![]()

Part I

The Foundations

![]()

Chapter 1

History of Instrumental Music

Knowledge of the history of instrumental ensembles is not essential for success as a band or orchestra conductor; still, it seems appropriate to begin a book on instruments and instrumental teaching with a brief historical survey. In addition to the intrinsic interest which history holds for us, there is a practical value in the perspective gained from knowledge of history. One can become aware of trends, observe the ways in which things were done at previous times, make contact with objectives, procedures, and methods, and gain a greater understanding of the reasons behind present practices and present situations. The extramusical outcomes become evident; e.g., community and industry bands and orchestras contributed to the cohesion felt by immigrants as they contributed to the kind of country they believed America could become. One hopes that such knowledge will help the teacher plan upon sound bases, avoid mistakes of the past, and shape the future intelligently.

The Development of Instruments

The earliest common use of instruments, recognizable ancestors of our modern woodwinds, strings, drums, and brasses dates to several thousand years BCE. The flute, drums, and perhaps reed instruments were apparently a part of human history for some thirty thousand years. Ensembles of flutes, lyres, reed, and brass instruments were part of early Greek and Asian celebrations and in support of military exercises. Little development of group instrumental music as we know it occurred until the modern orchestra had its beginnings with the creation of opera at the close of the sixteenth century. The orchestras grew in size and importance as opera became a favorite form of entertainment. As early as Monteverdi, instruments, as crude as they were, were used to portray mood and character, perhaps the first such use of instruments for their unique, individual qualities. Thus, a need was established to improve and create more flexible instruments.

The Development of the Orchestra

Because the violin is the heart of the orchestra, the modern orchestra was not possible until the seventeenth century, when the great Italian violin makers perfected their craft and created the master instruments. The first good orchestra is considered to be the “Twenty-four violins of the King,” in the service of Louis XIII of France, which reached its peak of excellence some 40 years later under Lully, during the reign of Louis XIV. Lully was an outstanding conductor who demanded perfection. He conducted with a cane to ensure rhythmic unity and created a balanced ensemble of violins, flutes, oboes, bassoons, and double basses. In France, the orchestra was a vehicle for the private entertainment of the nobility; during the same period, however, the first recorded public concert by an orchestra took place in London, in 1673. By the time of Corelli, a generation later, the modern violin had taken precedence over its competitors as the heart of the orchestra; viola, vielles, and lutes were rarely used except as solo instruments or for special effects.

Striving for excellence marks the history of both instrumentalists and conductors. Band and orchestra conductors featured technically accomplished instrumentalists and vocalists. Corelli, a noted performer as well as composer, is often given credit for originating the practice of matched bowing for orchestra. Alessandro Scarlatti increased the importance of the operatic orchestra, often dividing the strings into four parts and balancing them with the winds. The brasswinds became a legitimate part of the orchestra about 1720, the addition of instruments for emotional expression often marking a composer’s style. Any list of individuals important to the development of the orchestra must include Gluck. He not only made innovations in the use of instruments but also, more significantly, made radical changes in the type of music played by the orchestra. He introduced the use of the clarinet, omitted the harpsichord, and gave the orchestra music to play that was genuinely expressive and dramatic, mirroring the scenes and action of the opera. With Gluck the orchestra discarded its role as simple accompaniment and became an independent dramatic force.

Figure 1.1 1873—Leipzig, Germany: The Women’s Orchestra of Frau Amann-Weinlich

The classical era of Haydn and Mozart created the balanced instrumentation and the musical forms that have for the past few hundred years made the symphony orchestra the chief of musical structures, first in popularity with the public and greatest in challenge to the composer. During the nineteenth century, the number of orchestras multiplied rapidly in Europe (Figure 1.1) and were, along with bands, established in America as well.

