![]()

Chapter

1

Tourism

A sociological approach

Introduction

Tourism is all things to all people. To the holiday-maker, for example, tourism may be the chance to relax and unwind, to ‘re-create’, representing a temporary period of escape from the responsibilities of work and from the stress of everyday life. Equally, it may be seen as an opportunity to do something new, to learn a new skill, to be ‘creative’ (Richards & Wilson, 2007; Richards, 2011). Conversely, for any one of the hundreds of thousands of tourism businesses around the world – from large, multinational organisations to small, independent operators – tourism is simply, by definition, business, a source of employment and income. At the same time, governments may promote or positively encourage the development of tourism, considering it to be an essential ingredient of broader social and economic development policies (Jenkins, 1991; Telfer & Sharpley, 2016). Yet, to the local residents in popular destinations, the annual influx of hordes of tourists may be seen more negatively as something to be endured or coped with (Boissevain, 1996) or, as more recently in the case of both Barcelona and Venice, to be resisted (Sharpley & Harrison, 2017).

Equally, the study of tourism may be approached from a variety of academic backgrounds or disciplines, each providing a valid basis for explanation and argument. For example, economists treat tourism as a discrete form of economic activity, relating the demand, motivation, growth, scale and form of tourism to economic factors; even the impacts of tourism, or externalities, may be explained or justified in economic terms (Dwyer and Forsyth, 2006; Mihalič, 2015; Stabler, Papatheodorou & Sinclair, 2010; Vanhove, 2011). More generally, whilst much of the early research and academic study of tourism originated as a branch of geography, a multidisciplinary approach has been increasingly adopted since the 1970s. There now exists a broad range of tourism literatures based on academic specialisms, such as anthropology (Burns, 1999; Nash, 1981; 1996; Smith, 1989a), psychology (Filep, 2012; Iso-Ahola, 1982; Pearce & Packer, 2013; Ross, 1994), law (Grant & Mason, 2003), political science (Burns & Novelli, 2007; Elliott, 1997; Hall, 1994; Matthews & Richter, 1991), history, (Shackley, 2006; Towner, 1996; Walton, 2005), cultural studies (Chambers, 1997; Meethan, 2001; Smith, 2006; 2009), marketing (Holloway, 2004; Middleton et al., 2009; Witt & Moutinho, 1989) and, of course, geography (Hall & Page, 2014; Williams & Lew, 2015). At the same time, much of the literature focuses upon particular types of tourism itself, such as heritage tourism (Boniface & Fowler, 1993; Herbert, 1995; Timothy & Boyd, 2003; Yale, 2004), rural tourism (Page & Getz, 1997; Roberts & Hall, 2001; Sharpley & Sharpley, 1997; Sharpley, 2007) and special interest (Getz, 1991; Weiler & Hall, 1992) or niche (Novelli, 2005) tourism, or on geographical or political classifications such as, for example, the UK (Yale, 1992), Europe (Davidson, 1998; Pompl & Lavery, 1993), city tourism (Ashworth & Page, 2011; Grabler et al ., 1997; Hall & Page, 2003; Heeley, 2011; Law, 2002) or developing countries (Harrison, 1992a, 2001; Reid, 2003; Telfer & Sharpley, 2016).

Despite this enormous variety of perspectives or academic approaches to tourism, however, there is one particular feature of tourism that cannot, or should not, be ignored. Unquestionably, tourism is one of the largest economic sectors in the world. Indeed, tourism is frequently described as the world’s largest industry, though it is widely debated whether or not the myriad of businesses and organisations involved in tourism should be collectively described as a single, identifiable industry. For example, it has been suggested that ‘referring to tourism as an industry may be a major contributor to the misunderstanding, resistance and even hostility that often plague proponents of travel and tourism as worthy economic forces in a modern economy’ (Davidson, 1994: 20; see also Gilbert, 1990). Irrespective of terminology, however, tourism is, according to the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTOa, 2016), ranked as the world’s third largest export category after fuels and chemicals, accounting for 7 percent of total worldwide exports and 30 percent of services exports.

