![]()

Chapter 1

Why Software Value?

The head of a large software development group in a major international corporation asked me, “ How do I answer the questions from my peers in the business units about how much value I have delivered for them lately?”

If there were a single, largest driver behind the writing of this book, it would be this real-life question. It’ s a simple question, but the answer is multifaceted and, hence, complicated. Perhaps that is why so few organizations even attempt to track software value? In this chapter, I will define what I mean by the term business value of software (I will use this term and the term software value interchangeably), and I will demonstrate how businesses are suffering through their inadequate management of their software value assets and flows.

Why Not Information Technology Value More Generally?

Most people working in large corporations probably think that their software is just a standard part of the services that their information technology (IT) department provides to facilitate the organizations’ operations. Traditionally, IT departments have been cost centers in the enterprise, sometimes treated as pure overhead, but more often funded in part or wholly by charge backs from the business units. People in business units looking at this arrangement can be excused for focusing on the business value of IT. Indeed, we wrote a book with that title (Harris et al. 2008), which contained a series of questions that the business should address to the chief information officer (CIO) to ensure that the business value of IT is maximized. A fair criticism of (or compliment for) that book was that there was a disproportionate focus on software. I am unapologetic because, in my opinion, software represents the best and biggest way to increase value from today’ s IT, as hardware becomes more and more commoditized. In their book, The Real Business of IT , Hunter and Westerman (2009) reported on a survey of 153 senior executives conducted by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’ s (MIT) Center for Information Systems Research (CISR), “of the eighteen common IT and non-IT tasks, only four – application development; business process redesign and organizational change; need identification; and IT oversight – have a statistically significant correlation to the business value provided by IT.”

This book is a double acknowledgment that we did not focus enough on the business value of software in the last book and that the thinking about and tools available for software value have moved on.

Of course, the rest of IT has moved on too since we wrote the last book. The latest digitization wave (I am old enough to remember several of these) is based upon the collective challenges presented to IT departments by social media, mobile smartphones, business analytics (sometimes called “ big data” ), and cloud hosting of applications and data. Collectively, these driving forces are sometimes referred to as SMAC . Leaving aside analytics for a moment, the real industry challenge is that these trends represent significant changes for the IT departments that previously had direct control (and often ownership) of the computing hardware that staff and customers are using. Sort of. Some perspectives on this follow:

■The movement to cloud computing— essentially, renting the hardware that the software runs on— is not revolutionary because mainframe computers worked, and still work, that way. The key change here is the continuing movement from centralized hardware to decentralized hardware.

■Social media is equally driven by this hardware decentralization because the real-time, personal nature of the interactions is encouraged by the ready, real-time availability of the communication medium, seemingly no matter where you are or what you are doing!

■Mobile computing, in its basic form, covers most of the world through the wide availability of phones. Sophisticated mobile computing through smartphones covers most of the rich and corporate world. The rapid proliferation of mobile phones and then smartphones around the world is the embodiment of the decentralization of processing power that has driven attention on the opportunities (many) and threats (some) of the latest wave of digitization.

Returning to analytics, I consider the growth of analytics to be an effect rather than a cause of the decentralization of hardware. The way that people interact with their retail, banking, and other business environments has changed due to hardware decentralization. Organizations faced with interacting less with their customers in traditional environments (e.g., stores and bank branches) needed to understand how to best fulfill, make money from (or spend less on), and predict the future of these new interactions. The way that organizations have addressed these needs has matured over time according to priority. First, transactions needed to be fulfilled. Second, transactions needed to be economically viable. Finally, analysis (analytics) of transactions were needed in attempting to predict and optimize the future. Fortunately, the software and data needed to drive the transactions with the decentralized hardware were exactly what was needed to enable the analytics to try to predict future trends. Of course, collecting the data brings its own challenges, as personal privacy becomes an issue. I will consider the value of the data associated with the software in Chapter 4.

The impact of the continuing decentralization of hardware will not end with this current wave of digitization. The SMAC acronym does not take account of the Internet of things , essentially the decentralization and proliferation of Internet-capable monitoring and control capabilities to everything that is economically worth measuring in our environments, from the refrigerator door to the water flowing out of the shower.

While the preceding perspectives illustrate how our perception of IT value is changing due to hardware decentralization, there is a small counterflow that is worth noting. While cloud computing enables the distribution of processing hardware to be closer to the markets where it is needed, some software that had previously been distributed to personal computers (PCs) is being consolidated into software-as-a-service (SaaS), products of which the most often quoted example is the customer relationship management (CRM) service provided by Salesforce.com. Another more consumer-oriented example is the delivery of video on demand through Netflix. However, this software consolidation may be the exception that proves the point because I assert that SaaS implementations tend to make the software more pervasive as it usually becomes more accessible (no distribution of disks and complicated installation) at a lower cost.