At least since the 1760s, amateurs and professionals constituted the membership of both ensembles. The first symphony orchestra to be organized was the London Philharmonic in 1813. The New York Philharmonic, formed in 1842, has been in existence since that date. Several events gave impetus to the orchestra movement. One of these was the visit of the Jullien orchestra to America in 1853–1854. Louis-Antoine Jullien was a spectacular showman whose antics not only fascinated the audience but also whose music made a real and positive impact upon the American public. Another was the Germania Music Society (1848–1854) and the touring of the entertaining Steyermarkische orchestra where members kept time with cymbals on their boots. Of more lasting value and genuine artistic merit was the work of Theodore Thomas. His orchestra performed frequently, earning enough for his members to be employed full-time with daily rehearsals. He toured the country in 1863, thus enabling members’ full-time employment. Most musicians made a living by performing in various venues, pit orchestras, theaters, opera, vaudeville, pleasure gardens, circuses, accompanying touring soloists like Jenny Lind and Ole Bull, and more. Musicians were expected to be proficient on both a string and a wind instrument to facilitate employment in both bands and orchestras, a competence expected until the 1920s. In the 1880s every town and even mining camps had an orchestra. Women and Blacks formed their own orchestras. Of importance is the orchestra of the Harvard Musical Society, managed by the music critic John Sullivan Dwight who had exacting musical standards. Theodore Thomas’s interest in education led him to start a school, financed by the Nichols family in Cincinnati in 1878 for the training of professional musicians. Thomas served as the inspiration for the founding of the Boston Symphony in 1881, noted for its excellence. This excellence was made possible by the support of Boston businessman Henry Higginson, who imported European conductors and who guaranteed full-time employment for 60 musicians. Thomas also founded the Chicago Symphony, where he established a precedent of corporation support through an orchestra association. Support for other orchestras came from subscription concerts with an annual fee and profits from the audience’s eating, dancing, and drinking. Orchestras, like bands, performed music the audience wanted to hear. Thus, when the waltz was replaced by new dance styles in the 1920s, orchestras lost out to bands. The popularity of pleasure garden concerts led to the founding of summer “pops” orchestras, first by Arthur Fiedler in Boston and later to most orchestras. These provided important support for the professional performers; the expected “season” was about 20 weeks. Philanthropic support became important as audiences were reluctant to pay for music the musicians wanted to play; the orchestra was perceived as entertainment. The orchestra’s high point in the U.S., along with that of bands, may have been between 1900 and 1920. Walter Damrosch attempted to teach music appreciation using the radio and the New York Philharmonic in the mid-1920s. Federal support for some 127 symphony orchestras was provided during the 1930s depression. In the mid-twentieth century, the Ford Foundation allocated some 80 million dollars to stabilize the financial situation of major and regional symphony orchestras. This grant was critical and most orchestras were able to find support to replace this one-time largesse, thus enriching communities with professional and semiprofessional orchestras. Charismatic conductors continue to be important to the history of bands and orchestra.

Figure 1.2 c. 1520—Nuremberg, Germany: A mural attributed to various artists, including Hans Holbein and Albrecht Dürer, depicting members of the town wind band playing from a balcony

The Development of the Band

The growth of the band movement is less clearly defined. In the late sixteenth century, Venice was the center of a group of composers who wrote for brass ensembles, primarily trombones and cornetti. These ensembles performed principally in the church (Figure 1.2).

They were followed by other brass groups, usually civic or military bands, throughout Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Oboes, clarinets, horns, and bassoons were soon added. Considering the state of these instruments at the time, one would agree that their sound was primarily useful for battle commands. Bands as we know them today seem to have stemmed from the formation of the 45-piece band of the National Guard in Paris in 1789. Bernard Sarrette conducted this band for one year. In 1790 its number was increased to 70, and Francois Gossec became the conductor. Two years later the band was dissolved, but its members eventually became the nucleus of the French National Conservatory, founded in 1795.

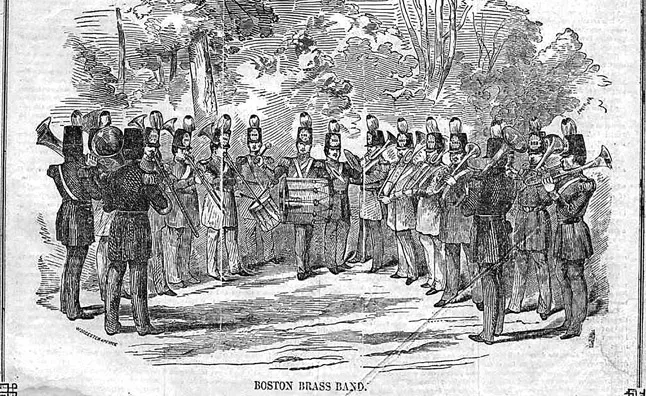

Other than the UK’s brass bands, America has been the leading country in the formation of concert bands, with groups that antedate the Paris Band of the National Guard by more than a decade. Josiah Flagg, often known as the first American bandsman, was active as early as the 1700s. The Massachusetts Band, formed in 1783, later became the Green Dragon Band, then the Boston Brigade Band (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 1851—Boston, MA: A woodcut from Gleason’s Pictorial Magazine (August 9, 1851) depicting the Boston Brass Band, which utilized exclusively over-the-shoulder brass instruments

