![]()

![]()

As the famed ethnographer Clifford Geertz (1973, p. 19) said, the qualitative researcher “‘inscribes’ social discourse; he writes it down. In doing so, he turns it from a passing event, which exists only in its own moment of occurrence, into an account, which exists in its inscription and can be reconsulted.” Writing events down transforms the fleeting into the permanent.

The need to capture moments happens throughout your project. Events and ideas will fly at you, fast and furiously, from the moment you invent the project until you add the last period to the finished manuscript. To successfully capture them, you must, as Geertz said, write them down. This chapter, then, aims to sensitize you to writing’s ubiquity in every phase of a qualitative project. Qualitative researchers should be writing all the time, converting participants’ lifeworlds (and researchers’ experiences of them) into language so others can access them. At the end, I also discuss just what characteristics make all this writing particularly qualitative.

Writing throughout your study

When to write? A complex question with a simple answer, which I’ve embedded in the chapter’s title. One writes constantly in qualitative research. When you get the lightning strike of the idea, “Golly, that would make an interesting study,” write it down. Don’t sleep on it! If you’re like me, by the time you wake up, it’ll have disappeared. “Future You” – the person you will be when later writing your report, article, or dissertation – needs the information written down. Maybe keep some sticky notes by your bed and record the ideas. Jot things on your mobile phone or keep a paper notebook in your pocket. Whatever it takes to immortalize the study’s progress and your growing understandings. From that first moment on, through the next million tiny tasks that your study involves, you will produce reams of writing about how the study changes, sharpens, and moves into the public sphere. The following moments feature writing prominently, many of which I further elaborate in subsequent chapters.

Planning and managing the study

Even before you start conducting interviews and observations, you have much to write. Planning and managing the million steps involved in completing a study happens through reminders to yourself as well as proposals to others. Before you finally leave home with your voice recorder and field notebook to do your first data collection, you’ll hopefully have written extensively about your goals, explored your subjectivities, composed funding and/or thesis proposals, filled out ethics applications, and created and crossed off numerous to-do lists.

Correspondence

Qualitative research almost always requires the participation of other people. Even historical, archival work usually requires you to interact with an archivist. For most qualitative researchers, one interacts with others to help recruit participants, to get data about participants’ lives, to read our drafts, to approve our degrees, to fund our work, and so much more. Not every interaction happens in person or on the phone – indeed, increasingly less as life becomes digital – but often happens via writing. Qualitative researchers constantly write to participants, peers, and other professionals, whether sending text messages informing interviewees when they are running late, internet chatting with a librarian to help find a reference, emailing participants for reactions to interpretations, or setting up a dissertation defense time. In doing so, one constantly shows her writing to participants and those who help her with the research.

That others constantly witness your writing suggests that you take seriously everything you commit to paper or screen. Your writing helps forge relationships, maintaining ethical engagement before, during, and after your study – including the important thank you notes you should be writing (said in scolding parental tone). Your correspondence writing puts your professionalism on display, establishing your credibility, your maturity, your kindness, your thoughtfulness, and whether it’s worthwhile to help you. Not to paralyze you with self-doubt, but take even the little messages seriously.

Fieldnotes, interview notes, artifact analysis notes

Good qualitative methods involve you corresponding with yourself, too. Throughout your study, when writing fieldnotes, notes about interviews, and notes about documents or artifacts (and memos, discussed in the next section), you communicate to Future You. You might think, “I’ll just jot a word or two now. I’ll remember it later when I write the final draft.” Yet you may not come back to that short note for weeks, months, or even years, and by then you won’t have any idea what you meant. Record details, explicate what you mean, and avoid shortcuts. Write as if to a stranger, because the sands of time wear away memories of even momentous events.

On the topic of writing fieldnotes, I cannot improve upon the work of Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw (2011), either for examining fieldnotes’ purposes or the mechanics of composing them. I commend their book to every qualitative researcher doing observational work. Fieldnotes form the foundation of one’s entire project, for

Thus, fieldnotes house both memory and interpretation, the reconstruction of a world you experienced and will later convey to your reader.

Though researchers share them less – or perhaps don’t record them at all – interview notes and document or artifact analysis notes also help with reconstructing your study. Taking time to record the periphery of an interview, not just the words said but also body movements, emotional tone, interruptions and more, preserves key aspects for later analysis. Similarly, beyond just coding copies of documents or photos of artifacts, recording their provenance, how you located them, their shape and texture and condition, and how others use or treat them preserves key information you may need later, both for analysis and perhaps for writing actual sections of your report.

Writing memos

Memos involve, as you might know, making frequent reflective notes about various aspects of a project (e.g., Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Memos feature reflective writing done outside the heated, hyper-focused moments of data collection, looking back at data to make sense of it. Birks, Chapman, and Francis (2008, pp. 70–72) suggested that memos can perform functions like “mapping research activities,” “extracting meaning from the data,” “maintaining momentum” in analysis and theory development, and “opening communication” when working in teams. Recording developing thoughts in memos helps Future You see, months or years into the project, how ideas have sharpened and changed over time. You can revisit your initial forays into the site, the crucial things you were ignorant of (as any novice would be), and how you grew more informed. You can recall the people or moments that helped you integrate into the setting and the watershed events that illuminated the culture or process studied.

