eBook - ePub

The Sixties

Terry H. Anderson

This is a test

Share book

- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Sixties

Terry H. Anderson

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Sixties is a stimulating account of a turbulent age in America. Terry Anderson examines why the nation experienced a full decade of tumult and change, and he explores why most Americans felt social, political and cultural changes were not only necessary but mandatory in the 1960s. The book examines the dramatic era chronologically and thematically and demonstrates that what made the era so unique were the various social "movements" that eventually merged with the counterculture to form a "sixties culture, " the legacies of which are still felt today. The new edition has added more material on women and the GLBTQ community, as well as on Hispanic or Latino/a community, the fastest-growing minority in the United States.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Sixties an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Sixties by Terry H. Anderson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1 The Years of Hope and Idealism, 1960–1963

On the afternoon of February 1, 1960, four African American students at North Carolina A&T College walked into the local Woolworth’s in Greensboro, North Carolina. Two of them bought toiletries, and then they all walked over and sat down at the lunch counter. A sign on the counter declared the Jim Crow tradition throughout the South: “Whites Only.”

A waitress approached, and Ezell Blair Jr. ordered. “I’d like a cup of coffee, please.” The waitress answered, “I’m sorry. We don’t serve Negroes here.” Blair responded, “I beg to disagree with you. You just finished serving me at a counter only two feet away from here. . . . This is a public place, isn’t it? If it isn’t, then why don’t you sell membership cards? If you do that, then I’ll understand that this is a private concern.” “Well,” the waitress responded heatedly, “you won’t get any service here!” She refused to serve the black students for the remainder of the afternoon. When the store closed at 5:30 p.m., the students left, and one of them said to the waitress, “I’ll be back tomorrow with A&T College.”

They became known as the Greensboro 4, and that evening on their campus they spread the word of the sit-in. The next morning about 30 male and female black students walked into Woolworth’s and sat at the lunch counter. Occasionally a student would try to order but was not served. After two hours they ended the sit-in with a prayer. The next day about 50 sat at the counter. This time they were joined by three white students, and by the end of the week hundreds of black students from a half dozen nearby campuses appeared.

The sit-in movement spread rapidly across the South. Always dressed nicely, acting politely, some students read Henry David Thoreau’s classic essay “Civil Disobedience” while others read the Bible. In the weeks after Greensboro, black students started sit-ins at lunch counters in Winston-Salem, Durham, Raleigh, and other cities across North Carolina, and during the spring activists were using the tactic in most southern states, from Nashville to Miami, from Baltimore to San Antonio. Blacks also began read-ins at libraries, paint-ins at art galleries, wade-ins at beaches, and kneel-ins at white churches. In Philadelphia, 400 ministers asked their congregations not to shop at businesses that did not hire blacks. Throughout 1960 and the next year, about 70,000 participated in various protests in 13 states, and a newspaper in Raleigh noted that the “picket line now extends from the dime store to the United States Supreme Court and beyond that to national and world opinion.”

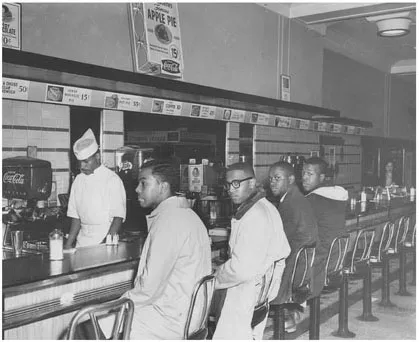

Figure 1.1 The second day of the Greensboro sit-in; from left, Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Billy Smith, and Clarence Henderson. (Credit: Greensboro News and Record)

