- 250 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

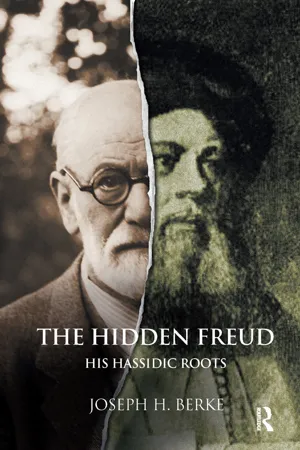

About this book

This book explores Sigmund Freud and his Jewish roots and demonstrates the input of the Jewish mystical tradition into Western culture via psychoanalysis. It shows how Freud utilized the Jewish mystical tradition to develop a science of subjectivity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Hidden Freud by Joseph H. Berke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Sigmund Freud and the Rebbe Rashab

By 1903 Sigmund Freud was evolving from a neurologist to a psychoanalyst. This term had been proposed by Freud several years beforehand. He first used the term in 1896, in French and then in German (Gay, 1988, p. 103). It denotes an expert in matters of the mind who aims to alleviate emotional and physical distress through psychological means. But Freud’s transformation was by no means straightforward. For years he explored physical treatments for the relief of physical and emotional illness. One of these was the use of cocaine as a stimulant and cure for morphine addiction. In fact, Freud narrowly escaped becoming famous for discovering the analgesic and anesthetic properties of coca. He was very upset that he had missed a chance for professional recognition and advancement (Clark, 1980, pp. 58–62). However, such a success could have undermined his emerging focus on psychological processes.

Freud wavered between his identity as a rational scientist and his explorations of subjective worlds: Dreams, free associations, and kindred eruptions of the unconscious. He was not the first to note the power of unconscious impulses. Toward the late nineteenth century writers like Carl Gustav Carus declaimed: “The key to the knowledge of the nature of conscious life of the soul lies in the realm of the unconscious” (ibid., p. 115) and the prominent psychiatrist, Henry Maudsley, insisted that the most important part of mental action was unconscious mental activity (according to Clark, ibid., p. 116). Freud was the first to systematically investigate the hidden basements and subbasements of the mind. He showed how they are built, what they contain, and how they affect and behavior.

Initially Freud turned to hypnosis as a means of delving into these psychic recesses. He had some success with helping people to part with their disturbing symptoms through the power of suggestion. He would put a person into a trance and direct him to relinquish whatever was bothering him when he woke up. He quickly realized, however, that there were many people who were not amenable to hypnosis. Even in those who were, he found he could achieve the same results by ferreting out the onset of their troubles and by allowing them to talk freely about their experiences.

“Anna O” was “the germ cell for the whole of psychoanalysis,” according to Joseph Breuer, Freud’s older colleague, collaborator, and co-author of his first major book, Studies on Hysteria, published in 1895. Anna, whose actual name was Bertha Pappenheim, came from a wealthy, Jewish, bourgeois family (ibid., pp. 101–106, 132–133; Gay, op. cit., pp. 63–69). Freud remarked that she was a young woman of exceptional cultivation and talents, charitable and clever. She had consulted Breuer some years beforehand after the death of her father, a man whom she dearly loved and to whom she was devoted during his final illness. Subsequently Anna became increasingly weak, anorexic, and paralytic. Among the many alarming symptoms, she alternated lethargy and excitement, “saw” skeletons and black snakes, and manifested two different personalities, one charming, the other unruly. Breuer visit ed her every evening. He encouraged her to talk freely about anything and everything. When she did, he found that her terrors diminished. She described this process as “the talking cure” or “chimney sweeping.” We might say this that was her way of slaying demons and getting rid of emotional debris.