My point here is that if the typical organization’ s IT department is about delivering hardware, software, and the connections between the two, then, while it has been said before but has never completely come about, I would argue that one side effect of SMAC is the increasing commoditization of the hardware in the hands of an organization’ s staff and customers. The response from organizations has been to manage this loss of control of the hardware through more and different software.

Hence, I argue that the business value of software has increased and has become relatively more important in the IT sphere than when we wrote our last book. In arguing this point, I recognize that the distinction between hardware, software, and systems is becoming smaller every year. I could have used systems throughout this book in place of software, but I felt that this would be too much of a distraction. If you prefer to read software as systems throughout the book, please be my guest.

Regrettably, the measurement of software value in organizations is sporadic and weak. As we will see in the rest of this book, there is a lot of opportunity to improve, more than enough to justify the focus of this book on software value.

Who Should Care about the Business Value of Software?

The easy answer is everyone. But let’ s dig a little deeper. In this book, I will argue for two different perspectives of the business value of software: maximizing software asset value and maximizing the flow of software value.

Software asset value must get the attention of the upper echelons of the organization, starting with the chief executive officer (CEO) and the chief financial officer (CFO) but also including the heads of business units and, much more so than it does today, the board!

But who should care about maximizing the flow of software value? It would seem obvious that “ all the above” should care because if there is no flow of new software value into the software asset pool then surely the value of the software asset pool must simply decline over time. Currently, there are few organizations whose board, senior management, and business unit heads are sending strong signals to the IT department to maximize the flow of software value. Perhaps they assume there is no need because, again, “ isn’ t it obvious?” Unfortunately, over many years, other signals from senior management have been so strong that business value is not the first thing that many development teams and development managers think about. Today’ s priorities are more likely to be

■Deadlines (often unrealistically imposed)

■Cost

■Staff utilization

Reinertsen (2009) has shown that product development, focusing on these priorities, especially in a localized way as is typical, does not maximize the flow of software value. Instead, the value (or relative value) of software programs and projects or epics and stories needs to be made explicit from top to bottom of the organization so that everyone who can influence the flow of software value is explicitly aware of the impact that their day-to-day, tactical decisions will have on the flow of software value. This, then, is a better definition of why “ everyone” should care about the business value of software.

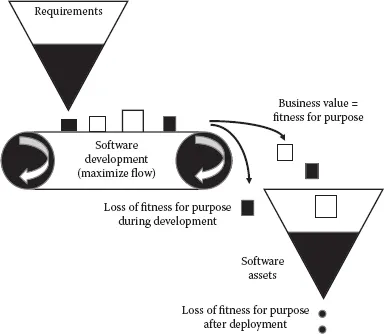

Before I leave this section, I should return to an assertion I made previously but did not justify. I claimed that, “ the value of the software asset pool must simply decline over time.” Here, I am not talking about the amortization of the capitalized cost of the software on the balance sheet— although that is certainly a consideration. Instead, I am asserting that the value of the current software to the business, the business value, will inevitably decline over time as the business environment changes. This is based on the assertion that software is most valuable to the business when it is fit for purpose . A static piece of software that is not evolving as the business environment evolves becomes less fit for purpose and therefore has less business value (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Value flow and accumulation of assets.

Interestingly, this leads to another conclusion: Not all new software added to the organization’ s software asset pool necessarily increases business value (see Figure 1.1). For example, there is no added value if the new software is not used (e.g., an ATM feature that cardholders never choose) or if the business environment has changed since the new software was requested and the new software is no longer relevant (e.g., a new, first-to-market insurance policy for which competitors have brought out a much better solution since the new software was requested). Hence, the value of a new piece of software cannot be assumed to be the value it was assigned when the business case for development was approved. Organizational process is needed to monitor, analyze, and manage the business value of the organization’ s software asset pool. I will suggest several such processes in this book.

What Is the Business Value of Software?

If we imagine an organization without software (yes, those things did exist), then the introduction of the first piece of software had a good chance of adding value to the business by increasing revenue or saving costs sufficient to cover the expense of buying or building the software. In short, the new piece of software had a good chance of increasing profits. Increased profits as a direct result of the introduction of a new piece of software is certainly the simplest form of the business value of software.

Impact of Perspective on Business Value

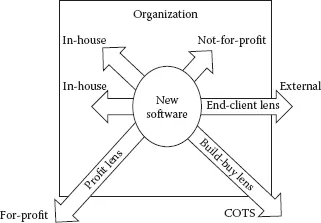

We need to acknowledge that software is viewed through different lenses at different times by different people. These lenses influence the definition of value, so it is worthwhile trying to identify some of the major ones, understanding that many organizations may contain all elements of a single lens. In Figure 1.2, I have illustrated the three main lenses that impact the business value of software perspectives:

Figure 1.2 Business value perspective lenses.

■Profit lens: For-profit or not-for-profit organization. Typically, a government agency takes a not-for-profit view of the business value of software, but that distinction is blurred if governments drive their departments ...