The sit-ins were the first phase of the national Civil Rights Movement, and the reasons for that activism had been clear for some years. In the land of the free, some citizens were more free than others, although all were guaranteed the same liberties by the U.S. Constitution. Although blacks made some progress boycotting buses in Montgomery and a few other cities, victories were only local triumphs. Much more typical was that southern states and cities simply ignored federal court rulings, and to appease conservative voters, presidents enforced those decisions only when confronted—such as at Little Rock. Although the U.S. Constitution guaranteed the right to vote for all citizens, the vast majority of southern blacks could not vote in 1960 because local white officials would not allow them to register. Although the Supreme Court mandated integration at public parks, beaches, golf courses, and in interstate travel, those facilities and transportation remained segregated. And although the Court ordered integration in the Brown case in 1954, not even 1 percent of southern schools integrated per year. At that rate, Martin Luther King Jr. noted, his children would be sitting in school next to white kids in the year 2054.

Law versus Tradition: The sixties became the era when those two clashed, a main reason why the decade became one of “Tumult and Change.” In 1960 law was the underdog, so if blacks wanted civil rights they would have to use other tactics to change the segregated South. Martin Luther King Jr. called for nonviolent direct action, and Franklin McCain did that in Greensboro, asking “At what point does a moral man act against injustice?” “It was the best feeling of my life,” McCain later said, “sitting on that dumb stool.” Sit-ins were the first example of that tactic in the sixties, and they not only integrated lunch counters, but also stimulated many more students to become activists. They formed an organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and they began calling their activism a new name: “the movement.”

Yet being part of the movement could be dangerous. In Greensboro, white youths appeared at Woolworth’s, threatened blacks, and eventually someone telephoned that if the sit-in did not stop a bomb would be detonated. The manager closed the store, and the mayor called for talks. That was a typical white response: officials formed committees to “study” proposals to end segregated seating while at the same time they applied pressure on older black leaders to control their youth and demanded that black college presidents expel activists. During the first year of the sit-ins, black college administrators expelled over 140 students and fired almost 60 faculty members. Nevertheless, the sit-ins spread, and so local police arrested peaceful activists for “inciting a riot,” jailing about 3,600 in the year after the Greensboro 4. Short jail time did not stop the sit-ins, and so some white southerners began the unofficial response—violence. In Atlanta, a white threw acid into a demonstrator’s face, and during sit-ins in Houston, a white teenager slashed a black with a knife. Three others captured a protester, flogged him, carved “KKK” in his chest, and hung him by his knees from a tree. When blacks tried to integrate public beaches in Biloxi, Mississippi, white men chased them with clubs and guns, eventually shooting eight; local police arrested blacks for “disturbing the peace.”

Repression in the past usually had worked, but not in 1960. Just the opposite; it created a common bond for black students, gave them a new sense of pride, and encouraged many of them to try harder to beat segregation. These were “ordinary” folks, often local people, doing the extraordinary—putting their lives on the line—and this time there was no turning back.

Why? Why would a student or a sharecropper get involved and become an activist? Some had been inspired by parents, older civil rights workers, teachers, or by Martin Luther King Jr. Ezell Blair had heard King preach two years before he joined the Greensboro sit-in, and recalled the sermon being “so strong that I could feel my heart palpitating. It brought tears to my eyes.” Others were inspired by decolonization in Africa, where at that time a dozen nations were obtaining independence, and activists were wondering when they would get equality in the land of the free; the sit-ins, one wrote, were a “mass vomit against the hypocrisy of segregation.” Many more were simply fed up with being humiliated. As black students in Atlanta proclaimed, “Every normal human being wants to walk the earth with dignity and abhors any and all proscriptions placed upon him because of race or color.”

Significantly, these issues now were being televised at prime time. It is difficult to overestimate the importance of TV in the sixties. Numerous authors have debated the impact of the media on the Vietnam War and antiwar movement, and one wonders if bus boycotts during the fifties would have remained local incidents if more white and black homes had televisions or if network coverage had been more extensive.