Then, during the particularly hot spring of 1882, Anna found that she could not drink water, even though she was very thirsty. Breuer helped her enter a hypnotic state during which she recalled an incident when her English companion allowed her dog to drink out of a glass. Along with the memory, Anna reexperienced the tremendous disgust she had felt at the time. The result of this emotional catharsis, as Breuer put it, was that her hydrophobia disappeared. He repeated this again and again with her other symptoms. They too dissolved. Breuer thought he had found an antidote for mental disturbance—the release of hidden emotions. He pronounced Anna cured. Unfortunately this was not to be. She suffered many relapses, some no doubt brought about by his sudden rejection of her once he realized that she was sexually attracted to him and wanted to have his baby. Breuer could not tolerate his attraction, indeed love, for her. In any case his wife had become increasingly irritated at the time he spent with her and clearly conveyed this to him (Krüll, op. cit., p. 7).

Freud saw the sexual interplay between them. Breuer was uncertain. Sometimes he agreed that sexual conflicts lay behind mental disturbance, and other times he dismissed the notion. Perhaps a further reason for backing away from Anna was that her real name, Bertha, was the same as his mother’s. These differences resulted in a bitter conflict between Freud and Breuer and a rupture in their relations. As for Bertha Pappenheim, aka “Anna O,” she became a distinguished social worker and feminist. The German government has even issued a postage stamp in her honor.1

It is said that behind every famous therapist there lies a famous patient. For Freud this was certainly true. Although it might be better to use the word “subject” or “person,” because many of the people who contributed to his clinical practice and ideas were friends, colleagues, or even close relatives. These included his daughter, Anna; his son, Martin; Irma (Emma Eckstein?, more likely Anna Hammerschlag, the daughter of his Hebrew teacher); Emmy von N. (Fanny Moser, at the time the richest widow in Europe); Frau Cäcilie M. (Anna von Lieben); Dora (Ida Bauer); Elisabeth von R. (Ilona Weis); Katharina (Aurelia Kronich, a peasant girl); Miss Lucy R. (an English governess); Little Hans (Herbert Graf); the Rat Man (Ernst Lanzer); Enos Fingy (Joshua Wild), and the Wolf Man (Sergei Prankejeff). Other notables included the conductor Bruno Walter; the composer, Gustav Mahler; the poet, H. D., and Princess Marie Bonaparte (Fichtner, 2010, pp. 149–151).2

But the most notable man Freud “treated” was himself. And the work which most reflected his self analysis (Clark, op. cit., p. 177) was The Interpretation of Dreams, first published in November 1899. Really it was Freud’s autobiography, for so many of the dreams and dream processes he discussed were his own. Freud said the book had a powerful “subjective meaning” and saw it as “a piece of my self-analysis, my reaction to my father’s death, that is, the most significant event, the most decisive loss, of a man’s life” (Gay, op. cit., p. 89). Essentially Freud applied what he learned from “Anna O” and his other patients to himself, a method of systematic introspection and acute observation of the resistances that arose when he looked into himself. He then extended this procedure from his waking life to his dream worlds and back. In this way he saw how the unconscious mind acts, for example, through condensation (combining several thoughts and symbols into one), displacement (redirecting thoughts and feelings away from their intended recipient), repression (of forbidden desires), and dramatization (mental theater). He also observed other operations all of which served to conceal overwhelming conflicts about sex and death.

Like a master novelist, Freud compared the elucidation of dreams to a “guided tour” of the self. In a letter he wrote in August 1899 to his close friend and confidant, Wilhelm Fliess, he observed, “The whole is laid out like the fantasy of a promenade. At the beginning, [there are] the dark forest of authors (who do not see the trees), hopeless, rich in wrong tracks. Then a concealed narrow pass through which I lead the reader—my model dream with its peculiarities, details, indiscretions, bad jokes—and then suddenly the summit and the view and the question: Please, where do you want me to go now?” (ibid., p. 106).

