eBook - ePub

Designing for Older Adults

Principles and Creative Human Factors Approaches, Third Edition

- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Designing for Older Adults

Principles and Creative Human Factors Approaches, Third Edition

About this book

Winner of the 2019 Richard M. Kalish Innovative Publication Book Award 2019 – Gerontological Society of America

This new edition provides easily accessible and usable guidelines for practitioners in the design community for older adults. It includes an updated overview of the demographic characteristics of older adult populations and the scientific knowledge base of the aging process relevant to design. New chapters include Existing and Emerging Technologies, Work and Volunteering, Social Engagement, and Leisure Activities. Also included is basic information on user-centered design and specific recommendations for conducting research with older adults.

Features

-

- Focuses on design for diverse groups of older adults

- Introduces the latest scientific advances, but is easily accessible to practitioners and students

- Offers an emphasis on existing and emerging technologies within everyday contexts and activities

- Includes many examples of everyday activities and contexts, as well as new chapters

- Presents a new conceptual model linking design principles across a broad range of topics

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Designing for Older Adults by Sara J. Czaja,Walter R. Boot,Neil Charness,Wendy A. Rogers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Industrial Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

section three

Application areas

chapter nine

Transportation

Who lives sees much. Who travels sees more.

An Arab proverb

The ability to successfully use transportation can be thought of as a “keystone” activity in that it supports the performance of many other tasks important for maintaining wellbeing and independence. Transportation allows older adults to manage their health (visit doctors, pick up prescriptions), prepare meals, and perform housekeeping (shop for groceries and cleaning supplies), maintain social connections (attend religious services, visit friends and family), and engage in leisure activities (visit parks, participate in senior center events, travel for pleasure). Inability to use transportation puts older adults at risk for social isolation, which is associated with poor mental and physical health and lower quality of life. Lack of transportation options also limits opportunities to engage in work and volunteer experiences. These negative outcomes highlight the need for a focus on ensuring safe and accessible transportation for older adults, and human factors approaches are a key component of reaching this goal.

Age-related physical and cognitive changes can make transportation challenging for older adults. Changes in vision can decrease the comfort of older drivers as well as increase the risk of certain types of crashes. Slower walking speeds can make navigating as a pedestrian – for example in a busy parking lot – more difficult and less safe. Increased susceptibility to crash forces makes the consequences of a crash more serious for older road users (drivers, passengers, pedestrians, and cyclists) relative to younger ones. Challenges extend beyond the roadway; for an air traveler, age-related perceptual, cognitive, and physical changes can increase the difficulty of all stages of air travel. This includes purchasing a ticket online, using an automated kiosk to check in for a flight, navigating to a departure gate, and retrieving luggage at the end of a trip. Should these challenges become too great, older adults may limit or cease their transportation activities all together, which can have a profound impact on their independence, health, and wellbeing.

This chapter will illustrate the relevance of previously described design principles to various transportation systems. Transportation in this chapter is broadly defined, and covers most means through which older adults move from one location to another, whether the distance between locations is small (parking lot to store entrance) or large (one continent to another). A substantial focus of the chapter will be on older road users, and specifically the older driver because the private automobile is by far the preferred mode of transportation among many older adults in North America, and most trips they complete are by automobile (about 80%). However, we also discuss important issues related to public transportation systems and wayfinding more generally (e.g., traveling by bus or train). When the infrastructure is present, navigating public transit systems can serve as a valuable supplement to, or replacement for, the private automobile as individuals age; public transportation has the additional benefit of reducing planet-warming emissions.

9.1Driving

9.1.1Older driver statistics

In the United States in 2016, there were approximately 222 million licensed drivers. This figure includes 42 million drivers 65 years of age or older (19%). The number of older drivers in the United States and around the world is expected to increase sharply over the next few decades because of population aging, making any differential crash risk older adults experience an urgent challenge to address. For example, by the year 2030, it is predicted that the percentage of older licensed drivers in the Netherlands will be greater than 26% (compared to only 14% in 2000).