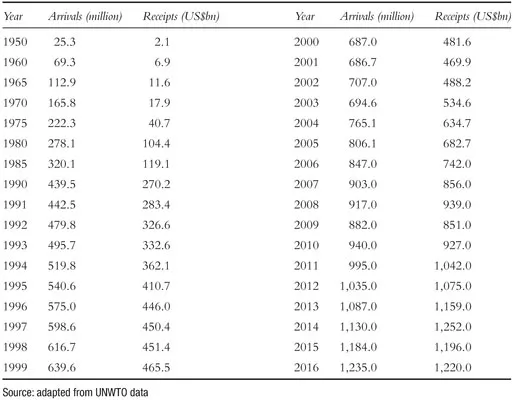

When describing tourism as an export sector, reference is being made specifically, of course, to international tourism; that is, tourism that involves travel to and a stay of at least 24 hours or more in a country in which the tourist does not normally reside or work. In other words, tourism differs from other exports inasmuch as it is consumed in the country where it is ‘produced’. As discussed towards the end of this chapter, certain types of day visitors or excursionists, such as cruise passengers, may also be categorised as international tourists, although they are not normally included in international tourism statistics. And it is those statistics that reveal the remarkable growth in the scale and value of international tourism since the mid-twentieth century. As can be seen from Table 1.1, since 1950, the year that comprehensive international tourism data were first published, international tourist arrivals have grown consistently. Indeed, arguably no other economic sector can match the long-term growth rate of international tourism.

By the end of the last century, international tourist arrivals totalled almost 690 million; just over a decade later, and despite major events such as ‘9/11’ in 2001, the SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) outbreak in 2003, the Indian Ocean Tsunami in 2004 and the global economic crisis of 2008, international arrivals have continued to increase, exceeding the one billion mark for the first time in 2012. Similarly, the value of international tourism, measured in receipts, has also grown remarkably, totalling US$1,260 million in 2015. Yet, international tourism accounts for only a relatively small proportion of all tourism activity. It is estimated that domestic tourism (that is, people participating in tourism in their own countries) is five to six times greater than international tourism in terms of numbers of trips and, according to the World Travel and

TABLE 1.1 International tourist arrivals and receipts, 1950–2016

TABLE 1.2 International tourism arrivals and receipts growth rates, 1950–2000

| Decade | Arrivals (average annual increase %) | Receipts (average annual increase %) |

|

| 1950-1960 | 10.6 | 12.6 |

| 1960-1970 | 9.1 | 10.1 |

| 1970-1980 | 5.6 | 19.4 |

| 1980-1990 | 4.8 | 9.8 |

| 1990-2000 | 4.2 | 6.5 |

Tourism Council (WTTC), if both direct and indirect expenditure is taken into account then global tourism – including domestic tourism – is a $7 trillion industry, accounting for over 10 percent of world GDP and around 9 percent of global employment.

Inevitably, the rate at which tourism has grown over the decades has declined (see Table 1.2).

More specifically, although annual growth in arrivals and receipts averaged 6.2 percent and 10 percent respectively between 1950 and 2010, between 2010 and 2015 the average annual growth rate in arrivals was ‘just’ 3.9 percent (UNWTO, 2016b), calling into question the UNWTO’s long-held prediction that, by 2020 international tourist arrivals will reach a staggering 1.6 billion, generating receipts of well over US$2 trillion (WTO, 1998a: 3). Nevertheless, there can be no doubting either that tourism, both international and domestic, will continue to grow (albeit with some transformations in the scale and direction of tourist flows reflecting, for example, the emergence of China as the dominant outbound tourism market), or that it will remain a global economic force.

Most importantly, however, the sheer scale and value of tourism should not draw attention away from the simple fact that tourism is about people. It is about millions of individuals who comprise local, regional and national societies, travelling domestically or crossing international borders and experiencing and impacting upon different societies. It is about people who are influenced and motivated by the norms and changes in their own society, who carry with them perceptions, expectations and standards based on their own personal experience and background. Above all, tourism is about people, tourists, interacting with other places and other peoples, undergoing experiences that may influence their own or the host community’s attitudes, expectations, opinions and, ultimately, lifestyles.

In short, then, the very basis of tourism is people and society. Thus, the study of tourism in general cannot, or should not, be divorced from an examination in particular of what may be termed the ‘sociology of tourism’. A fundamental issue, however, is the extent to which tourism, as an essentially social but nevertheless diverse activity, lends itself to sociological study. Specifically, the question to be asked is: is it possible to develop a sociological theory of tourism, or is it only possible to apply sociological theory to different aspects of tourism. Moreover, other academic disciplines, such as psychology and anthropology, have equal claim as a basis for research into social aspects of tourism; indeed, one of the first major texts concerned with the relationship between tourists and the local destination community (or ‘hosts’) and the social impacts of tourism is sub-titled The Anthropology of Tourism (Smith, 1977, 1989a) whilst, subsequently, both disciplines have provided the foundation for a number of books (for example, Abram et al., 1997; Burns, 1999; Franklin, 2003).

The purpose of this introductory chapter is to define the context for a sociological approach to the study of tourism. The first necessary step, then, is to examine what is meant by a sociological approach or, more precisely, the meaning, purpose and extent of sociology as an academic activity. This may then be related to, and used as a basis for the consideration of, the human and social aspects of tourism throughout the rest of this book.

