- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Often misunderstood, the New Towns story is a fascinating one of anarchists, artists, visionaries, and the promise of a new beginning for millions of people. New Towns: The Rise Fall and Rebirth offers a new perspective on the New Towns Record and uses case-studies to address the myths and realities of the programme. It provides valuable lessons for the growth and renewal of the existing New Towns and post-war housing estates and town centres, including recommendations for practitioners, politicians and communities interested in the renewal of existing New Towns and the creation of new communities for the 21st century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access New Towns by Katy Lock,Hugh Ellis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

THE BIRTH, RISE AND FALL OF THE UK’S NEW TOWNS

01 THE BIRTH OF THE NEW TOWNS

02 THE RISE AND FALL OF THE NEW TOWNS

03 NEW TOWN HINTERLAND

01

THE BIRTH OF THE NEW TOWNS

It is a long cry from [Thomas] More’s Utopia, to the New Towns Bill, but it is not unreasonable to expect that Utopia of 1515 should be translated into practical reality in 1946 … Our aim must be to combine in the new town the friendly spirit of the former slum with the vastly improved health conditions of the new estate, but it must be a broadened spirit, embracing all classes of society … We may well produce in the new towns a new type of citizen, a healthy, self-respecting, dignified person with a sense of beauty, culture and civic pride.

Lewis Silkin, Minister of Town and Country Planning, introducing the second reading of the New Towns Bill, 1946.1

Introduction

The New Towns programme, with its three phases, was the most ambitious town-building programme ever undertaken in the UK and has been described as ‘perhaps the greatest single creation of planned urbanism ever undertaken anywhere‘. 2

It is difficult to imagine a contemporary politician giving a speech with the same passion as that of Lewis Silkin as he introduced the New Towns Bill in 1946. But a government with the ambition to transform the nation and enable no less than ‘a new kind of citizen’ does not appear overnight. Understood as a response to the need for postwar reconstruction, the New Towns programme emerged in the wake of half a century of thinking about how we might live. This rich history, which we set out in detail in The Art of Building a Garden City,3 underpinned the postwar government’s response to the immediate drivers of population growth, deindustrialisation, modernism and the political transformation which total war had produced. In this chapter we touch on these key influences and drivers before setting out the mechanics of the New Towns Act, and the delivery of 32 new towns that followed.

Growing new towns from garden cities

The words ‘new town’ and ‘garden city’ are frequently used interchangeably when talking about new communities today but these terms are in fact two related but distinct concepts. The garden city story starts half a millennium ago with Thomas More’s Utopia,4 and there is no doubt that the New Towns programme would never have happened without the transformational Garden City Principles distilled by Ebenezer Howard.

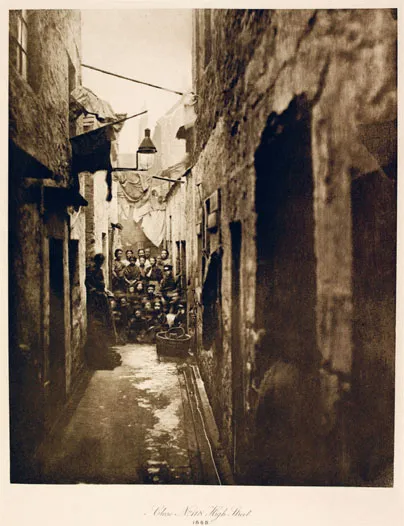

Howard’s genius lay in combining a vision of a socially just community with a key financial measure that would make that vision a reality. The garden city was not simply a design concept but an attempt to create a fair and cooperative society. These new, self-contained towns would replace slums (Figure 1.1) with high-quality housing for working people; each house would have a decent garden and generous play space for children. The garden cities would provide for the best blend of town and country, allowing not just access to the natural environment but also bringing that environment into the heart of the city. This union of town and country would encourage healthy communities, not just through physical activity and fresh air but a healthy social life. The garden cities would also have integrated transport systems and a strong emphasis on democratic community governance. Each garden city would have its own employment to limit commuting. They would be towns ‘designed for industry and healthy living; of a size that makes possible a full measure of social life, but not larger; surrounded by a permanent belt of rural land; the whole of the land being in public ownership or held in trust for the community’.5

1.1 TENEMENT HOUSING IN GLASGOW IN 1868. THE GARDEN CITY IDEA AIMED TO PROVIDE AN ALTERNATIVE TO THE 19TH-CENTURY SLUM HOUSING THAT BLIGHTED THE LIVES OF SO MANY WORKING PEOPLE.

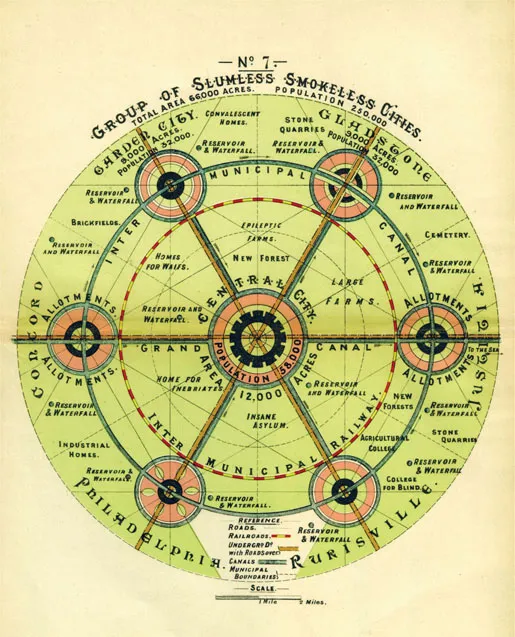

Howard did not envisage isolated communities. He set out a vision for a garden city that would reach an ideal population of around 32,000 people. Once this planned limit had been reached, a new city would be started a short distance away, followed by another, and another, until a network of such places was created, with each city providing a range of jobs and services, but each connected to the others through excellent public transport, providing all the benefits of a much larger city but with each resident having easy access to the countryside. Howard called this network of connected settlements the ‘Social City’ (Figure 1.2).

