![]()

PART I

ARCHITECTURE AND THE

RETURN TO THE INNER CITY

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The New Tenement

JUDGED BY THE GOALS of the 1970s, today’s city centres are a great success. All over Europe and beyond inner cities are no longer neglected and declining, but have turned into attractive places of residence, where high standards of living are matched by pleasant buildings, appealing parks and squares, and a palpable experience of local history.

They thus seem to neatly fulfil the needs of their most conspicuous group of inhabitants: well-educated professionals who work hard and play hard, rely on face-to-face communication to perform in their increasingly flexible jobs, think global and act local, cherish both multicultural life and place-specific character, and often live in non-traditional family relations. They also seem to be the share of the population who are least threatened by rising real-estate prices, increasing social inequality, and dwindling public services.

And yet the changes in the urban environment over the last 50 years did not originally aim at the comfort of a new middle class. They were started by welfare state institutions rather than neo-liberal policies. They were first supported by working-class activists and local nonconformists. They were meant to strengthen local culture and identity against the destructive aspects of modernisation. And they were intended to reinforce urbanity as a liberating and creative form of human existence.

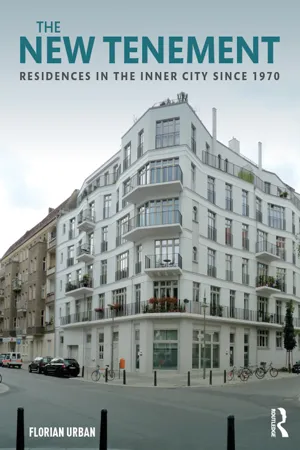

The metamorphosis of many inner-city neighbourhoods from depopulating “slum areas” with crumbling ports and factories to icons of local pride and domicile for the winners of the post-industrial economy is closely tied to its most noteworthy architectural manifestations. Late twentieth and early twenty-first century urban residences were decidedly different from the modernist towers and slabs of the postwar period. They often look like updated versions of what in Berlin traditionally would be called Mietskasernen (rental barracks), in Vienna Zinshäuser (rental houses), in Warsaw kamienicy (stone houses), and in Glasgow, New York or Montreal tenements.

This book is about these new tenements, focusing predominantly on Berlin, Copenhagen, Glasgow, Rotterdam and Vienna. It is about “tenements proper,” four-to-seven storey walkups on the block perimeter with ornamented façades and often with shops and offices on the ground floor—buildings that are typologically similar to historic tenements Berlin or Copenhagen or to turn-of-the-twentieth-century mansion blocks in London or Paris. It is also about other dense urban residences that were built since the 1970s to enliven the city centres: medium-rise blocks built with a setback from the street, three-storey terraced townhouses, or three-to-four-storey “urban villas.” Most have appealing façades and connect to carefully designed public spaces. Most form regular blocks or “fruit salad estates,” which in one development comprise building of diverse outlines and heights. And most are design variations within a regulatory framework along the principles that Aldo Rossi, Herman Hertzberger and other late-twentieth-century proponents of typological continuity famously called for.1 They frequently include commercial spaces to provide the kind of functional mixture advocated by post-functionalist urban theorists from Jane Jacobs to the New Urbanists.2 They provide “structural openness” which, like many pre-modern and unlike most functionalist buildings, makes them easily adaptable to different uses.3 And they were largely built as middle-class dwellings for both tenancy and owner occupation.

This book is also about the post-functionalist city that generated these new buildings, which is very different from the industrial metropolis with its traditional tenements or the functionalist city with its towers in a park. It is a city of information exchange rather than industrial production, of individual expression rather than mass culture, and of conspicuous difference rather than egalitarianism. It is nonetheless a city where, particularly in Europe, heterogeneity and economic disparities are still to a certain extent balanced and controlled by public institutions. It is a city where the privileged tend to live in the centre rather than on the periphery and cherish urban spaces for both work and leisure. And it is a city that positions itself against other cities and proudly communicates its specificities to a domestic and international audience.

New tenements evolved along with municipal policies to strengthen the centre. They also started being built during the demographic tipping point in the 1980s, when after decades of shrinkage many European city centres started growing again.4 The actual growth figures might appear marginal in comparison to the explosion of urban populations in the Global South, but were significant in the European context where the respective countries as a whole barely grew. While population increase did not spark the regeneration policies—all over Europe they were initiated before cities started to grow again—it produced a pressure to build more and denser and thus accounted for the progressive spread of new tenement typologies.

