![]()

Part 1

Dynamical Music Interaction Theories and Concepts

![]()

1

The Interactive Dialectics of Musical Meaning Formation

Marc Leman

Introduction

Interactions with music (such as listening, dancing, performing) are based on bodily activities that co-determine perception and meaning formation. The theory of embodied music cognition thereby assumes that listeners assess music in terms of action-states that could have caused the particular expressive character of the music, thus providing a ground for further meaning formation (e.g., Leman, 2007, 2016). For example, given the virulent nature of the soundscape experienced through interacting, an energetic action-state may be inferred that could have caused this expression. This action-state may be further associated with imagined agents or other elements of narratives. In this chapter, we focus on the idea that assessments of music may change “on the fly,” while interacting with music. Meaning formation is thereby conceived as an emergent outcome of dynamic processes based on embodied music interactions and their assessments.

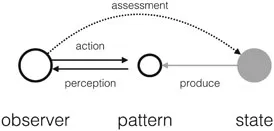

A model of assessment is shown in Figure 1.1. Basically, the inferred action-state refines a prediction model for future assessments of moving sonic patterns (the music as sound). Using an overt enactment, such as gesturing along with the expressive musical affordances for moving (Godøy, 2010), the inference of the action-state can be facilitated. Seen from that perspective, embodied interaction with music supports an ongoing meaning formation process, in which actions allow for continuous refinement of the prediction model. “Ongoing” here means that assessments are in fact changing, on account of changing musical configurations, changing interaction patterns (due to attention, movement), and changing contexts (in concert, at home, during functional or aesthetic listening).

Figure 1.1 A model of assessment. The observer interacts with a pattern (sound) and generates an estimate about the state of being that might have produced the observed pattern. An enactive assessment would imply that the assumed state is an action-state, which the observer connects with the own repertoire of action experiences.

Examples of Conflicting Assessments

Imagine that one improvises on a blues melody in the key of C (the example is taken from Leman, 2016). One option is to start the improvisation on a C7 chord in order to clearly establish the key. Some reference to the F7 chord in measure 2 would then be welcome as confirmation of that tonal space, to be confirmed until measure 3. However, to rouse the audience’s attention, it may then be an option to play “out of key” on a Gb pentatonic, say, in the fourth measure (using the notes Gb, Ab, Bb, Db, Eb), where the chord progression is Gm7 and C7. In the fifth measure, it is then possible to resolve this pentatonic to the F7 chord, in order to reinforce the initial tonal space.

From the listener’s point of view, the Gb pentatonic is used as a staircase towards F7, as it is outside of the tonal space introduced at the outset. This creates an unexpected tension and perhaps even tonal disorientation. However, at the F7 chord, this tension is resolved and the staircase itself now matches with the tonal center of the blues. The “punch” (when hearing Gb) is an incentive to re-assess the tonal space. As a result, the listener’s new predictive model of the tonal space will be broader and more comprehensive than the originally assumed tonal space.

The assessment dynamics described in this example can be conceived of as a dialectic, or triadic transformation, involving thesis (here: the assumption of the key of C as cause of the generated harmony and melody), antithesis (playing Gb, or the negation of the assumption of the C key), and synthesis (resolving Gb into the C key from the viewpoint of a broader tonal space spanning of the keys of C and Gb). Due to this dialectic, the assumed tonal space becomes broader and more reified, spanning territory that goes beyond just the key of C. This tonal space defines expectancies for musical pitch and chord sequences, and this model may be part of an overall prediction model that incorporates rhythmic, stylistic, and other possible state descriptions.

To clarify this interactive dialectic a little further, it may be instructive to consider a second example, now concerning the adaptation of human movement-rhythms to those in music, such as dancing to the beat, or being in synchrony with the other players in a musical ensemble. Assume a context in which we play music with friends. In this context, being in sync (thesis) and being out of sync (antithesis) offers a setting for conflicting assessments about timing. The conflict resolves thanks to a re-assessment of the in-out syncing (the synthesis), in which we assume that timers attract and influence each other in a game-like manner, like teasing, or pulling and pushing of objects that manifest themselves over time. The re-assessment emerges from the interaction of several ongoing events and processes, such as the musical stimulus, the human sensorimotor and prediction system, the movements of limbs, their timing responses, and natural neuromuscular variability. The outcome of the interaction may be an awareness of the causes of groove, which may be attributed to timing conceptions of our friends, including ourselves.

Note that in the examples given, meaning—here understood as an awareness that emerges from a particular interactive context—does not arise from a single assessment but from a process involving assessments and reassessments. The result is a series of “on-the-fly” assessments in which tension and relaxation or conflict and resolution are co-determined by stimulus properties and actions, which define a dynamic interactive context for meaning formation. This viewpoint resembles related viewpoints in different ways, for example, as a dynamic of surprise (Huron, 2006; Meyer, 1956), implication-realization (Narmour, 1990), or tension and relaxation (Lerdahl, 2001).

The Embodied Basis of State-Assessments

As suggested in Figure 1.1, state-assessments are estimations about the causes of our perceptions, and these causes are refined using interactions, which in turn refine our perceptions. The embodied basis of state-assessments, which facilitates the inference of these state-assessments, can be clarified by considering examples of gestural conditioning and examples of corporeal dispositions that co-determine perception as well as movement (Leman, Nijs, Maes, & Van Dyck, 2017).