1.2 SOCIAL CITY DIAGRAM. EBENEZER HOWARD’S VISION FOR A NETWORK OF GARDEN CITIES HAD A PROFOUND INFLUENCE ON THE POSTWAR NEW TOWNS PROGRAMME.

By the 1920s, the garden city movement had already transformed the way Britain – and indeed the world – thought about dealing with urban growth and renewal.

Ebenezer Howard’s seminal work To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform (1898) led to the creation of the Garden Cities Association (now the Town and Country Planning Association) in 1899 and to the first garden city experiment at Letchworth by 1903.6

Howard’s blueprint for beautiful, healthy and cooperative new communities was revolutionary not just in the importance it attached to good planning, but in the inclusion within his model of practical ways of both paying for development and giving the community a permanent financial share in the place where they live (possibly sufficient, he thought, to provide pensions, healthcare and education, none of which were freely available at that time).

Howard’s holistic and principled vision has proved to be an elegant and durable ideal of social transformation. The concepts of land value capture, ‘marrying town and country’, community development and a spirit of innovation and experimentation were the key principles that evolved between the garden cities and new towns.

The garden city financial model

Under Ebenezer Howard’s garden city model, the land ownership (in today’s terms, the freehold) of the entire development would be retained by a limited-profit, semi-philanthropic body similar to a community interest company or trust: income earned from capitalising on the increasing land values which result from development – known as ‘betterment’ – and from residential and commercial leaseholders (with uplift on reversion at the end of lease periods) would be used to repay the original development finance debts. As these debts were gradually paid off, and as land values rose, the money could be increasingly invested in community assets and services, building up what we might think of as the garden city ‘mini-welfare state’.

The garden city idea progressed at an astonishing speed; a year after publishing To-morrow, Howard and his supporters formed the Garden Cities Association (which became the Garden Cities and Town Planning Association in 1909 and the Town and Country Planning Association in 1941). By 1903, the Association’s Garden City Pioneer Company was set up to find a site, and First Garden City Limited was formed to build the first garden city at Letchworth, Hertfordshire, designed by Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin (Figure 1.3).

1.3 RUSHBY MEAD, LETCHWORTH GARDEN CITY. EARLY HOUSING IN LETCHWORTH WAS THE EMBODIMENT OF THE ARTS AND CRAFTS DESIGN IDEALS, PROVIDING BEAUTY IN HUMAN SCALE, HOMES SENSITIVE TO THE PAST AND PRESENT, USING LOCAL MATERIALS.

But it was not a straight trajectory. Letchworth Garden City struggled to assemble enough low-interest loans for the start-up phase of capital works, and although the outbreak of war in 1914 gave a boost to the local economy (the dust-cart building company, for example, switched over to making armoured vehicles), building materials and labour were in short supply. Even so, Letchworth inspired countless developments around the world, and its cooperative spirit and socialist ideals attracted ‘every sandal-wearing, vegetarian, teetotaller’,7 an association which later the new towns tried their best to shrug.

Another key prewar moment came in 1912, when Raymond Unwin, who had left Letchworth to work on Hampstead Garden Suburb, published Nothing Gained by Overcrowding!, an influential pamphlet which set out how an alternative to bylaw terraces – the housing standard at the time – could improve the way people live.8

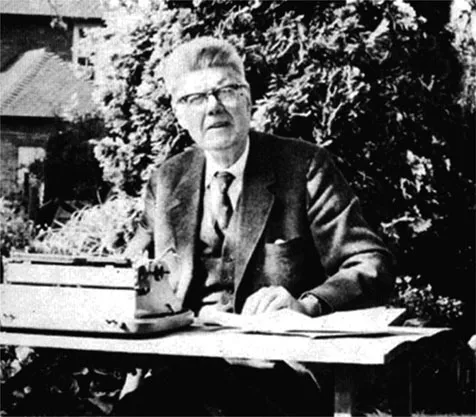

Nothing Gained by Overcrowding! was influential in the design and layout of new homes but its publication was also to mark Unwin’s second transformation, from campaigning outsider to the UK’s most influential chief planner. The year 1912 was also notable as the time when Frederic James Osborn, a former clerk, aged just 27, joined the Howard Cottage Society at Letchworth as secretary and manager. Osborn went on to be the driving force behind the postwar New Towns programme that followed (Figure 1.4).

1.4 FREDERIC JAMES OSBORN, A...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- IMAGE CREDITS

- Contents

- ABOUT THE AUTHORS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- SPONSORS

- FOREWORD

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I: THE BIRTH, RISE AND FALL OF THE UK’S NEW TOWNS

- PART II: THE NEW TOWNS AT MIDDLE AGE

- PART III: REBIRTH OF THE NEW TOWNS

- NOTES AND REFERENCES

- INDEX