- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Since the early 1990s interest in foresight has undergone one of its periodic resurgences and has led to a rapid growth in formal foresight studies backed by governments and transnational institutions, including many from the United Nations. However, texts that counterbalance in depth practical experience with an exposition and integration of the m

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Foresight by Denis Loveridge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Systems and foresight

Chapter 1

Foresight and systems thinking

An appreciation

The more and deeper you think, the more there seems to be no real ‘answer’ to a situation.

Denis Loveridge 2007

Exploration

A. A. Milne often used his much-loved creation Pooh Bear to deliver homilies to his readers, old and young alike. Pooh’s homespun thoughts have much to commend them, especially in the marriage of foresight and systems, if only for their illustration of the interconnections between all forms of life, the qualities of art and the situations they create. The words ‘foresight’ and ‘systems’ are common enough in human discourse; there is nothing remarkable about them. In English, the language I am most familiar with, foresight is referred to ubiquitously. Its occurrence in all manner of conversations and writings is one thing, but its difficulty has been acknowledged by Whitehead (1964); similarly for systems, a word that is scattered like confetti throughout normal discourse without paying much heed to its various meanings. In this chapter a system is regarded as an assemblage of interrelated elements comprising a unified whole with emergent properties. The interrelationships may or may not be fully specified or understood. Systems thinking when ‘… applied to human activity [is] based upon four basic ideas: emergence, hierarchy, communication and control as characteristics of systems … [in which] … the crucial characteristic is the emergent property[ies] of the whole’ (Checkland 1981: 318). However, the words foresight and systems hide massive debates and literature, not about their lexicographic meaning which the Oxford dictionary sets out simply, but about the concepts that both words mask. Unmasking this debate to remove some of the mystique that surrounds both is my purpose in this chapter, and in doing so to set the content of both in context. It is not my intention to review the immense literature relating to foresight and systems which show little, if any, interconnection between the two (Saritas 2006: 4) (Note 1). Nor is it my intention to describe methods used in foresight; these are mostly derived from technology forecasting and other kinds of forecasting, or in modelling systems that have been described elsewhere.

Foresight

Foresight is – and remains – essentially practical and qualitative anticipation; there is no comprehensive discussion of it in theoretical terms, though Chapter 2 will deal with some theoretical matters. However, that does not mean that I view foresight as some kind of ‘wild card’ guessing game, far from it. The Oxford dictionary attributes several characteristics to foresight that divide neatly into soft (the action of looking forward and caring for or provision for the future) and hard (the muzzle sight of a gun) connotations. These two attributes are interrelated, a matter that is often overlooked in anticipation of the future, where the unpleasant fact of human conflict, greed and war are often set aside. It is here that another unavoidable matter intrudes, that of the importance of, and fascination for, numbers with all their vagaries between information and misinformation. Numbers invoke notions of precision that are not characteristic of foresight nor of its close relative, forecasting. Confirmation of this lies in the Oxford dictionary which refers to forecasting, among other similar descriptions, as ‘to estimate or conjecture beforehand’, an ability that can only take place after foresight has marked out the subject for forecasting. The fascination for, and abuse of, numbers is a serious matter that Funtowicz and Ravetz (1990a: 28) discuss at length through their NUSAP scheme; more will be said about this in Chapter 2.

Elsewhere (Loveridge 2001: 781) I have separated foresight, the individual or small group activity of anticipation, from Foresight as the formal process that is now popular in policy and planning circles. I forthrightly called the first real foresight and the second institutional Foresight, claiming that the first is separated from the second by random time intervals that may run into centuries (the latter claim arose from Leonardo da Vinci’s outpourings in the late 1400s, many of which came to fruition in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries); typically the time interval may be about 20 years with a spread from 10 to 40 years. Often real foresight occurs at a time when the polity either cannot recognise its importance or has a mindset that denies its implications. By contrast, institutional Foresight takes place later and in a different milieu in which the polity’s mindset has moved beyond denial and the institutional association makes the implications more acceptable and recognisable. If real foresight is original, institutional Foresight becomes a process of rediscovery and aggregation. Both serve their purpose, but it is not to be supposed that the institutional variant is or can be designed to have the characteristics of its real counterpart. These are not empty claims. It is now 30 years since I pointed out to the company I then worked for that the world’s population and its needs distributions were likely to alter world markets drastically in distribution and kind, pointing specifically to China and Asia, where India predominates. Equally, it was not difficult to recognise, at about the same time, from the UK’s Social Trends, the way the UK’s population had become locked into a cyclical pattern at a total fertility rate of around 1.7, less than the replacement rate. The consequences, in terms of the necessary future wealth-generating capability of the rising generations through the 1980s and onwards – dependency ratios, an ageing population, immigration and emigration, and other matters – were clear enough by the early 1980s to be indicated to the company and later to enable me to teach about them to an undergraduate course from 1992 onwards. There are many other examples where the centrepiece of institutional Foresight studies fail because, even in 2008, they are conducted on the basis of classic reductionism; the systemic interrelations are rarely made.