This “return to the inner city” was noticeable not only in Europe but also in North America, and to a certain extent also in other regions of the world. New tenements are thus frequent in many cities, including Paris, London, New York, San Francisco, Montreal, Amsterdam, Barcelona, and others. At a global level, they are related to a discourse on dense urban environments that also generated New Urbanism in the USA and elsewhere, and some of the new towns in China or the Middle East.

New tenements nonetheless rely on conditions that are particularly prominent in Europe and therefore only to a certain extent comparable to the dense multi-storey buildings in Seaside in Florida, Anting near Shanghai or Masdar City in Abu Dhabi: a highly regulated environment unfavourable to insular developments and gated communities, a comparatively low degree of car dependency, and a comparatively small gap between rich and poor. This European socio-political framework was crucial in the development of new tenements and determined their further mode of operation.

This book is also about a new discourse on the positive qualities of urban life. This new intellectual framework mixed anti-modernist criticism with nostalgic images and strategic goals, absorbing ideas about the city as a generator of creativity and innovation, locale of democracy and productive debate, and object of identification and personal attachment. New tenements were connected to this discourse, on the one hand, through their characteristics. They generated public space in the form of traditional squares and corridor streets and were therefore perceived as a counterproposal to the bleakness and disorienting arrangement of many modernist tower block estates. On the other hand they were also related to a revised view of the nineteenth-century metropolis, which since the 1970s was no longer predominantly connected to blight, filth, and oppression, but rather to intellectual advancement, political reform, and artistic innovation.5

This positive reframing of city life did not reverse the on-going attractiveness of suburban housing. But it inspired policies of urban regeneration and promoted the value of inner-city dwelling. In this way new tenements were the built outcomes of a cultural shift informed by collective imagination (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 Poster announcing construction of dense residences on the site of recently demolished tower blocks, Gorbals and Norfolk Streets, Glasgow, 2016

NEW TENEMENTS AND THE POST-FUNCTIONALIST CITY

NEW TENEMENT design was influenced by the different ideas about city planning in the twentieth century. These include modern technological standards and a long-standing concern with parks and greenery, as well as post-functionalist planning principles such as density, functional mixture, social diversity, and respect for the historical context. The architectural vocabulary is similarly diverse, ranging from functionalist austerity to postmodern plays with meaning, precedent, and pop-cultural references.6

New tenements are also connected to the socioeconomic changes in the late twentieth century that political economists have referred to as the “condition of postmodernity.”7 These include the end of Fordist mass production and mass consumption (the beginning of the “post-Fordist regime”), the receding of the welfare state, the rise of neo-liberalism, and a new stage of globalisation as a result of intensified trade and migration.8 These changes significantly affected large cities: public spaces were privatised, historic buildings were increasingly commodified and marketed to tourists, inner cities were restructured for leisure purposes and image marketing gained significance. At a more general level these changes were also connected with postmodernism in art, architecture, and philosophy.9

This book uses the study of new tenement architecture as a way of exploring this condition of postmodernity in the urban environment. Architecture mediates power and is part of what Michel Foucault described with his concept of governmentality—a principal element in the regulatory system that determines behaviour and structures human life.10 As factors in the mesh of governmentality new tenements are both actors and results of changed power relations. These buildings were designed by creative architects who promoted their vision of a traditional big city compatible with the requirements of late-twentieth-century life. At the same time the dwellings also adjusted their inhabitants to the intricacies of post-functionalist living, whose characteristics included home offices, patchwork families, and decreasing car ownership. The new buildings thus were also effective promoters of social change, just in the same way as modernist blocks had once introduced mid-twentieth-century urbanites to nuclear family life, increased privacy, and electric appliances.

New tenements were also both actors and outcome of an intellectual framework that shaped—and in a way produced—the subjects of existing power relations.11 As such they were connected to various other actors: entrepreneurs and workforce of economic production, politicians and administrators who set legal frameworks for planning and construction, the users whose preferences constituted changing housing markets as well as the architects and designers who created new forms of cultural expression.

METHOD AND LITERATURE

THIS BOOK AIMS to explain why today’s inner-city neighbourhoods look the way they do. It compares and analyses five cases that evidence a development that is noticeable all over Europe and beyond. While most cities could have served as examples, Berlin, Copenhagen, Glasgow, Rotterdam, and Vienna were chosen, among others, because they exemplify the new tenement themes in a particularly salient way. They not only feature prime examples of new architecture, but also la...