The Healing Hand. Harvard University Press, 1975.)

Figure 1.2 A flint arrow head embedded in the human sternum. From the Chubut Valley, Patagonia. Musée d’Homme, Paris.

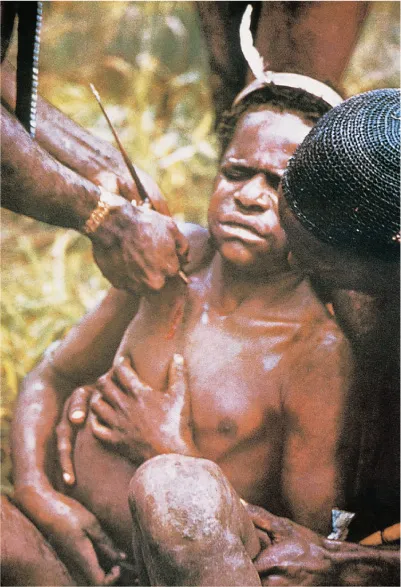

Injuries inflicted by falls, crushings, savage animals and by man upon man demand treatment. Among primitive tribes in the aforementioned studies, open wounds were invariably covered by some sort of dressing. This might take the form of leaves, parts of various plants, cobwebs (which may well have some blood-clotting properties), ashes, natural balsams or cow dung (Figure 1.3). Indeed, even in recent times, dung was used in West African villages as a dressing for babies’ cut umbilical cords, which was responsible for many cases of ‘neonatal tetanus’ – lockjaw in babies – from the tetanus spores that are almost invariably present in faeces.

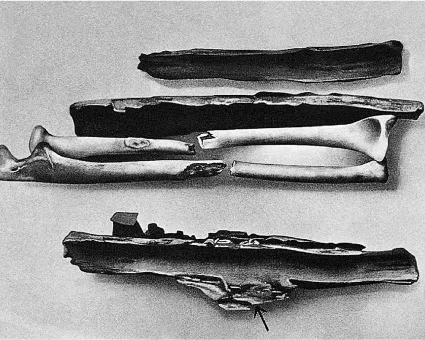

Among the Masai of East Africa, wounds were stitched together by sticking acacia thorns along the two edges of a deep cut and then plaiting the thorns against each other with plant fibre. In India and South America, termites or beetles were employed to bite across the edge of the wound as the lips were held together by the surgeon. The bodies of the insects were then twisted off, leaving the jaws to hold the laceration closed, remarkably like the metal skin clips employed in operating theatres today. Splints of bark or of soft clay (which was then allowed to set) were used to immobilise fractured limbs, and such bark splints have been excavated from Ancient Egyptian burial sites (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.3 A warrior in Borneo, hit in the chest by an arrow, is treated by a healer. This photograph was taken some 50 years ago.

Apart from dealing with wounds and fractures, early surgeons carried out three types of operative procedures, namely cutting for the bladder stone, circumcision and trephination of the skull. The cutting for the stone is such a fascinating and important topic in the history of surgery, it merits a chapter of its own (see Chapter 12).