First, consider gestural conditioning. This happens, for example, when subjects “bounce along” (or are being bounced along) to a metrically ambiguous external stimulus, in a binary or ternary manner (that is, they keep time with the stimulus by moving along with its impulses, in groups of two or three). The bouncing gesture in question may condition the preference for binary or ternary accentuations perceived in that stimulus (Phillips-Silver & Trainor, 2007). Similarly, dancing a happy or sad choreography along with an ambiguous musical expression may condition the assessment of the perceived musical expression accordingly (Maes & Leman, 2013). These and similar findings suggest that explicit gestural conditioning is an important component of musical assessment (Maes, Leman, Palmer, & Wanderley, 2014).

Next, consider biological dispositions for tonal perception. These dispositions are typically complemented by higher-level cognitive schemes that represent habituations with the musical repertoire in question (Bigand, Delbé, Poulin-Charronnat, Leman, & Tillmann, 2014; Collins, Tillmann, Barrett, Delbé, & Janata, 2014). Yet, this biological disposition generates the basic support structure for the assessment of tonality at this higher cultural level. This support structure is compelling because it is grounded in auditory neuronal mechanisms working on acoustical structures (see Langner, 2015). The biological dispositions are directed toward particular tonal environments, which are facilitated and reinforced by the introduction of new structures to that environment. As a matter of fact, the music repertoire reveals structures that comply with the biological dispositions. After all, the repertoire draws upon these support structures and reinforces their compelling nature, through habituation. Seen from this perspective, assessments of tonal states are conditioned by embodiment. These assessments provide a basis for meaning formation, ranging from feelings and awareness of tonal shades to higher-level conceptualized chord and key functions used in practice by expert musicians.

Another example is beat-synchronous movements, where we can observe resonances of the human body (Styns, van Noorden, Moelants, & Leman, 2007) and sensorimotor predictions that capitalize on these resonances (Moens & Leman, 2015). The outcome is a compelling embodied force that regulates the adaptation of the human sensorimotor rhythms to external musical rhythms (Nozaradan, Peretz, & Mouraux, 2012; Schaefer & Overy, 2015). The resulting entrainment mechanism enables the establishment of a stable overall timing framework that allows the structuring of attention, harmonic rhythm, and other expressive features (Large & Jones, 1999). However, once a stable form of interaction can be maintained, it can also be negated, resulting in a dynamic of stable-unstable synchronization that can be assessed as a meaningful principle in its own right, as suggested in the previous section.

Overall, listeners’ interactions with musical stimuli are supported by biological dispositions and cultural habituations that condition assessments of the stimuli. In turn, these assessments serve as guidelines for future interaction and possible cognitive valuations and meanings. From this viewpoint, the interactive dialectic of changing assessments can be seen as a mechanism that regulates the continuous update of prediction schemes, using new external stimuli, existing dispositions, and habituations as a source of information.

Meaning Formation as Layered

Several authors have pointed out that meaning formation is layered (in the sense that it ranges from more embodied meanings to more conceptual meanings). For example, according to Broeckx (1981, 1986), physical properties of musical sound such as frequency, spectral density, and loudness give rise to impressions of visual and tactile space, such as extension, density, weight, smoothness, roughness, hardness, softness, liquidity, ephemerality, flatness, consonance, dissonance, and other impressions. These impressions apply to assessments of interactive experiences and the “intuitive apprehension of their inherent meanings” (Broeckx, 1997, p. 273). Broeckx thereby asserts that these assessments are not merely metaphors, because the assessments do not require an intellectual bridge between musical sound and its associated affective experience. Instead, the assessments become immediately apparent through “apprehension” of the musical and interactive situation. In line with the theory of embodiment mentioned here, assessments draw upon synesthetic and kinesthetic experiences, such as spatial orientation, material density, auditive coloring, and different degrees of momentum of sounds. The words used to describe these assessments capture this experience of meaning metaphorically, but this in itself is a consequence of translating lived experiences into words (Lakoff & Johnson, 2008; Reybrouck, 2014).

According to the description of embodied assessments given above, experiences give rise to meanings as soon as they imply an assessment of the state of the observed phenomenon (Figure 1.1). However, as suggested above, meaning formation may also be characterized by higher-level associations, such as the passage in Beethoven’s Symphony that expresses victory or the passage in Mozart’s music that expresses jealousy. Both victory and jealousy conceptualize what the music could signify in a more broadly defined associative context; for example, related to historical events, human nature and social relationships, natural phenomena, ancestors, and divine beings. At that high cognitive level, musical meaning results from an assessment (and awareness) of the music’s program—the deeper general expression of what music signifies for people. Metaphors, narratives, worldview, and beliefs are often used at this level of musical meaning formation.

In short, musical meaning formation can be conceived in layers, which represent, in turn, lived embodied experiences of sensed qualities of sounds, pre-reflective awareness of these lived qualities as being present while listening, reflective representation of these qualities as concepts, and finally, verbal summaries and narratives of the lived experience.

Interactive Dialectics as Pragmatic Logic

Interactive dialectics can be seen as a dynamic model that regulates changes in state-assessments during embodied interaction with music. The question is how this dynamic model can be further defined. Historically, attempts to formalize this dynamic model have been conceived in terms of formal logical systems, which describe conflict and conflict resolution of conceptualized meanings as a form of “reasoning” (Apostel, 1979; Kunst, 1978). These logical systems are discussed here as they provide a particular historical perspective on the dynamics of meaning formation. In modern conceptions, one may wish to define the model in terms of Bayesian inferencing (Friston, Mattout, & Kilner, 2011).

The work of Apostel (1979) is relevant because he clarified the underlying dialectic reasoning in the writings of Hegel and Marx, using several types of formal logics such as temporal logics, action logics, and modal logics. He then used these logical systems to describe human actions and assessments about those actions. In a similar way, Kunst (1978) aimed at capturing the dialectics of meaning in art, using formal modal logics as a tool for describing changes in assessments...