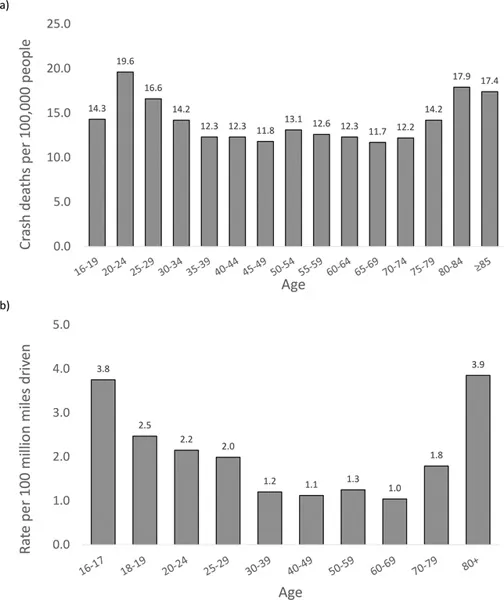

Are older drivers safe drivers? While this sounds like a simple question, providing an accurate answer is quite complex. First, the unequal number of people in each age group in the population influences the likelihood that a member of any age group will experience a crash. To account for this variation when making comparisons, the number of crashes that different age groups experience is often conditionalized on the number of people within each group in the population. Also, because many older adults are retired, they drive less frequently compared to younger drivers who may be driving to work and/or school on a regular basis. This difference means older adults’ exposure to the risk of a crash is less compared to younger adults, and can be accounted for by conditionalizing crash numbers on estimates of the number of miles driven by members of each age group. Figure 9.1 depicts individuals’ likelihood of being killed in a crash controlling for representation in the population (Figure 9.1a), and driver fatal crash involvement controlling for miles driven (Figure 9.1b).

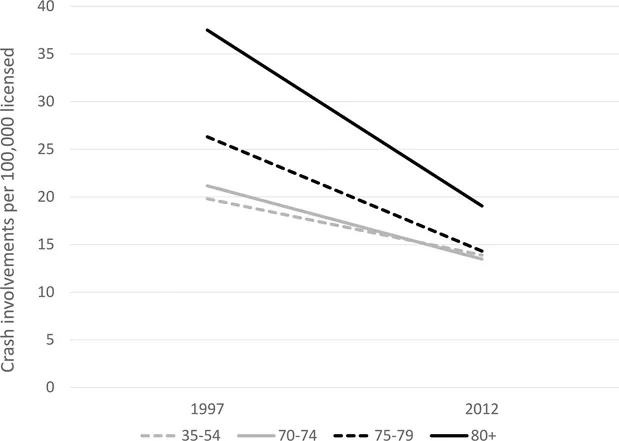

Statistics like these suggest that older drivers are at greater risk of being involved in a serious crash. But another important factor to consider is increased fragility associated with advancing age. Age-related changes in the body’s ability to handle crash forces mean that the same crash that injures a younger adult might severely injure or kill an older adult, largely accounting for differences between younger and older adults’ involvement in serious and fatal crashes. Some argue that increased fragility is the primary risk that older adults face, and that excess crash involvement plays a relatively minor role. This conclusion is consistent with a general decrease in the risk older drivers have faced over the past few decades as car manufacturers have implemented more advanced features to reduce the impact of crash forces on vehicle occupants (see Figure 9.2). In this sense, any change to the vehicle or the roadway that reduces the likelihood of a crash differentially benefits older drivers.

Figure 9.1 (a, above) Crash deaths per age group controlling for the number of people within the population (Source: 2016 data, http://www.iihs.org/iihs/topics/t/older-drivers/fatalityfacts/older-people). (b, below) Fatal crash involvement as a function of driver age per 100 million miles driven (Source: 2014–2015 data; Tefft, B.C. (2017). Rates of Motor Vehicle Crashes, Injuries and Deaths in Relation to Driver Age, United States, 2014–2015. AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety).

Despite negative stereotypes, older adults affected by normative changes in perception, cognition, and movement control in general are safe drivers. Compared to younger drivers, they are more likely to obey speed limits, wear seatbelts, take fewer risks while driving, and are less likely to drive distracted or intoxicated. They also often modulate their driving to account for normative age-related changes. For example, some older adults drive more slowly to account for age-related changes in reaction time, and avoid driving at night and in inclement weather due to age-related changes in vision. To avoid challenging left turns across an oncoming stream of opposing traffic (in countries in which drivers drive on the right side of the road), some older adults may choose to make three right turns instead of one left turn. Older drivers also have the most driving experience, which can help offset age-related changes. However, a compelling case can also be made that for certain driving situations, older adults are at differentially higher risk compared to their younger counterparts due to normative and non-normative changes in abilities (Boot, Stothart, & Charness, 2014). Three examples of these challenges are described in the next section, as well as potential solutions.

Figure 9.2 Fatal crash involvement in the U.S. as a function of driver age and year, conditionalized on the number of licensed drivers within each age group.