Freud saw The Interpretation of Dreams as his “own dung-heap, [his] own seedling and a nova species mihi (sic!)” (Clark, op. cit., p. 177). Not surprisingly he was full of conflict about what to include, or leave out. “… if I were to report my own dreams, it inevitably followed that I should have to reveal to the public gaze more of the intimacies of mental life than I liked, or than is normally necessary for any writer who is a man of science, and not a poet” (p. 178). But he also acknowledged that the temptation to conceal certain embarrassing bits was very strong and that he “took the edge off some indiscretions by omission and substitutes” (p. 178). No doubt a lot of what he secreted away were his own sexual fantasies and death wishes (Gay, op. cit., p. 124). Nevertheless, he was skillfully able to uncover them in others, so much so, that he became world famous, many would say notorious, for describing a particular constellation of murderous and erotic feelings known as the “Oedipus complex.” This referred to the wish of a maturing boy to kill his father and marry his mother. The counterpart in maturing girls is the “Electra complex,” the wish of a girl to kill off her mother and marry her father. Both terms come from Greek mythology, a subject with which Freud was very familiar. He asserted that these highly emotive constellations not only occupied much of dream life, but also a large portion of people’s unspoken thoughts and feelings.

Freud elucidated what happens inside a person’s black box, that is, his or her private, subjective space. This is something that his adversaries claimed was impossible. They insisted that all one can know about other people is how they speak and act, because only these events can be verified by external observation. Freud demonstrated that this was not the case, that people contain an intense, dynamic, complicated inner domain which they are constantly trying to share with others. In so doing he wrote with the flourish of a novelist and poet, but also systematically with the discipline of a scientist.

Initially Freud gained renown as an anatomist, being the first person to dissect the testicles of an eel (ibid., p. 32). Subsequently, he devised a new method for staining sections of the brain, elucidated the structure of the medula oblongata (the back part of the brain to do with breathing and circulation), and made major contributions in neurology, particularly to do with aphasia, the inability to use or understand words (Clark, op. cit., pp. 56, 75, 109). His book, On Aphasia (1891b) remains a seminal study of the condition.

These undertakings arose within the context of nineteenth-century science which emphasized measurement and verification. Not surprisingly, Freud, the natural scientist, looked for palpable facts to support his developing theories. By the spring of 1895 he was consumed by a new undertaking, to elaborate a “Psychology for Neurologists,” which he eventually called “The Project” (“A Project for a Scientific Psychology”, 1950a). In it Freud tried to describe mental functioning in the language of classical physics and cerebral physiology. He foresaw the time when psychological functions could be described by “the amounts of energy and their distribution (or ‘discharge’) in the mental apparatus” (Gay, op. cit., p. 79). In other words he aimed “to represent psychical processes as quantitatively determinate states of specifiable material particles, thus making those processes perspicuous [i.e., lucid] and free from contradiction” (Clark, op. cit., pp. 153–154).

To begin with, Freud was elated with the manuscript, but he quickly decided it was a nonstarter. It did not explain what he hoped to know in objective terms. Even so, this thinking permeated his formulations (such as the buildup and release of sexual energies). He never gave up the idea that psychological functions might have a material basis (ibid., 155).

Above all Freud was ambitious. He lobbied prominent colleagues and journalists to have his books reviewed. He continually pressed influential friends and patients to intervene with the Austrian Ministry of Education to have his status upgraded, first to Privatdozent (lecturer), then Professor extraordinarius (associate professor), and finally, twenty years later, Professor ordinarius (full professor). Apparently the price of his first professorship was a valuable painting given by the family of Frau Marie Ferstel, a patient and wife of a diplomat, to the Minister of Education (ibid., pp. 208–210).

These efforts were consistent with Freud’s relentless determination to “spread the gospel” about his work and theories. He once confessed to Fliess, at that time a confidant, “I am actually not at all a man of science, not an observer, not an experimenter, not a thinker. I am by temperament nothing but a conquistador, an adventurer … with all the inquisitiveness, daring and tenacity characteristic of such a man” (ibid., p. 212). The resistances he encountered had to do with his theories of sexuality, which the Viennese found shocking, and anti-Semitism.

At the turn of the twentieth century Vienna was a world center for Jew hatred led by its populist mayor, Karl Lueger. He proposed, for example, that all Jews should be crammed into ships and sunk without a trace. Almost certainly Freud was passed over for academic appointments due to his Jewish background. In the circumstances one might have expected Freud to convert to Christianity in order to further his ambitions, as many of his associates had done. Yet Freud strongly retained his Jewish identity. He insisted, “My parents were Jews and I too have remained a Jew myself” (Gay, op. cit., p. 6). Among his heroes were Joseph, the dream interpreter, the son of Jacob, and Moses, who led his people into the Promised Land. As if to emphasize these attachments, he refused to accept royalties from any of his works that were translated into Yiddish or Hebrew (ibid., p. 12). Yet, at other times, he went to great lengths to hide his Jewish knowledge and to avoid religious observance.

