I begin the writing of this book not in my office. It’s August, and my office is on vacation. Nonetheless, although I temporarily stopped seeing patients for 50-minute sessions in my room on West 82nd Street, I had not fully vacated my position. The psychoanalytic office does not exist apart from the office of the psychoanalyst, and these two are somewhat analogous to the White House and the office of the presidency. A president is not always in the White House but never stops occupying the office while on the job, and even, to some degree, remains in office even after leaving the White House.

In classical Greece and Rome, early office holders literally carried their work with them. Being the holder of an office meant having authority and responsibilities and carrying out the traditions attached to a particular role. The movement from carrying an office to occupying a physical space in which an anointed one carried out an office’s responsibilities first occurred in monasteries. Monks and nuns held religious offices and often worked in private cells to fully concentrate on their prayer and studies. During the Renaissance, the offices of artists and intellectuals were the studio, the study, and the atelier. Returning to the example of the office of the president, we have seen quite recently how an office holder may fall far short of their duties and responsibilities. Not all who have sat in the Oval Office at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue have done it justice. Occupying space is not the same as occupying an office or being occupied by an office. To isolate oneself in an independent space for an enlightened purpose is at the heart of every psychoanalytic office, whether it is a private room of an individual practitioner or a private space in a university center or a hospital clinic. The professionals in these rooms are holders of the psychoanalytic office.

My early roots prefigured my occupation with the psychoanalytic office, beginning with an interest in my father’s exemplary office in which he served as a Certified Public Accountant. He occupied a number of professional spaces during my childhood, but the office I most associate with him was on 161st Street in the Bronx, a few short blocks east of old Yankee Stadium, in a large commercial building. The heavy wooden door at the entrance to his office had a panel and transom of smoked glass. On the door, in gold-leaf stenciled letters, were the words Leo Gerald, C.P.A.

I have been occupied by the psychoanalytic office for almost 50 years now, since I stepped into my first therapist’s office in the magnificent Lewis Morris building on the Grand Concourse. The sensory associations with that visit are deeply held in the recesses of my unconscious. One of the most impressive of the splendid Art Deco buildings that lined the boulevard dubbed “the Champs-Elysées of the Bronx,” the Lewis Morris in those days had a spacious lobby and a long listing of offices. Searching for Dr. Bloom’s listing and office, I was filled with anxiety. I carried the dissociated experience of death that had been all too close, and at the same time, the anxious anticipation of relief from the dread of my own existence. It was 1969, and the war was raging in Vietnam; many of my friends were in the throes of addiction, and I myself was floundering. Dr. Bloom proved to be a solid, unflappable presence. He was a large man with a mustache and thinning hair, and he wore glasses. I don’t remember much else about his appearance or his office accoutrements. Perhaps there was a couch I sat on. The room was smallish, giving me the impression of a secure space in which I could speak openly under Dr. Bloom’s attentive gaze. I saw him for about six months and attribute to those weekly sessions my release from paralyzing dread. I also gained the strength to leave New York City and begin my dream of a California life.

These offices of my father and Dr. Bloom and the rooms of my childhood, both real and metaphorical, are the context of my own psychoanalytic practice and my office and how I both possess and am possessed by the psychoanalytic space. It is my contention that all psychoanalytic offices are created from the material of the unique spatial templates internalized in early life by each practitioner. Moreover, alongside this fundamental contribution to analytic space is the lasting influence of the progenitor of the psychoanalytic office, Sigmund Freud’s rooms at Bergasse 19 in Vienna, Austria.

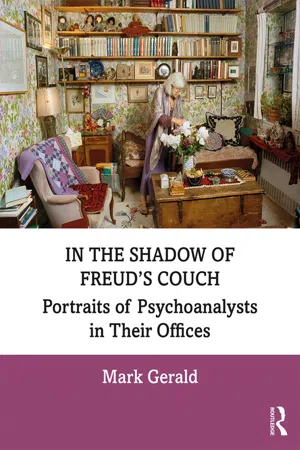

As a photographer, I have visited psychoanalytic offices in various regions of the United States and in Canada, Mexico, South America, the United Kingdom, and continental Europe, where I have invariably found unmistakable replications (sometimes quite subtle) of Sigmund Freud’s iconic office. Despite cultural, theoretical, and personal idiosyncrasies, the shadow of Freud’s couch remains.

Historians of Freud’s office

We are indebted to two marginalized figures for having memorialized that first office of the father of psychoanalysis – August Aichhorn and Edmund Engelman. Aichhorn possessed a prescient understanding of the importance of that iconic space at 19 Bergasse, and he was determined that it would not be lost to history and posterity. It was Aichhorn who recruited the young photographer Edmund Engelman to document the birthplace of psychoanalysis.