Source: http://www.iihs.org/iihs/sr/statusreport/article/49/1/1

While a great deal of focus has been placed on safety, it is also important to consider older adults’ driving comfort. When older adults no longer feel comfortable driving, they may cease driving altogether. Unfortunately, driving cessation is associated with many negative mental and physical health consequences. Factors that improve older drivers’ comfort on the roadway should be considered as well.

9.1.2Challenges for older drivers

Due to age-related changes in perception and cognition, older adults are overrepresented in certain types of crashes. Many of these types of crashes involve judging the speed and distance of one or more vehicles while crossing or entering a moving stream of traffic. Age-related changes in vision, spatial processing, and working memory can impair gap estimation (estimating the distance between moving vehicles), which can result in a collision. Further, age-related changes can impair the amount of information that older drivers extract from the roadway environment (e.g., signs, lane markings) that provide cues as to safe driving, and in extreme cases (i.e., cognitive impairment and dementia), can negatively influence their decision-making processes when using these cues. Although this chapter cannot comprehensively address challenges and solutions associated with aging and driving, a few examples are discussed below.

9.1.2.1Left turn maneuvers

Even though intersections account for a small proportion of the total roadway, up to 40% of crashes occur at or near intersections. Left turns in North America (right turns in countries that drive on the left side of the road) are especially hazardous for older drivers. Left turn crashes often involve a left-turning driver misjudging the speed and distance of the opposing stream of traffic they are attempting to cross. If the gap is too small, the turning driver can be struck by opposing traffic. These crashes are particularly severe because the opposing traffic is usually traveling at full speed. Greater risk is associated with age-related changes in the ability to judge safe gaps in oncoming traffic in advance of executing a turn, as well as age-related increases in fragility. Left turns can be especially challenging when the opposing left turn lane is occupied by vehicles, limiting the view of oncoming traffic.

9.1.2.2Wrong-way driving

Wrong-way crashes are among the most fatal types of crashes, though they are relatively rare. These crashes involve a driver attempting to access a highway and mistaking an exit ramp off the highway for an entrance ramp onto the highway. When a driver mistakenly enters an exit ramp, they are placed on the highway going the wrong direction. Wrong-way crashes occur when a wrong-way driver eventually crashes into a right-way driver. These crashes can involve two vehicles colliding head-on and going full speed, often resulting in multiple fatalities. Age is associated with an increased risk of being a wrong-way driver. Age-related changes in vision and perception can reduce older adults’ (especially older adults experiencing cognitive impairment) ability to perceive and recognize cues that distinguish an exit ramp from an entrance ramp (e.g., Wrong Way, Do Not Enter signs).

9.1.2.3Night driving

Driving at night presents a challenge for many older adults, and thus many avoid driving at night. However, in some cases night driving may be unavoidable. Due to a variety of changes to the eye that occur with age, far less light reaches the photoreceptors at the back of the eye of an older adult compared to a younger adult. Further, age-related changes to the eye increase the dispersion of light as it travels to the back of the eye, increasing older adults’ sensitivity to glare. Due to a variety of changes to the eye and the brain, the quality of the visual information older drivers experience at night can be far less compared to younger drivers.

9.1.3Solutions

There are several classes of solutions for reducing older adults’ crash risks and for improving their driving comfort. Referring to the framework depicted in Figure 1.3 of Chapter 1, these solutions including changing the physical environment (roadway) to support older drivers, introducing technology into the vehicle to reduce the demands on the driver’s abilities, and providing training on strategies to lessen the impact of age-related changes.

9.1.3.1Changing the roadway

9.1.3.1.1Left turn maneuvers Several strategies are recommended to reduce the left turn crash risk of older drivers. Perhaps the safest solution is to eliminate the need to judge gaps in traffic altogether by implementing a protected left turn phase in which left turning cars receive a green arrow and oncoming vehicles are stopped by a red signal. Otherwise, the left turning vehicle sees a red arrow indicating that they cannot turn. While safe, this phasing can negatively impact traffic flow by preventing left turning vehicles from taking advantage of safe gaps in traffic when available. Left turns may be especially challenging when the opposing left turn lane is occupied by vehicles, limiting the view of oncoming traffic. Here, an effective solution is to shift the opposing left turn lanes to the right to allow older drivers a less obstructed view of oncoming traffic and more time to estimate gaps (Figure 9.3). Replacing a signalized intersection with a roun...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface to the Third Edition

- Authors

- Section I: The fundamentals of aging and technology

- Section II: The fundamentals of design

- Section III: Application areas

- Section IV: Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Index