Freud’s mother, Amalie [Nathanson], came from Galicia, the northwestern part of the Ukraine, and a center of Jewish mysticism. Among her ancestors there were rabbis and rabbinical scholars (ibid., p. 8). Amalie was a beauty when, at the age of nineteen, she married Freud’s father, Jacob, who also had come from Galicia. By then he was a middle-aged man with two grown boys by his first wife, Sally.

Freud was their first son and was born on 6 May 1856. At the same time he was named Shlomo (in German, Sigismund, later shortened to Sigmund) after his father’s father who had died six weeks previously. Thus, Freud was born into a house in mourning. This was a major factor in his life, and especially, in his relationship with his father which varied from affection to hostility. Surely, this ambivalence reflected Jacob’s uncertainty toward his own father, Shlomo, and the clash with the Hassidic culture of his childhood.

Hassidism, a mystical and religious renewal movement, began in the eighteenth century in the Ukraine and southern Poland and, within a few generations, it spread to other parts of Eastern Europe (Poland, Rumania, Hungary). Hassidic teachings are rooted in the esoteric or concealed dimension of Judaism, specifically the Kabbalah, the Jewish mystical tradition, as expounded by Rabbi Isaac Luria (the Ashkenazi Rabbi Isaac, or ARI) about 500 years ago. The Hassidic movement itself was founded by Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer, known as the Baal Shem Tov (Master of the Good Name) 200 years later. He revolutionized Judaism by reintroducing the powerful imagery of Lurianic Kabbalah in conjunction with an everyday language that could reach the most uneducated person. The Baal Shem Tov emphasized a direct, heartfelt relationship with God that touched every aspect of life through prayer, study of the Torah (the first five books of the Bible), and inner contemplation. His followers were known as hassidim, Hebrew for the “pious ones.” The opposing group of religious Jews who did not accept this direction were known as mitnagdim, which is Hebrew for “opponents.” The mitnagdim practiced a dry, scholastic, “establishment” Judaism and looked upon their Hassidic brethren as heretics. They often instigated pitched battles which resulted in many injuries and fatalities. At the least the mitnagdim (opponents) would denounce their fellow Jews to the police as traitors, whereupon they could be jailed and tortured.

By the 1800s a third force, the Haskalah or “enlightenment” arose in Germany, Austria, and other areas with large Jewish populations like Galicia. Its followers called themselves maskilim (“enlightened ones”) and encouraged their compatriots to give up the yoke of religious practice and immerse themselves in the secular world. Many Jews saw this as a small price to pay for overcoming the hatred of the gentile world and gaining professional advancement. These three groups feared and vehemently opposed each other.

Even before Sigmund was born, the Freud family was caught up in this struggle. His father, Jacob, his grandfather, Shlomo, and his great grandfather, Ephraim, were all hassidim. But around the age of thirteen, at the time of his bar mitzvah, Jacob began to break away from religious strictures by traveling widely and learning the ways of the non-Jewish world. Unusually for a man with his background, Jacob had three marriages. His firs...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Introduction

- Chapter One Sigmund Freud and the Rebbe Rashab

- Chapter Two A tale of two orphans

- Chapter Three The Jewish mystical traditions

- Chapter Four Bion and Kabbalah

- Chapter Five On the nature of the self: and its relationship with the soul

- Chapter Six On the nature of the soul: and its relationship with the self

- Chapter Seven The replacement child

- Chapter Eight Sigmund Freud and Rabbi Safran

- Chapter Nine On opposites

- Chapter Ten Lowness of spirit

- Chapter Eleven Reparation

- Chapter Twelve Atonement

- Epilogue

- Glossary of Hebrew and Yiddish Terms

- Notes

- References

- Index