In the Introduction I referred to institutional Foresight’s slow and unobtrusive mutation toward what is believed to be scenario planning. The shift has been real enough and in the UK Government’s Foresight group this emphasis is referred to directly. The words ‘visions’, ‘alternatives’ and the post-modern word ‘narrative’ have come onto the scene to the extent that the Foresight process is now referred to in much the same way as the planning process used to be. The extent to which this similarity has advanced can be gleaned from Miles and Keenan (2002: 15) in their ‘Practical Guide to Regional Foresight in the United Kingdom’ where they claim that:

The term ‘Foresight’ [is understood] “to describe a range of approaches to improving decision making … Foresight involves bringing together key agents of change and sources of knowledge, in order to develop strategic visions and anticipatory intelligence. Of equal importance, Foresight is often explicitly intended to establish networks of knowledgeable agents”. (Note 2)

However, this shift has not embraced the full context and content of scenario planning, leaving the Foresight process with both feet in mid-air, an expression used by Donald Michael in his reflections on thinking about the future (Michael 1985: 94). Foresight, real or institutional, enables visions of the future. While life is the present, anticipations of the future are an inevitable part of that present. The purpose of visions of the future is to attempt to identify, as far as one sensibly can, different kinds of futures in which life may take place. For example, in 2001 the argument in the UK about joining the single European currency and involvement in Europe’s further political integration ignored the 1974 report by Lord Kennet, a UK parliamentarian, that openly acknowledged that political union was Europe’s ultimate aim (Kennet 1976). If people in the UK did not know that, it was because the question was not asked. In 1956, Jan Monet and his associates’ vision was of an integrated Europe free from war. There are other visions for the future of Europe, some of them distinctly unpleasant.

Visions of the future are there because they are inevitable; without them the polity can neither develop nor policy be created. However, one property a vision must have was neatly summed up by Al Haig, the one-time US Secretary of State, that ‘… vision without discipline is daydream’ (Haig 1984). Foresight is an essential precursor to creating vision and is needed to prevent daydreaming; in that way foresight enables policy to be shaped.

In its current context, the Foresight process is said to be systematic, within the often undefined boundaries of study. Within this frame, the reductionist overtones of systematic inquiry cannot be evaded. However, this creates an oxymoron as neither a systematic nor a reductionist way of caring or providing for the future is possible for something that does not yet exist. By contrast it is possible to anticipate possible future events that, when taken together, describe a set of perceptually bounded, imagined future situations; this is a systemic, not a systematic, way of proceeding because it is opinion centred, deals in uncertainty and alternatives, and relies on what Vickers means by comprehension (Vickers 1963), which will be discussed shortly.

What can be concluded about foresight at this point? First, that the real variant identifies a series of either random or pseudo-random and specific future events, anticipated by individuals or groups often within well-defined boundaries, that are widely ignored or denied when first recognised. The interrelationships between these specific future events and the present are not always sought or displayed, though in the best circumstances they are. Although the notions of a paradigm and a paradigm shift (Kuhn 1962) are usually reserved for scientific theory, real foresight is closely allied to these events. Characteristically, the events described by real foresight, at their time of identification, are of low probability of occurrence, but of high information content describing highly unusual matters or patterns of them. Second, the institutional variant is mostly concerned with rediscovery of past real outpourings and aggregation of them into collections of ideas, often in an ad hoc way, that are perceived to be related to a problem, however broadly that may be described. Characteristically, these collections of ideas are of high probability of occurrence and low information content, because much more is known about the ideas involved.

Systems thinking and its influence

What then of systems and systems thinking? Systems thinking can touch every form of human and natural activity; it is this propensity that has, in the past, led to extravagant claims for its capabilities with the attendant risk of disrepute, typified by the highly critical papers by Phillips (1969: 3) and Lilienfeld (1978: 191) in which general systems theory is dissected closely (Phillips’ and Lilienfeld’s criticisms will be explored at greater length in Chapter 2). Other than simple lexicographic descriptions it should be obvious that formal definitions of ‘system’ robs the term of its depth and complexity. Flood (1999) attempted to clarify the position relating to systems thinking as follows:

‘Systemic thinking is then not something that can be explained easily and understood comprehensively … Very quickly we will lose touch with the notion of wholeness in a trivialised account of its so-called properties. Many textbooks … make this mistake … explain the world in terms of systems and subsystems, what a system is and how it behaves. An account in these terms … strips it [systemic thinking] of all essential meaning. Systemic thinking begins with an intuitive grasp of existence’

(Flood 1999: 82)

Flood’s comment indicates the well-known systemic tenet that phenomena can never be wholly known for the very reason that we are part of them, a notion that stems from gestalt psychology and Smuts’ original writing on holism (Smuts 1926) and, more remotely, from a sociological adaptation (or corruption) of the uncertainty principle (Heisenberg 1927). Flood’s point is well made, giving more cause to avoid formal definitions of ideas that are shaped by the plasticity of the human mind.