In 1859 the Boston Brigade Band acquired a 26-year-old conductor, Patrick Gilmore, who changed its name to Gilmore’s Band, took it to war, and made it famous. He took a cue from orchestras, touring the U.S. to provide fulltime employment for the musicians. Most bands had little permanency; much depended upon the conductor and/or public support. The Allentown Civic Band, formed in 1828, one year after college bands at Harvard and Yale, still performs today; and many New England towns are able to trace an early origin; e.g., the Temple, New Hampshire town band was formed in 1799. These town bands were presumably small, comparable to the U.S. Marine Band, founded in 1798, which at the turn of the century was composed of two oboes, two clarinets, two horns, a bassoon, and a drum. The size of these bands is estimated to have been between 8 and 15 players, growing rapidly until the Civil War. Beethoven wrote his military march in D (1816) for a minimum of 32 players. To honor the visit of the Russian Emperor Nicholas to Prussia in 1838, Wilhelm Wieprecht combined the bands of several regiments and conducted more than 1,000 winds plus 200 extra side drummers. Royal visits were traditionally accompanied by impressive bands and orchestras.

The improvement of brass instruments with valves and pistons allowed for excellence in performance and increasingly a wide selection of literature. It also increased public interest in instrumental music. Competition and comparison of performance seems inherent with music ensembles. Touring European ensembles and soloists by the mid-nineeteenth century aided in establishing musical standards in the U.S. The band contest held in Paris in 1867 involved bands from nine nations. According to Goldman, the numbers played included the “Finale” of the Lorelei by Mendelssohn, “Fantasy” on the Prophet by Meyerbeer, Rossini’s William Tell Overture, the “Bridal Chorus” from Lohengrin by Wagner, plus a “Fantasy on Carnival of Venice.” Soloist virtuosity accompanied most performances; variations on Carnival of Venice continue to challenge today’s performers. Higginson’s superior Boston Symphony’s concerts in New York City established a new standard for the New York Philharmonic and a continuing comparison. Brass bands were often conducted by virtuoso cornet soloists. The model may have been the Dodworth Brass Band, arguably the best band in New York City prior to Gilmore’s reign. In 1853, two New York bandmasters, Kroll and Reitsel, began to use woodwinds with the brasses, thereby greatly expanding the band’s musical potential as well as its repertoire.

Some 500 bands enlisted in the Civil War, most as an extant ensemble. Most were discharged in a year as the men were needed to fight, although some were retained to entertain and to support morale. The real impetus to the band movement came as a celebration of peace. After Gilmore’s band was mustered out of the army, an opportunity came in 1864 to form a “grand national band” of 500 army bandsmen and a chorus of 5,000 school children for the inauguration of the governor of Louisiana. Ever the entrepreneur, Gilmore’s business acumen sensed financial possibilities as the event appealed to patriotism and education. Three years later, he aided in organizing a World Peace Jubilee on an even grander scale but with less financial success. The finest musical organizations of Europe participated, however, attracting the public and popularizing better music. The visiting European groups dazzled the audiences with their skill; it was obvious that American bands and orchestras were no match for them.

American bands improved rapidly in the second half of the nineteenth century. Instruction books were published by mid-century, and as early as 1816 West Point had added an instrumental teacher to the faculty who was also the band director. Gilmore took over the leadership of the 22nd Regimental Band in 1873 and directed it until his death in 1892. He was succeeded by the unlikely personage of Victor Herbert, whose well-loved melodies seem to have been little influenced by the military march. Herbert also conducted the Pittsburgh Symphony. From 1880 until 1892, John Philip Sousa conducted the Marine Band and gave it a national reputation for excellence and original popular marches. Sousa and Gilmore toured extensively, bringing fine performances of both great music and popular music to audiences who had little other opportunity to hear professional concerts. Many fine local bands sprang up. Their repertoire included transcriptions of orchestral favorit...