eBook - ePub

Pediatric Neurology

- 362 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pediatric Neurology

About this book

The fundamental goal of the revised edition of this acclaimed text is to provide comprehensive, practical, and straightforward information about the developing nervous system that is as relevant to those embarking on careers in pediatric neurology as it will be to the experienced practitioner who cares for infants, children, and adolescents. New to this edition are chapters on tumors of the nervous system, autism and related conditions, and practice parameters in child neurology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pediatric Neurology by James Bale,Joshua Bonkowsky,Francis Filloux,Gary Hedlund,Paul Larsen,Denise Morita in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Family Medicine & General Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION 1

CORE CONCEPTS

CHAPTER 1

The neurological

examination

Main Points

- The clinician uses the history and diagnostic studies to answer ‘What is the lesion?’ and the neurological examination to answer ‘Where is the lesion?’

- The clinician hears and sees the effects of disease and uses powers of reasoning to identify the biologic cause.

- The temporal profile or chronology of disease enables clinicians to hypothesize the nature of the lesion.

- The elements of the adult neurological examination are the foundation for the pediatric examination and the verbal child can be taught the examination.

- The pediatric neurological examination must be conducted and interpreted in the context of expected neurodevelopmental milestones.

- For the preverbal child, the examination must be tailored to the age-specific expectations of the developing nervous system.

- Many neurological deficits can be detected by watching the child walk, talk and play.

Introduction

A clinician hears and sees the effects of disease in patients and uses this information and deductive powers to identify the cause of the signs and symptoms. This ‘Sherlock Holmesian’ process is common to many areas of medicine, and neurology is no exception. Essential in this diagnostic process is the clinician’s ability to answer two basic questions: ‘Where in the nervous system is the lesion?’ and ‘What is the lesion?’ The first question can be answered by combining historic information and the neurological examination. The second question, ‘What is the lesion’, is often suggested by the patient’s history or examination and confirmed by the appropriate laboratory or neurodiagnostic tests. Consequently, this chapter addresses first the key elements of the neurological history and then focuses on the neurological examination.

What is the lesion?

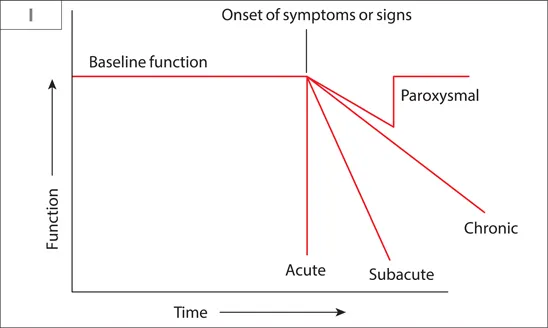

The pediatric patient presents with a chief complaint and a history of the present illness. This complaint and present illness must be viewed in the context of the past medical history, family history and social history. With this information, the clinician constructs a temporal profile of the child’s illness. This temporal profile can be conceptualized as a graph with Function on the vertical axis and Time on the horizontal axis (Figure 1). The patient’s baseline function on the vertical axis is determined by his past history, family history and social history. The chief complaint and the present illness represent a departure from this baseline level of function. The chronology or the period of time over which the present illness evolves is critical in determining the most likely disease process that has caused the symptoms.

The common pathologies of the nervous system have relatively stereotyped patterns in which they appear. The time line can be acute (seconds, minutes, hours), subacute (hours, days), chronic (days, months), or paroxysmal (episodes of illness with returns to baseline). These semantic qualifiers – acute, subacute, chronic and paroxysmal – are key elements in clinical reasoning and the formulation of hypotheses regarding the cause of a neurological deficit. An adolescent, for example, can present with a left hemiparesis. If the hemiparesis developed over a matter of seconds, it is most likely the result of a stroke. If it developed over a period of several months, stroke is now unlikely and a brain tumor must be considered. Not only do these pathologies have typical temporal profiles, they can be considered in terms of whether they produce focal or diffuse brain dysfunction and whether the disease process is static or progressive. The typical temporal profile, localization and course of the most common pathologies that affect the brain are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1 The temporal profile of neurological disease, depicting acute, subacute, chronic or paroxysmal changes from baseline.

Two additional aspects of the history deserve special emphasis in pediatric neurology, the developmental history and the family history. The child’s nervous system is a dynamic and maturing organ system. Whether the child reaches appropriate developmental milestones and the rate at which the child achieves these milestones are important indicators of brain function. The clinician must obtain a concise history regarding when developmental milestones were achieved. As many conditions of the child’s nervous system have a genetic basis, a complete family history must be obtained. A useful question to ask is: ‘Does anyone else in the family have anything similar to your child’s problem?’ Creating a family pedigree helps the family and the clinician construct a thorough family history.

