![]()

1

The Ever Changing Context of Child and Family Practice

Robyn Miller and Margarita Frederico

Introduction

Every society places the care and development of children as the highest priority. However children who come into state care, in most societies, do not do well across all areas of their development. Since the mid-2000s, work with children and families in child protection, family services and out-of-home care sectors has become increasingly complex. To improve responses to children and families in need and to achieve positive outcomes for children, many countries have engaged in significant reform legislatively, at a policy level, and within the practice culture. The reform of child and family services into a more co-ordinated and evidence-informed system is the landscape within which this chapter is situated. The aim of the chapter is to set the context for Child and Family Practice, and to highlight the importance of leadership in achieving good outcomes for children and their families. Leadership is required in all areas which impact on children and families. This includes leadership in politics, in shaping legislation in strong policies, in evidence-informed programs adequately funded, in research and in practice. As the following chapters in this book will highlight, practice leadership needs to be provided in a context where risk factors which lead to children coming into care – including poverty, conflict and racism – are addressed at all levels.

This chapter presents an overview of key themes in Child and Family Practice, utilising the Australian context as an example and drawing on international literature and comparisons. The need to have leadership supporting well-trained practitioners who think and engage systemically is an overarching theme in this chapter. It will explore the rationale for early intervention and a public health approach, and the current debate regarding evidence-based and evidence-informed practice.

A paradigm shift

Recent policy settings in the State of Victoria, Australia attempted to shift the practice culture towards a more consistent model of engagement with families, partnering with other services, intervening early in cases of abuse and neglect, and preventing harm to achieve meaningful change for the child. This is in contrast to late intervention and episodic assessment of families, monitoring of perceived risk through a procedural and task-focused approach, and programs which are fragmented and often rigid in operation. The paradigm shift, a key linking theme throughout this chapter, is towards a practice orientation to the child and the family. Good practice with vulnerable children and families requires an ecological consideration of the child’s development and culture and the impact of trauma on their safety and stability.

While identification and assessment of child abuse and neglect are the initial tasks for child protection practitioners, the ongoing and more complex challenge for systems is how to respond effectively. Frontline practitioners across child and family services engaged with vulnerable children and families are faced with complexity and, not uncommonly, volatile situations where there may be overwhelming distress.

Contemporary context

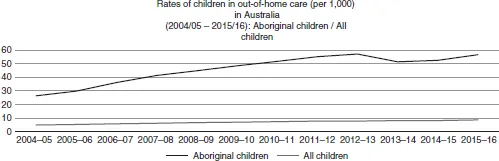

The contemporary context is one of increased public and political scrutiny (Munro, 2011). In Australia the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse has led to increased awareness of the rigor required to be a child-safe organisation. Underpinning these concepts and the reform agenda is the pervasive acknowledgement of the rights of children, families and Aboriginal communities. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), since the mid-2000s the number of children and young people in care in Australia rose from 25,454 in 2006 to 46,448 in 2016 (AIHW, 2007, p. 50; AIHW, 2017, p. 62), an increase of 82 per cent; and in 2015–16, 36 per cent of these children were from Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander backgrounds (AIHW, 2017). The situation in the USA and Canada is similar, with Native American and First Nation children over-represented in care (Trocmé, Knoke, & Blackstock, 2004; Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2016). An attempt to address this over-representation in Australia is the drive to properly resource Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCOs) to provide community-based family services. Of critical importance has been support to facilitate the transfer of Aboriginal children and young people from mainstream services to the care of Aboriginal families and communities.

Many children removed from families and communities are staying longer in care, with poorer outcomes than their peers. Reforms are geared towards preventing children and young people entering care, acting more quickly to support family reunification or permanency where indicated, reducing residential care and placing greater emphasis on keeping siblings together (Miller, 2012).

FIGURE 1.1 Number of children in out-of-home care in Australia, 2005/05–2015/16

Note: Aboriginal children = 56.6 per 1,000; all children = 8.6 per 1,000

Source: Halfpenny (2017); data sourced from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reports 2006–2017

The current approach and need for change

Concurrently, most jurisdictions experience increased societal expectations for stringent scrutiny of systemic compliance to child protection performance measures such as demands to uphold the rights of children to safety and the rights of parents to privacy. There is pressure to identify, document and manage the risk of children being harmed. Consequently, practitioners undertaking this work have insufficient time away from their computers to effectively engage with the children and families.

It is also important to recognise the ongoing tensions between child rescue and child welfare paradigms regarding Child and Family Practice. An analysis of the literature suggests that the social construction of child maltreatment and the views regarding the most appropriate interventions have been influenced by notions of blame and anxiety. British historian Henry Hendrick (1994) argued that the categories of the ‘child as a threat and the child as a victim’ functioned as dualities in the policies of the late eighteenth century. Scott and Swain (2002) noted that in Australia the child welfare movement refocused and changed around the end of World War I. Later theories were influenced by psychodynamic psychotherapists who conceptualised child abuse primarily as a disorder of the parent–child attachment, with roots in the parent’s early childhood experience. Scott and O’Neil (1996, p. 26) critiqued the dominance of this view, noting that from this perspective the problem was seen in terms of the intra-psychic ‘wounds’ from the parent’s own childhood. Of note, by the 1970s, Gil (1970) and Gelles (1973), among others, articulated a strong critique of the parental psychopathology model, and developed a structural model which privileged the prevalence and significance of social circumstances – poverty, unemployment, racism, violence and marginalisation – impacting on children and families involved with statutory services.