By 1960, however, Americans had purchased 50 million TVs, and during the next years the network evening news expanded from 15 minutes to a half hour, provoking interest in national issues. The sixties became the first televised decade, and the first show was civil rights. At predominantly black Howard University, Cleveland Sellers recalled students staring at the TV news, so quiet “you could hear a rat pissing on cotton. . . . My identification with the demonstrating students was so thorough that I would flinch every time one of the whites taunted them. On nights when I saw pictures of students being beaten and dragged through the streets by their hair, I would leave the lounge in a rage.” With more extensive TV coverage, virtually every citizen could witness—and judge—Jim Crow segregation.

Another reason for becoming an activist was that this generation of students had been raised in Cold War America. The fifties were an unusually patriotic era in which teachers had baby boomers begin the school day with the Pledge of Allegiance, “with liberty and justice for all,” and then students memorized the words of the Constitution, “We the people,” and the Declaration of Independence, “All men are created equal.” Yet when these students turned on the TV or read newspapers, they quickly realized that such words rang hollow. “The whole country was trapped in a lie,” said activist Casey Hayden. “We were told about equality but we discovered it didn’t exist.”

The movement aroused hope and idealism during 1960, and so did the campaign of John F. Kennedy, another demonstration that the nation had entered a new era—the sixties.

The Torch Has Been Passed

Senator John Kennedy inspired many during his bid for the Democratic nomination. Previously, Kennedy had not displayed much support for civil rights, but the sit-ins forced the candidate to consider the issue. In June 1960 the senator met King, and he later told a group of African diplomats that “it is in the American tradition to stand up for one’s rights—even if the new way to stand up . . . is to sit down.” Just two weeks before the November election, King and 50 other activists were arrested during a sit-in at a department store in Atlanta. The others were released, but King was held in jail. The Republican candidate, Vice President Richard M. Nixon, had no comment, but JFK called Coretta Scott King, who was pregnant, and expressed his concern. Shortly thereafter, King was released and praised Kennedy; King’s father, who had favored Nixon, now declared his support for JFK. Although the episode was neglected by the white press, it was publicized in African American papers and celebrated at their churches, resulting in a large turnout of the black electorate in key northern cities.

Yet civil rights was not the central issue of the 1960 election; the main concerns were the Cold War and the economy. A year earlier, guerrilla leader Fidel Castro had ousted the U.S.-supported dictator in Cuba, and then Castro alarmed his neighbor to the north by announcing he was a Communist and by expropriating American businesses on the island. Communism emerged just 90 miles from Florida. In response, President Eisenhower protested throughout 1960 and eventually broke diplomatic relations. Relations with the Soviet Union were not much better. In May, the Soviet Union shot down an American U-2 spy plane above their country. Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev demanded an American apology for violating Russian airspace. When President Eisenhower refused, tempers flared at the Paris summit meeting and the Soviet leader marched out of the conference, denouncing “American aggression.” At home during the 1960 campaign, the economy had lapsed into a short recession resulting in industrial stagnation and rising unemployment.

During the first months of the campaign, Kennedy had one “character” problem: he was a Catholic, and none had ever been elected to the presidency. He confronted the issue directly. “I am not the Catholic candidate for President,” he said. “I am the Democratic Party’s candidate . . . who happens to be Catholic.” He told Protestant ministers, “I believe in an America where the separation of Church and State is absolute,” where no church or parochial school should be granted “public funds or political preference.” That seemed to dismiss the doubts of most voters.

The campaign heated up, and the vice president focused on his years of apprenticeship under Eisenhower, who remained popular. Nixon talked about experience and leadership, presented himself as the successor to Ike, and promised continuity, not change. Kennedy spoke of change: “The old era is ending. The old ways will not do.” But Kennedy’s idea of change was not to move away from previous policies. Indeed, he would be tougher on Communism. He declared a “missile gap” supposedly in favor of the Soviets, and he claimed that he would be better for the economy, promising to “get the nation moving again,” pledging a 5 percent growth rate. He asked the nation to reach out:

We stand today on the edge of a New Frontier—the frontier of the 1960s—a frontier of unknown opportunities and perils—a frontier of unfulfilled hopes and threats. . . . The New Frontier of which I speak is not a set of promises—it is a set of challenges.