Take, for example, this passage from Barrie Thorne’s (1993) ethnography of gender dynamics in play at school, reflecting on how she decided whether to intervene when students misbehaved:

Such moments feel like Thorne based them on deep engagement with both fieldnotes and memos. From the fieldnotes she perhaps pulled the events – swearing, blowing bubbles, admitting shoplifting – but from her memos likely came the emotional memory of being “elated,” “reassured,” “detached,” “felt … on one side.” You can sense that memos were behind her perception of role shifts and acceptance across time. Obviously, I cannot know whether memos served that function, but it seems unlikely that Thorne’s initial fieldwork from 1976 and 1980 would be fresh enough in mind to write a book published in 1993 without detailed notes from which to work.

Though some may worry that constantly memoing will prove a waste of time in the end, that only the last ideas go into the final reporting, in fact memos from every project stage are useful. Early fieldnotes and memos can show readers how your thinking and methods evolved; you can quote from these documents in your report, pointing out how more time or shifts in methods clarified early mis- or half-understandings. Re-reading early notes during analysis can remind you of tiny events you had forgotten, sending you through the data again to mine new veins of interpretation.

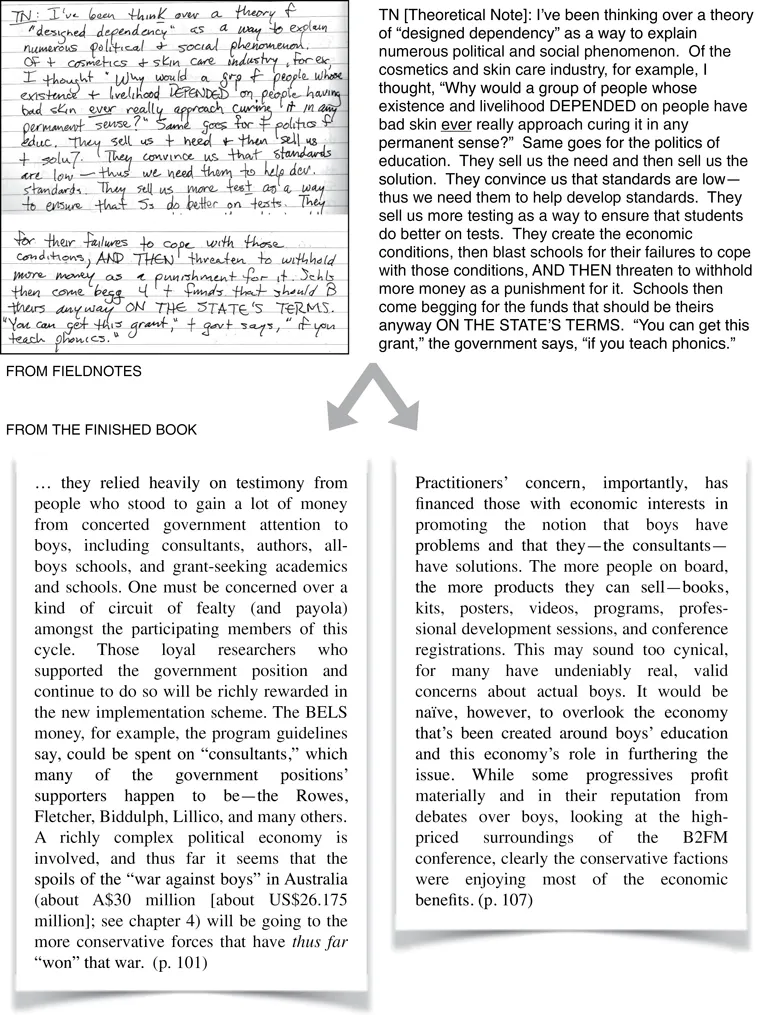

Consider, for example, the material in Figure 1.1, a brief memo I wrote in my field notebook, probably while coming home on the train. Other notes about books I had been reading surrounded it, perhaps influencing me to mull over the competing interests I wrote about. Originally the state’s role in creating things to buy interested me, but later reflections built on this insight to consider how scholars and educational service providers profit from conditions they create or stoke. All stemmed from that early note, and it evolved to cover even more cases and actors in later memos.

You never know when and how you’ll need notes, so make as many as you can. I have never regretted time spent writing notes I haven’t used, but I have many times rued not having notes about something when I needed them.

Analyzing data

Coding – the most common form of qualitative data analysis – naturally involves writing, for the analyst chooses words that provide the “right” connotation or “feel” for the data. Well-chosen words for a code can illuminate the concept, bringing clarity to one’s perception of the whole topic. Hastily chosen words or the wrong metaphor, conversely, can cement a bias into one’s coding. Take another example from Thorne (1993). She noted that what she called the young people – whether “children” or “kids” – made a significant difference to her analysis process.

Such a seemingly simple choice of words – one I have made thousands of times without a second thought – became for Thorne a moment of insight to avoid imposing “adult-ideological” ways of seeing her participants’ world. What similar terms do you use that cloud your insights with power dynamics or stereotypes?

As noted already, analyzing data often involves using memos. As Glaser and Strauss (1967) demonstrated in their original work on grounded theory, memos help researchers move from coding, where one identifies concepts and categories, toward theory, where one establishes how those concepts and categories relate. Writing memos provides opportunity for “thinking on paper,” a means of seeing what you know so you can explain it to someone else. Memos often provide a means of doing that, but so too does the free writing Becker...