Despite the focus on child rescue historically, family practice was always present. Family therapy was influential from the late 1960s (Goding, 1992); and, from an infant mental health perspective, Bowlby’s work on attachment theory, and the need for infants to have a stable and secure caregiver, has been prominent since the 1950s. Bowlby was very child-focused, but absolutely clear that in order to have healthy children services must cherish their parents (Bowlby, 1951). Importantly, pioneer social workers in the past were focused on family interventions and family casework (Richmond, 1917). However, the importance of family-centred practice was frequently forgotten, and in 1988 Robin Clark (1988) critiqued the Victorian government policy settings of the day and highlighted the failure of child welfare “to conceptualize the links between services for children and those broader social policies necessary to provide social and economic conditions which enable families to bring up their children adequately” (p. 33).

Similarly, the child protection system in the United Kingdom attracted blame for being wasteful, inadequate and punitive. Spratt and Callan draw attention to the study by Cant and Downie (1994) a decade earlier, demonstrating the inherent waste of resources by systems over identifying large numbers of cases at point of referral as requiring child protection interventions, with a majority “quickly redesignated as not child protection following investigation” (Spratt & Callan, 2004, p. 202). The attempted shift from a child protection to a child welfare orientation in the United Kingdom became known as the ‘refocusing debate’ (Hearn, 1995).

In the Climbié Report, Lord Laming (2003) also noted, “[it] is not possible to separate the protection of children from the wider support to families” (p. 6). The United Kingdom Government’s response to the Climbié Report in ‘Every Child Matters’ (Department of Health and Social Care, 2003) was to both strengthen child protection and increase the number of children coming to the attention of social workers for reasons of child welfare (Hayes & Spratt, 2009).

It is notable that the United Kingdom Child Protection Review by Professor Munro clarified that previous reforms had not achieved the intended outcomes of the refocusing debate:

It may seem self-evident that children and young people are the focus of child protection services but many of the criticisms of current practice suggest otherwise. In a system that has become over bureaucratised and focused on meeting targets which reduce the capacity of social workers to spend time with children and young people and develop meaningful relationships with them, there is a risk that they will be deprived of the care and respect that they deserve.

(Munro, 2011, p. 22)

Morley (2009) notes that professional legitimacy and competence are linked to scientific, ‘objective’ knowledge and the quest for certainty. Scarce resources can be devoted to high-risk cases. Low-risk (and unsubstantiated) cases can be referred to community agencies for family support. There are, however, many critics of the surveillance rather than the welfare perspective, who state that they do not achieve the very purpose for which they have been set up: to protect children from harm (Trotter, 2006).

This phenomenon was also observed by Australia’s Victorian Child Death Review Committee (VCDRC, 2010, p. 47):

An important factor behind this lack of sufficient information being collected can be that there is not enough direct contact by Child Protection with families. Significantly, there is often even less contact with the child or children who are the subjects of the reported concerns. The committee has previously noted the relative marginalisation of children in the assessment process compared to parents when there is little direct contact with them or observation of them.

A significant aspect of this problem, in human services and also in other professions, is that human beings are reluctant to revise embedded beliefs, biases and assumptions which inform key decisions (Larrick, 2004). This directly impacts on families and children who are engaged with services. Munro (2002) noted that “[t]here is no simple antidote to this weakness. Child protection workers can be aware only of how they are likely to err and consciously try to counteract it” (p. 159). Leadership can provide additional support to workers to help them identify their biases and assumptions.

Impact of research

Inherent tensions exist between understanding the impact of harm on children, selecting the correct reports from intake for investigation, running operations of child protection and setting up systems of family services that protect vulnerable children within communities. The literature on trauma, and the evidence from neuroscience research, was ‘news’ that both stimulated and further supported change in the approach to Child and Family Practice. For example, Glaser (2000), Perry (2002), Perry (2006) and Shonkoff and Garner (2012) report on the neurophysiological processes experienced by maltreated children and young people alongside behavioural, cognitive, emotional and relational impacts. What is clear is that the impact of traumatic events at different times in the life cycle has different consequences (Atkinson, 2002; Herman, 1992). Importantly, these researchers also outline evidence that a secure attachment with a primary carer may have a buffering effect and promote healing.

However, while we know more about the impact of harm on the developing child, it is important to acknowledge what we do not know so well – how to reliably predict the most serious cases. Predicting the likelihood of harm and identifying the risk factors associated with child abuse failed to establish clear causal relationships between the variables, or reliably determine what constitutes the inter-relationships between variables posing the highest risk. Parton, Thorpe and Wattam (1997) suggested that it is more appropriate to see child abuse as a result of “multiple interacting factors, including the parents’ and children’s psychological traits, the family’s place in the larger social and economic structure, and the balance of external supports and stresses, both interpersonal and material” (p. 54).

Beginnings of a new approach

Australia, the USA and Canada, generally speaking, are reflecting a policy shift from a limited focus on risk assessment and child rescue to a more holistic understanding that the best interests of the child are served by attention to safety, stability, wellbeing and earlier intervention when a family needs help. A rights-based and developmental focus enables earlier family services intervention, greater collaboration at the local level and a more therapeutically informed care system.

However, these shifts to early intervention are not without critique. Featherstone, Morris, and White (2014) contend that early intervention involves telling parents what to do, not helping them: that it is about ‘intervention’, not practical ‘support’ (p. 1737). They believe that families are not supported or listened to, but rather have things delivered or done to them as part of a government program of ‘behaviour change’ (p. 1740).

This view is challenged by Axford and Berry (2017), who conclude that many evidence-based early intervention programs, including those designed to prevent or reduce maltreatment, are supportive and involve working alongside families. Indeed, failure to do this would render them ineffective.

The consequences of early trauma constitute a major public health problem. Children exposed to violence are more likely to suffer from traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, conduct disorders, learning problems, and substance abuse, and are more likely to engage in ...