What is sociology?

It is probably true to assert that although most people have some notion of what sociology is about, relatively few are able to define the term accurately. Unlike many other academic disciplines, such as history, geography and chemistry, both the scope and the purpose of sociology are either vague or, in the extreme, incomprehensible to the lay person (Browne, 1992: 1). As a result, sociology is often regarded with disinterest or, at worst, with mistrust by those who have little knowledge or understanding of the subject. Indeed, as Bilton et al. (1996: 1) point out, sociologists themselves may often feel tempted to say that they are historians or economists rather than sociologists in order to avoid the difficulty of having to explain what they really do!

This difficulty in defining sociology arises, in part, from the nature of the subject itself. For example, one explanation or description of sociology might be the study of the structure of human society and behaviour or, as Anthony Giddens explains in his widely used book, sociology may be defined as ‘the scientific study of human life, social groups, whole societies and the human world as such (Giddens, 2009:6). Although essentially accurate, this perhaps over-simplifies what sociology is. That is, it is certainly concerned with specific aspects of society, such as the family, class and gender divisions, work, religion or deviance (behaviour which does not conform to what is considered to be ‘normal’, crime being the most obvious example). Indeed, many introductory sociology texts are structured according to these social institutions (for example, see Abercrombie et al., 2000; Browne, 2011; Giddens, 2009). This is, however, only half of the story. Of equal, if not greater, importance is the approach or perspective which determines how these particular aspects of society and the behaviour of individuals within society are studied. Sociology is, in effect, a way of looking at society. As Browne (1992:2) suggests, ‘sociologists use a sociological imagination . . . they study the familiar routines of daily life . . . in unfamiliar ways’ or, as Giddens (2009: 6) puts it, ‘the sociological imagination requires us, above all, to “think ourselves away” from the familiar routines of our daily lives in order to look at them anew’.

In other words, the basis of sociology is society. Society is made up of individuals who, with the exception of those who make a conscious decision to avoid contact with other people, perform or participate in a huge variety of actions every day. The great majority of these actions are socially acceptable or normative (that is ‘normal’, expected behaviour); they are also, however, socially determined. That is, an individual’s behaviour is generally constrained, or determined, by their society’s rules, rules which may be set down by custom, by religion, or by laws. As a result, all the individual actions within a given society tend to occur in a co-ordinated fashion so that social life remains reasonably ordered and predictable. For example, in many Western societies it has long been considered ‘normal’ for a young person to take a year off in between school and university to go travelling – to take a so-called ‘gap-year’ (O’Reilly, 2006). Conversely, an individual who does so in, say, his or her forties, might once have been considered unusual, eccentric or even, perhaps, irresponsible. However, as societies develop, social rules or norms also develop and change. In the UK, for example, almost half of all ‘gap-year’ tourists are now in fact older, middle-aged people taking a career break or even travelling in early retirement. At the same time, it has become more socially acceptable, or perhaps even expected, to do something ‘useful’ while on gap-year travels, hence the contemporary popularity of so-called volunteer tourism (Callanan & Thomas, 2005; Wearing & McGehee, 2013), a form of tourism that is discussed in more detail in Chapter 4.

The important point, therefore, is that sociology is concerned not only with the structure of society and the behaviour of its members but also with the rules, or wider social forces, that determine social structure and those patterns of behaviour. It is this latter characteristic that differentiates sociology from other disciplines, such as anthropology, and that causes most confusion amongst non-sociologists.

Whereas many people attempt to explain or describe different forms of human behaviour as natural, instinctive or just plain common sense, all of which place the emphasis firmly on the ability of the individual to make his or her own decisions, sociology to some extent rejects notions of individuality and places human behaviour within the wider context of social forces which are beyond the control of the individual. Also, socially normal or acceptable behaviour is, of course, relative to different societies and reflects a particular society’s rules or constraints that must be learned by the individual. Thus, ‘one person’s “common sense” is somebody else’s nonsense’ (Bilton et al., 1996:6). For example, in Western societies it is generally accepted as common sense or normal that it should be men, rather than women, who undertake heavy labouring work; in some other countries, such as India, it is more often that such work is done by women, a role determined by the social forces of religion, male dominance and the caste system (Baker, 1990) whilst increasing numbers of women are working on building sites following the recent construction boom in Cambodia (Fox, 2017).

The basic tenet of sociology, then, is that human society and behaviour is structured, moulded and constrained by wider social forces and influences, and it is this approach that underlies sociological research and analysis. Yet, although sociologists share this common approach, there is a variety of theories about what society actually is, how it may be explained and, hence, how it determines individual behaviour. The following section briefly traces the development of sociolog...