Von Bertalanffy (1929) set out the beginnings of systems and systems thinking especially to challenge reductionist thought that dominated science at the time and in many ways still does. For von Bertalanffy reduction was not a viable way to study living biological phenomena that needed to be set in the context of other phenomena with which they interacted, with increasing complication, and from which they gained their life support. What may loosely be called the systems movement sprang from von Bertalanffy’s original work and led to the formation of the Society for General Systems Research in the 1940s. Many times since attempts have been made to define systems thinking, particularly during the early post-World War II development of operational research (e.g. Churchman 1968); mostly, as Flood maintains, these efforts have been counter productive.

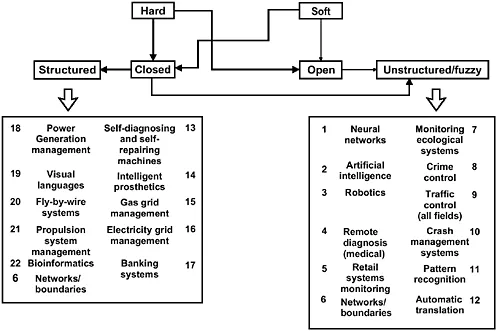

Checkland sets out a chronology of the rise of systems thinking (Checkland 1981: 59), which I will not repeat here, in a way that also indicates problem areas that systems thinking faced at the time and mostly still does. In his review, Checkland claimed that Aristotle argued that the sum is greater than the parts in any set of interconnected elements, but it remains unclear when the modern notion of thinking about situations as a whole, systemic thinking, began to be used. Jan Smuts (1926) may be the person who marked out holism in its modern idiom. Dictionary descriptions indicate that systems are collections of items that are interconnected or interrelated. Checkland (1981) goes further to claim the nature of these collections, with their interconnections, to be a model, hierarchical in structure, with emergent properties and with communication and control aspects. With the passage of time, the focus of attention in systems research fragmented into many themes that are summarised in Figure 1.1 and not simply into hard and soft systems.

Throughout the different streams of systems activity, interdependencies are prominent features; these become ever-more so as the differences between the traditional notions of hard and soft systems blur. Process control theory and its applications are the most easily recognised, though nowadays the term ‘process’ has to be interpreted more widely than its original intention. For example, the ever-growing use of algorithmic stock market trading is a far cry from manufacturing process control, but it is turning what was seen as a soft activity, based on human intuition and judgement, into a hard, if not mechanised process. Similarly, fly-by-wire aircraft represent an extreme development in control systems as do remotely controlled ‘drone’ weapons systems. There are also attempts, some successful some not, to manage recruitment and the flows of patients in health systems as a hard, mechanised process. At one time, hard systems would have been regarded as complicated, but well specified and understandable. These contentions have become less sustainable as processes have become ever more complicated, a feature exemplified by analyses of accidents (Perrow 1984) in many fields (e.g. Three Mile Island, Apollo 13 and forms of medical diagnosis) that indicate the presence of complexity that human operators find difficult to comprehend.

‘Situations’ are systems which may be characterised as ‘a regularly interacting or interdependent group of items forming a unified whole’ (Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary) taking the form of ‘a social, economic, or political organisation or practice’. Checkland (1981: 317) takes these formal descriptions further, but in a different direction when describing a system as a model of a whole entity that ought to relate (this ought not to be a matter of choice!) to real-world activity that, in human made entities, have emergent properties as a crucial characteristic. Many of the notions laconically mentioned above recur in one form or another throughout this and later chapters. It is at this point that the temptation to embark on a definition of systems thinking, is strong, but it is one that I will resist.

Figure 1.1 Streams of systems thinking and applications

Living systems are usually thought to be soft, by default. They can be of infinite variety. Here, though, there is a more subtle separation within soft systems thinking between natural systems and human societies, organisations and their management, and behaviour. The effort put into understanding these activities has been and remains immense, and has become the subject of major modelling work. However, the separation of systems into hard and soft variants is immediately seen as naive as science and technology and social thought continue to blur the separation between the two. It is here that the more contentious aspects of systems now lie. The claim for systems to have emergent properties that lie beyond the properties of an assemblage of well-understood components, the gestalt aspect of systems, leads inexorably toward an argument for what Sheldrake (1988) and others have called the presence of the past. The importance or otherwise of Sheldrake’s notions will be discussed further in Chapter 2. On occasions this has been dubbed a ret...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I Systems and foresight

- PART II Scenarios and sustainability

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Figure credits