Table 1 Temporal profile and localization of important pathologies affecting the brain

Acute

Vascular/infarct – focal

Hypoxic – diffuse

Trauma – focal or diffuse

Subacute

Inflammatory/infectious – focal or diffuse

Immune – focal or multifocal

Toxic/metabolic – diffuse

Chronic

Congenital – focal or diffuse

Degenerative – diffuse or system related

Neoplastic – focal

Paroxysmal

Seizure – focal or diffuse

Vascular/syncope – diffuse

Pain/headache – focal or diffuse

Where is the lesion?

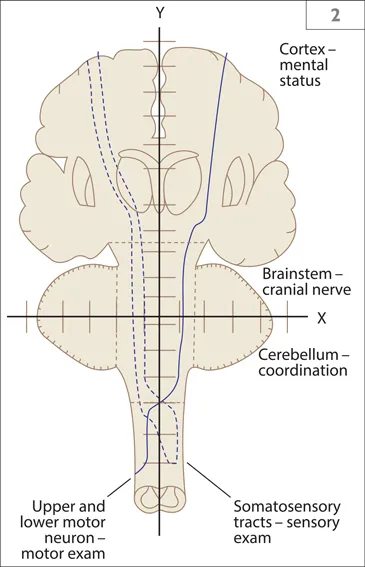

The history provides important etiologic clues, but the neurological examination and neuroimaging studies confirm the anatomical location of the child’s chief complaint. The neurological examination is the window through which the clinician views the nervous system. When the examination is approached in a systematic and logical fashion organized by anatomical levels and systems, the clinician can use findings to determine the location of the lesion causing the child’s symptoms. To facilitate anatomical localization, the clinician can think of a coronal view of the brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves superimposed on an ‘x,y’ graph (Figure 2) with the level of brain function on the vertical axis and the right, left and midline location on the horizontal axis. Ascending and descending systems exist at multiple levels and cross the midline during their course, enabling localization on both vertical and horizontal axes.

Elements of the neurological examination allow the physician to obtain x and y values so that an anatomical location can be determined. On the vertical axis are the cerebral cortex, brainstem, cerebellum, spinal cord, muscle and peripheral nerves; each structure has a left and right side. The corresponding elements of the neurological examination for each of these levels are: cortex – mental status exam; brainstem – cranial nerves (CNs); cerebellum – coordination; spinal cord, muscle and peripheral nerves – sensory and motor. The motor system involves all levels, including peripheral nerve and muscle. The sensory and motor systems are not only located in the spinal cord and peripheral nerve, but also ascend or descend through the brainstem and the cerebral hemispheres. Because they decussate at the level of the spinal cord or lower brainstem, findings on motor and sensory examinations have considerable localizing value when combined with CN, cerebellar or cortical findings.

Figure 2 The neuraxis of neurological localization.

A few examples help illustrate the power of this approach to anatomical localization. A child presents with a right hemiparesis and left hemifacial weakness. The only place that the lesion can be located in the neuraxis is at the level of the pons on the left side where the 7th CN nucleus and corticospinal tract are located. When the disorder begins insidiously, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may confirm the presence of a brainstem glioma. If the child has acute aphasia and a right hemiparesis, the lesion must be at the level of the cerebral hemispheres on the left side where the corticospinal tract or motor cortex is located near the speech centers of the brain. MRI, using diffusion-weighted images, may demonstrate acute ischemia affecting the distribution of the right middle cerebral artery. Similarly, if the child has weakness of the legs, loss of sensation below the nipple line and preserved arm function, the lesion must be at or near the T4 level of the spinal cord. MRI may show demyelination or inflammation compatible with multiple sclerosis, transverse myelitis or acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder.

This approach to anatomical localization is necessary for evaluating children, but it is not sufficient. The interpretation of the neurological examination must be couched in the context of neurodevelopmental milestones. What one expects from a newborn is vastly different from what one expects from a child or adolescent. Expression of motor and cognitive function is influenced immensely by the maturation of the nervous system. Patterns of development are important indicators of childhood brain dysfunction and must be considered when establishing anatomical localization.

In many instances the neurological examination will be norm...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface to the second edition

- Abbreviations

- SECTION 1: CORE CONCEPTS

- SECTION 2: PROBLEM-BASED APPROACH TO NEUROLOGICAL DISORDERS

- Further reading

- Index