Aichhorn was a person of unique gifts and moral courage. An educator, clinician, and theorist in the area of juvenile delinquency, he trained in Vienna. Despite his relative obscurity, Anna Freud (1951) wrote in his obituary that “he was destined to become one of the significant figures of the psycho-analytic movement” (p. 51). Aichhorn had a calm self-confidence that remained unshaken by the impact of his young delinquents and criminals, and he was not deterred by the attacks of hostile government officials (A. Freud, 1951). His empathic identification drew him to work with adolescents whose behavior was antisocial and lawless, and his innovative schools for these young people used creative modifications of classical psychoanalytic techniques. Aichhorn felt comfortable with this marginalized segment of society – these children who did not fit the mold for “the analyzable patient.”

Although Aichhorn was not Jewish and therefore was exempt from the dehumanizing Nuremberg laws, he was connected with the marginalized people these laws targeted. The Nuremberg laws stripped German Jews (and later the Roma and anyone considered “racially suspect”) of their citizenship, severely limited their ability to practice medicine and law, required they register with the government based on arbitrary hereditary determination, and prohibited their intermarriage with so-called Aryans. Psychoanalysis was labeled a “Jewish science” because both Freud and many early psychoanalysts were Jewish. Aichhorn was especially close to Freud and his daughter Anna, but more important, he possessed an uncommon understanding of the historical significance of Freud’s work. As Aichhorn’s earlier pioneering work in delinquency indicated, he was a man ahead of his time.

Aichhorn, a member of the liberal Social Democratic Party in Vienna, met and befriended Edmund Engelman, a young photographer, through their mutual political affiliation. Engelman’s part in preserving the history of the psychoanalytic office can be seen as equally propitious and fated. Engelman was the proprietor of a well-known photography studio and store in central Vienna. Although 50 years Freud’s junior, Engelman grew up in the same neighborhood as the father of psychoanalysis, and the two men attended the same high school (Werner, 2002). Engelman, like Freud, came from a middle-class family of non-observant Jews. He was trained as an engineer, but as with Freud’s training as a neurologist, his employment opportunities were restricted by anti-Semitism. As a result, Engelman became a photographer. In 1934, he documented the devastating impact of the Austrian government’s crackdown on a workers’ strike against fascism (Werner, 2002). The Vienna housing projects where the workers were barricaded were bombed and destroyed, resulting in the homeless women and children being captured by Engelman’s camera. When the Nazis invaded Austria, Engelman destroyed the negatives for fear that, if found, they would incriminate him as an enemy of the Third Reich (Engelman, 1976).

Perhaps Engelman undertook the project of photographing Freud’s office, which involved substantial personal risk, as the Nazis held Freud’s quarters under close surveillance as a gesture of reparation for the lost 1934 photographs. Documenting the birthplace of “the Jewish science” was forbidden by the authorities, yet Engelman became the courageous recorder and preserver of psychoanalysis. In May 1938, 30-year-old Engelman entered the apartment building at 19 Bergasse with minimal equipment, using simple lamps and natural light to photograph the 82-year-old founder of psychoanalysis in his surroundings.

In the summer of 2001, I was in Vienna for a few days and visited Freud’s office. This was my first visit to Austria, and I knew the city’s association with Mozart, Beethoven, and of course, Sigmund Freud. But I also associated Vienna with the Anschluss of the Third Reich. Prior to leaving New York, I had spent some time speaking with my sister’s friend, George, a Viennese Jew who had emigrated to the United States as an adolescent early in 1939. He had served in the United Sates military and was a very patriotic American. He shared his memory of Kristallnacht, the “Night of Broken Glass,” a state-sanctioned pogrom that took place in Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland. Jewish homes, schools, businesses, hospitals, and synagogues were destroyed, and many Jews were beaten, arrested, and murdered, while some 30,000 men were arrested and deported to concentration camps. George had never returned to the city of his youth, but Vienna remained a burning center of fear and rage in this otherwise mellow octogenarian.

His recollections were somewhere in the back of my mind as I strolled through the elegant Hotel Sacher lobby where I was staying and toward the concierge. I asked directions to the Freud Museum, and my inquiry was met with a puzzled expression on the face of this staff member, whose job it was to guide guests to places of interest or note in Vienna. I thought at first that he did not understand my question and thus attempted to repeat it in halting German. But the concierge’s response, in clear and articulate English, confirmed that he did not know where the Freud Museum was located and hardly knew it existed. This remarkable and disturbing experience was heightened moments later when I stepped out of the hotel and immediately came upon the Monument Against War and Fascism.

In a plaza near the great opera house are four sculptures with antiwar and antifascist themes. I particularly noticed the figure of a bearded man with a toothbrush, hunched over in subjugation and humiliation. The sculpture memorialized a historical incident occurring in Austria, when Jews were forced to clean up anti-Nazi graffiti during the Hitler era. I found it ironic that this city, despite its repudiation of its infamous past, appeared to retain an indifference to the lessons of history, as evidenced in the concierge’s ignorance.