CIRCUMCISION

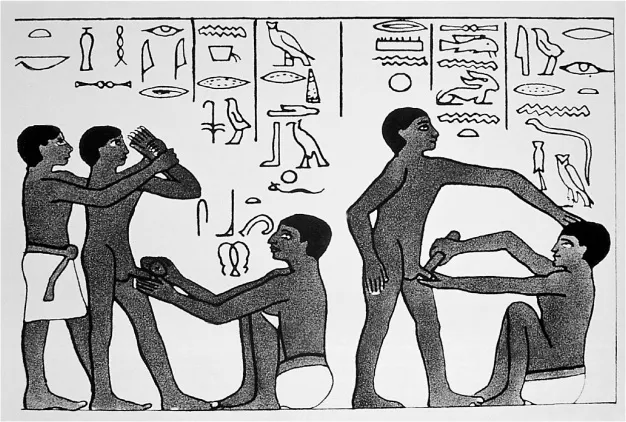

Circumcision might well be claimed to be the most Ancient ‘elective’ operation and was practised in Ancient Egypt by assistants to the priests on the priests and on members of royal families. There is remarkable evidence for this carved on the tomb of a high-ranking royal official, which was discovered in the Sakkara cemetery in Memphis and is dated between 2400 and 3000 BC (Figure 1.5). It represents two boys or young men being circumcised. The operators are employing a crude stone instrument. While the patient on the left of the relief is having both arms held by an assistant, the other merely braces his left arm on the head of his surgeon. The inscription has the operator saying ‘hold him so that he may not faint’ and ‘it is for your benefit’.

Figure 1.4 Fractured forearm bones with bark splints, from Egyptian excavation and dated about 2450 BC. Note the blood-stained lint dressing (arrowed), the oldest specimen of blood. (From Majno G: The Healing Hand. Harvard University Press, 1975.)

The Ancient Jews may have learned the art of circumcision during their bondage in Egypt, and, indeed, circumcision is the only surgical procedure mentioned in the Old Testament, the practice of circumcision among Jews being attributed to Abraham. In the book of Genesis (17; 1–2), probably written about 800 BC, we read: ‘This is the covenant between me and you and your seed which you must obey; all males among you shall be circumcised’. Again, in the second book of Exodus, Zipporah, the wife of Moses, ‘took a sharp stone and cut off the foreskin of her son’.

Early ethnological studies revealed that circumcision was practised widely among primitive communities, including those of equatorial Africa, the Bantus, Australian Aborigines and in South America and the South Pacific, and it was also traditional among Jews, Muslims and Copts. We can only guess at its origins, perhaps as a fertility or initiation rite or possibly for cleanliness or hygiene. Its traditional basis is confirmed by the fact that, in many communities, even though metal instruments were available, the operation was still performed with a flint knife.

Figure 1.5 Drawing of a tomb carving of a circumcision scene. Sakkara cemetery at Memphis, Egypt, c. 2400–3000 BC.

TREPHINATION OF THE SKULL

Undoubtedly, the most extraordinary story in the history of early surgery is that, long before man could read or write, as long ago as 10000 BC, surgeons were performing the operation of trephination or trepanning – boring or cutting out rings or squares of bones from the skull – and, just as remarkably, their patients usually recovered from the procedure.

Although the words ‘trepanation’ and ‘trephination’ today are interchangeable in common practice, trepanation comes from the Greek word trypanon, meaning a borer, while trephination is of more recent French origin and indicates an instrument ending in a sharp point, so it implies using a cutting instrument revolving around a central spike. Trepanation thus connotes scraping or cutting, while trephination describes drilling the skull, as in modern neurosurgical operations.

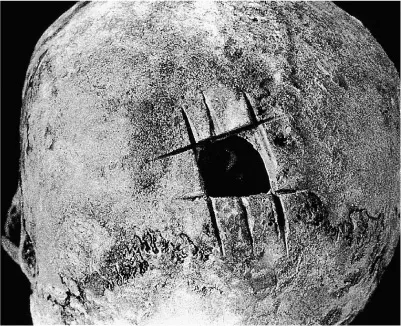

Different techniques of trepanation in Ancient times, and in recent primitive communities, involved scraping away the bone, making a circular groove so that a central core of the bone would loosen, boring and cutting away the bone, or making rectangular intersecting incisions in the skull (Figures 1.6 and 1.7).

This story began in 1865 when a general practitioner, Dr Prunires, who was also an amateur archaeologist, discovered in a prehistoric stone tomb in Central France a skull that bore a large artificial opening on its posterior aspect. With it, he found a number of irregular pieces of bones that might have been cut from another skull. He postulated that the skull had been perforated so that it might be used as a drinking cup. Soon after this, a number of other holed skulls were found in other parts of France and Professor Paul Broca (1824–1880), a distinguished French physician, suggested that these openings were the result of an operation of trepanation and that the instrument employed was a flint scraper. Broca suggested that the survivors of the operation were thought to be endowed with mystical powers and that, when they died, portions of their skulls, especially those that included a part of the edge of an artificial opening, were in great demand as charms.

