The circle, the square, are the letters of the alphabet used by the architects for the structures of their best works.1

—Claude Nicolas Ledoux

Long before books were printed and the Internet established worldwide connectivity, architecture was the most accessible and durable form of public media. Architecture emerged as a conduit of cultural expression whose greater function had been to frame rituals, consecrate sites, suspend thresholds between sacred and profane zones, and articulate these spatial performances in conjunction with meaning written on and by its material surfaces. If past civilizations combined inscriptions, symbolic images, and sculptural groups on building surfaces as allegorical programs to expand legibility to less literate audiences, then the complementary presence of words and symbols on today’s architecture remains the most direct means of ascertaining a building’s purpose. In short, focusing on the words, signs, symbols, and emblems appended to a building offers a good place to start to read architecture. While neon lights and digital screens may substitute for words carved in stone, studying the signs and symbols of these more recent contributions to writing on buildings merits the same close attention epigraphists apply to deciphering ancient inscriptions. Inscriptions and their contemporary counterpart of signage may directly or indirectly identify a building or monument’s purpose, construction period, patron, architect, historical context, or poetic aspirations. When it comes to reading architecture, then the first place to start is by seeking out any words, epigraphs, icons, numbers, or symbols that may be appended to it.

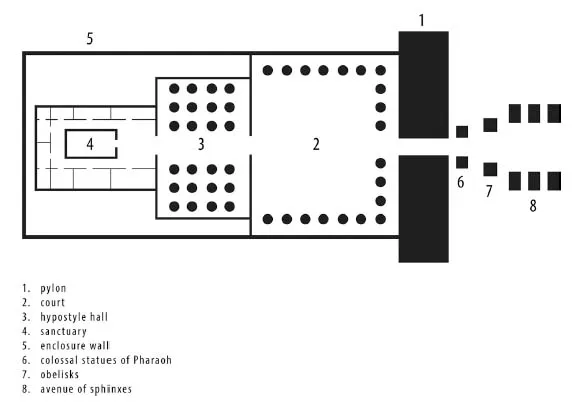

Emblematic of the space that writing occupies in ancient architecture, the great hypostyle hall of Amun-Re at Karnak in Egypt features inscriptions, cartouches, and bas-relief sculpture on every surface. Built during the time of Sety I (reigned 1294–1279 BCE) and his son Ramesses II (reigned 1279–1213 BCE), the hall’s dense intercolumniation represents a primordial papyrus thicket, while its relief carvings illustrate historical and religious stories. This petrified forest contains 12 giant columns in the central space, or nave, standing at about 70 feet tall and 10 feet wide, and 122 columns at the lower side aisles standing at about 33 feet tall. The hall’s surfaces depict the daily rituals priests conducted in the temple sanctuary. The sanctuary was the house of the deity, the final and lowest room in the temple’s processional route that led from an entrance pylon to a peristyle court to a hypostyle hall to the final naos or central shrine. Papyrus column capitals, with open blossoms in the nave and closed buds on the flanking aisles, represent the mythological marsh of creation and the fertile Nile flood plain from out of which they grew. The entire hall operates at multiple levels and scales of legibility: as a shelter for religious practices, an edifice that depicts the rituals it instantiates, a primordial grove, and the deity’s domicile.

Figure 1.1 Diagram of a typical Egyptian temple, drawn by Gavin Friehauf

Painted in bright colors, bas-relief sculpture depicts temple rituals and augments the hieroglyphic inscriptions of sacred rites so that even an illiterate public would have been able to glean the message of scenes such as the pharaoh being crowned with a diadem, sacrifices to Amun-Re, or the procession of annual festivals. These engraved surfaces also depict the foundation rites of the temple itself, including such tasks as surveying, designating a sacred boundary, and molding a brick. In temples such as those at Karnak, extensive textual references and ornamental programs transform the building into a guidebook of itself, where deep ritual mysteries are carved on stone pages.

Hieroglyphs mythologize the origins of writing, a gift that liberated people from the burden of having to preserve stories through memorization. This gift, however, was paradoxical. Writing in Phaedrus, Plato described the discovery of writing as a pharmakon: a cure that also acts as a poison. According to Egyptian legend, the god Theuth (Thoth) developed the art of letters among his other inventions of arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy. The Egyptian King Thamus replied to this offering with circumspection, arguing that “this discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves.”2 A prescription to save memory, inscription transforms the surfaces of architecture—an art form whose endurance uniquely ties to the ars memoriae or memory arts—into permanent historical records, and indeed into books. But, in this poison–cure dynamic the pharmacological tensions between inscription, prescription, architecture, writing, forgetting, and remembering also identify a fundamental rivalry between words and buildings. Does writing render buildings into mere surfaces awaiting inscriptions or does architecture’s monumentality dwarf the words inscribed on its walls? For John Ruskin, a 19th-century architectural critic: “It is as the centralization and protectress of this sacred influence, that Architecture is to be regarded by us with the most serious thought. We may live without her, and worship without her, but we cannot remember without her.”3

Figure 1.2 Transverse section of the Great Hypostyle Hall from the Precinct of Amun-Re in the Karnak Temple Complex at Thebes. From Description de l’Égypte: ou, Recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypte pendant l’expédition de l’armée française publié par les ordres de Sa Majesté l’empereur Napoléon le Grand (Paris: Imprimerie impériale, 1809–1828)

Figure 1.3 Ramesses II molding a mud brick before Amun-Re using a wooden mold, a ritual similar to laying the cornerstone of a building ceremonies, from the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak. Photo by Dr Peter Brand and image courtesy of P. Brand/Karnak Hypostyle Hall Project

Trajan’s Column, a commemorative columna cochlis in Rome dating from 113 CE, offers a case in point to demonstrate this rivalry. It is a marker that depicts sequential sculptural groups of the emperor’s two victories over the Dacians on a narrative frieze spiraling fr...