This question of indifference accompanied me on my visit to Freud’s office. What I found when I got to my destination were Engleman’s images in the preserved architectural space. Most of the furnishings and objects were removed from the original office and are now in the Freud House in London. Engelman’s photographs, which were not reproduced and made available until 1976, show the iconic psychoanalytic office in great detail. These images have loomed over all subsequent psychoanalyst offices worldwide, and indeed, they loomed in their imaginative form even before they became widely available. Engelman’s experience during the three days of photographing Bergasse 19 is recorded as “A Memoir” in his book of the photographs (1976). Engelman and Aichhorn were in agreement about making an exact photographic record of every detail of Freud’s office “so that … a museum can be created when the storm of the years is over” (Engelman, 1976, p. 134). What Engelman found at Bergasse 19 was a museum in itself, according to Fuss and Sanders (2004), two scholars who, along with others (e.g., Gerald, 2011; Werner, 2002), have teased out some important themes from Engelman’s work. “Wherever one looked, there was a glimpse into the past,” Engelman himself noted (1976, p. 138). Freud’s collection of antiques were dominated by death-related objects, and the room was crypt-like, a place “of loss and absence, grief and memory, elegy and mourning” (Fuss & Sanders, 2004, p. 79).

Thus we must start with Freud to understand the psychoanalytic office, the first office holder, whose influence continues to permeate every psychoanalytic office even today. Freud died in London in 1939, a little more than a year after he left Vienna. His dying, at age 83, was protracted over a period of a few weeks. Freud had made a pact with his personal physician, Max Schur, when he treated him for mouth cancer in his early 70s: Schur promised his friend and patient that when the time came, he would help him to die. Schur kept his agreement with the aid of morphine, and Freud’s death with dignity was a credit to analysis (Roiphe, 2016). But Freud’s relationship and preoccupation with his own death began when he was still a relatively young man. Freud, the great rationalist, was susceptible to superstitious beliefs, what he termed “specifically Jewish mysticism” (Gay, 1988, p. 58). He predicted his own death on a number of occasions, imagining himself dying more than 30 years before the actual event.

The importance of his preoccupation with death, or what Freud termed his “death deliria,” and its relationship to the psychoanalytic office are cogently developed by Diana Fuss’s edited volume, The Sense of an Interior: Four Writers and the Rooms that Shaped Them (2004). In her chapter on Freud, written with architect Joel Sanders, she makes the case that much of classical psychoanalytic practice is based on Freud’s avoidance of looking closely at death. The authors also argue that hearing is privileged over seeing in the design and architecture of the iconic psychoanalytic office. Using Engelman’s photographs and architectural drawings of Bergasse 19 as a basis for their argument, Fuss and Sanders (2004) describe their own exploration of this space as “an attempt at recovery, at reconstituting from the fragments of history what has been buried and lost” (p. 73). This act of mourning comes from the same place as the “memorialization that so pervasively organized the space of Freud’s office” (p. 73). Following the death of his father in 1896, when Freud was 40, he began to put together what became his collection of more than 2,000 antiquities, or exhumed objects: Etruscan funeral vases, bronze coffins, Roman death masks, and portraits of mummies.

Fuss and Sanders (2004) build a case for the presence of “survivor guilt” in Freud’s office and quote from a letter Freud wrote in 1894 to Wilhelm Fliess, the person who may have been something like an analyst for Freud (Gay, 1988, p. 58). Freud indicates that although he has no scientific basis for his prediction, he “shall go on suffering from various complaints for another four to five to eight years, with good and bad periods, and then between 40 and 50 perish very abruptly from a rupture of the heart” (Freud in Gay, 1988). Freud lived another 45 years after this letter to Fliess, but his father Jacob died of coronary disease shortly after his prediction. Fuss and Sanders say, “Freud apparently felt that his father died in his place, prompting a labor of self-entombment that exhausted itself only with Freud’s own painful and prolonged death almost a half a century later” (2004, p. 79).

The museum–mausoleum that was Freud’s no longer exists as a working office. To pay homage to the master, people visit the original space in Vienna or the house at 20 Maresfield Gardens in London, England, where Freud lived for a year after leaving Vienna. The two spaces together convey something essential of the psychoanalytic office, its duality and the presence of loss. The theme of death and loss is prominent in the story of the psychoanalytic office, where the psychoanalytic discipline developed in both theory and clinical practice. Nowadays the psychoanalytic office has been decentralized from central Europe to England, South America, the United States, and various other parts of the world.

Although the space where analysis takes place has not received much attention in the psychoanalytic literature (Akhtar, 2009), professionals often experience strong emotions when setting up a first office, moving to a...