The polls showed a very close race as the candidates held the first televised presidential debates. Interest soared, and 70 million Americans watched the first encounter. Nixon appeared tired from the campaign, dark and haggard, struggling to make a good impression. Kennedy was the opposite—fresh and vibrant, handsome and relaxed, eager to address the nation, optimistic about the future. The candidates differed little on the issues, but that was not the point: the message was image, and the Kennedy image won on TV. “That night,” stated one commentator, “television replaced newspapers as the most important communications medium in American politics.”

The election was one of the closest in history. Over 68 million votes were cast and Kennedy won by only 112,000. Voters who saw the debates favored Kennedy, and the Democrat’s vice presidential pick, Texas senator Lyndon B. Johnson, proved invaluable in his home state and throughout the South. In the North, the Catholic blue-collar and the urban black votes were decisive. African Americans delivered Illinois and Michigan—and the election—to Kennedy.

“Let us begin anew,” the youngest president ever elected said in his inaugural speech. “Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans.” The new chief executive quickly set the mood of the nation—hope and idealism. He confronted the complacent fifties by challenging citizens to get involved, to make a commitment: “And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” He appointed advisers from Ivy League colleges whom the press dubbed “the best and the brightest,” and they talked about “new frontiers” and a social agenda that would spread affluence and middle-class status to all. With his flash and dash the new president ushered in an era of rising expectations— he stirred America out of its fifties slumber.

Camelot, it was later called—the handsome 43-year-old president, his beautiful young wife, 32, and the best and brightest advisers. They moved into Washington in January 1961, and the media buzzed with terms such as glamour, vision, progress, vigor. Times were changing. The youthful president and his friends played touch football on the White House lawn, and as they ran out for passes his administration initiated a physical fitness program; soon youngsters were exercising in schools and soldiers were trying to outdo each other on 50-mile hikes. At the White House, a parade of famous actors, artists, and musicians entertained the president and first lady. Washington seemed to glitter, or as adviser Arthur Schlesinger Jr. observed, “to make itself brighter, gayer, more intellectual. . . . It was a golden interlude.”

JFK appealed to liberals, naturally, and to intellectuals and youth. “Kennedy created a climate of high idealism,” recalled a professor, “it was evangelical.” The president also excited a large crop of teenagers as they began thinking about their future. He aroused them by asking if they would give their time and energy in a “peace corps” aimed at helping people in emerging nations. He inspired them to think about a hopeful, bright future. “The whole idea,” stated a teen, “was that you can make a difference. I was sixteen years old and I believed it. I really believed that I was going to be able to change the world.”

That was the Kennedy promise—you could make a difference—and such ideas stimulated optimism. He asked Congress to pass his legislative program, the New Frontier, which included a raise in the minimum wage and surplus food distribution to alleviate poverty, an education bill to reduce overcrowding in public schools, a tariff reduction to increase trade, a cut in taxes to stimulate the economy, and a health care program for the elderly.

Less than two months after his inauguration, JFK established the Alliance for Progress, an attempt to combat Castro’s revolutionary appeal in Latin America and to help those nations have a future “bright with hope” by directing U.S. foreign aid not only toward economic development but also for social justice. More importantly, JFK initiated the Peace Corps, calling on young Americans to help in the “great common task of bringing to man that decent way of life which is the foundation of freedom and a condition of peace.” The Washington Post called it an “exciting idea,” the New York Times labeled it “a noble enterprise,” and the response was immediate and overwhelming, demonstrating a new decade of idealistic students. Within an hour after the announcement of the corps, the government switchboard could not handle all the calls from potential volunteers: “some 6,000 letters of suggestion, inquiry, and open application. None mentions salary.”

College students seemed to come alive that spring, partly because of JFK and also because of civil rights sit-ins and atomic fear; for the ...