Figure 1.6 Trephined skull from an Anglo-Saxon skeleton excavated in East Anglia.

Figure 1.7 Trepanned skull from Ancient Peru. The operation has been performed by means of a series of incisions placed at right angles to each other.

Following these discoveries, thousands of such specimens have been discovered in many parts of the world: the United Kingdom (Figure 1.6), Denmark, Spain, Portugal, Poland, the Danube Basin, North Africa, Palestine, the Caucasus, all down the western coastline of the Americas and, especially, in Peru (Figure 1.7), where more than 10,000 specimens have been excavated.

Two questions immediately came to mind: why was the operation performed, and how? In many cases, it seems that trephination was carried out on patients following a head injury. We can see an obvious fracture line on many specimens, often coinciding with, or near, the site of the trephine defect. We can be sure that many such patients recovered because numerous specimens show clear evidence of healing of the fracture and of the edges of the trephined defect. The frequent use of stone clubs and sling stones among Ancient warring Peruvians may account for the large number of specimens recovered from that country; in one collection of 273 skulls from Peru, 47 had been trephined from one to five places. We can only guess at the frequent use of trephination in skulls with no obvious evidence of injury. In many of these, indeed, the operation had obviously been performed several times at intervals. Intractable headaches, epilepsy or an attempt to confer mystical powers on the subject are all possible motives, and there seems little doubt that the fragments of bone removed were themselves often regarded as possessing magical powers.

Of course, the operation was performed without the benefit of anaesthesia, although authorities have surmised that an extract of the coca plant might have been used by the Ancient South American practitioners. The instrument would originally have been a sharpened flint or piece of obsidian (a hard black laval stone), fastened by cord to a wooden handle. These were later replaced by a copper or bronze blade. Techniques varied from place to place: a circular cut through the skull bone, a series of circular drill holes that were then joined together, or triangular or quadrangular cuts through the skull bone. Broca, who we mentioned earlier, showed that he could produce such a defect in a skull in 30–45 minutes using an Ancient flint instrument. Even more remarkably, in 1962, Dr Francisco Grana of Lima operated on a 31-year-old patient, paralysed after a head injury, and evacuated a blood clot from beneath the skull using Ancient Peruvian chisels to trephine the bone. The patient recovered.

Our knowledge of prehistoric trephination would remain mainly a matter of conjecture if it were not for the fact that the operation was still being performed by primitive races in some widely separated parts of the world, the South Pacific, the Caucasus and Algeria, at the end of the 19th and in the early 20th century. From New Guinea and the surrounding islands of Melanesia, many skulls have been collected, which show perforations similar to those found in Stone Age specimens.

Writing in 1901, the Reverend J. A. Crump noted that in New Britain the operation was only performed in cases of fracture, which was a common injury in tribal warfare. The instrument employed...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Authors

- 1 Surgery in prehistoric times

- 2 The early years of written history – Mesopotamia, Ancient Egypt, China and India

- 3 Surgery in Ancient Greece and Rome

- 4 The Dark Ages and the Renaissance

- 5 The age of the surgeon-anatomist: Part 1 – from the mid-16th century to the end of the 17th century

- 6 The age of the surgeon-anatomist: Part 2 – from the beginning of the 18th century to the mid-19th century

- 7 The advent of anaesthesia and antisepsis

- 8 The birth of modern surgery – from Lister to the 20th century

- 9 The surgery of warfare

- 10 Orthopaedic surgery

- 11 Breast tumours

- 12 Cutting for the stone

- 13 Thyroid and parathyroid

- 14 Thoracic and vascular surgery

- 15 Organ transplantation

- 16 Envoi: Today and tomorrow

- Index