![]()

|

CASE 1

PRIMARY CILIARY DYSKINESIA

|

|

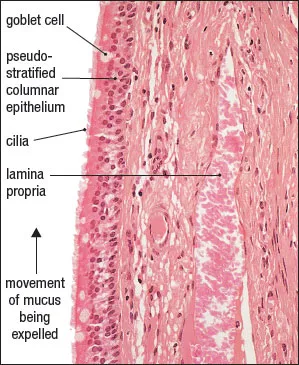

The lung is kept free from microorganisms and other inhaled particles by several innate immune mechanisms. These include the turbinate bones in the nose, which are coated with sticky mucosa to entrap large inhaled particles. Particles that are able to move beyond the turbinate bones are removed by a functional epithelium in the bronchi and bronchioles of the respiratory tract, consisting of ciliated epithelial cells and mucus-producing goblet cells. Together, these structures form a defense mechanism (called the mucociliary escalator system) that prevents the movement of inhaled particles and microorganisms into the lungs. Pathogens are trapped in the mucus layer, and the rhythmic beating of the cilia then moves this mucus “blanket” towards the pharynx, where the trapped material is expelled (Figure 1.1). When the cilia are structurally defective, they are not able to create the “wave” of motility necessary for defense, and they thus pose a threat to pulmonary health.

Figure 1.1 The pseudostratified epithelium lines the trachea and consists of ciliated columnar epithelial cells interspersed with goblet cells that contain mucus. The mucus is secreted into the airway lumen, where the cilia create a movement towards the pharynx. The mucus-trapped foreign particles are expelled by the cough reflex. (From Aughey E and Frye FL [2001] Comparative Veterinary Histology with Clinical Correlates, 2nd ed. Courtesy of CRC Press.)

THE CASE OF ANGEL: A YOUNG DOG WITH CHRONIC COUGHING AND REGURGITATION

SIGNALMENT/CASE HISTORY

Angel is a 7-month-old spayed female Old English Sheepdog who was purchased at 3 months of age by her owner, began coughing shortly afterwards, and has continued to do so ever since. She sometimes expels froth during her fits of coughing, and she also vomits and regurgitates during coughing episodes and after meals. She has previously been seen by a veterinarian for dehydration, and has been on and off antibiotic treatment for several months. She is currently on Clavamox 62.5 mg twice a day and Pepcid, and has received all of her core vaccines, but is not on a heartworm preventative at present. During a recent episode of acute respiratory distress that occurred when the owner ran out of antibiotic, the referring veterinarian identified areas of consolidation in Angel’s left cranial lung lobe.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

On physical examination, Angel was bright and alert (Figure 1.2). Her temperature was 102.6°F (high normal) and her respiratory rate was high at 85 breaths/minute. She did not have any heart murmurs, and her mucous membranes were pink, with a capillary refill time of less than 2 seconds (normal). On auscultation her lung fields were clear, but a cough was elicited by tracheal palpation. Presumably the current antibiotic therapy had resolved the consolidation previously identified in her left lung lobe.

Figure 1.2 Angel at 7 months of age. (Courtesy of iStock, copyright Sasha Fox Walters.)

TOPICS BEARING ON THIS CASE:

Innate immunity of the respiratory system

Mucociliary escalator

Inherited defect predisposing to recurrent pneumonia

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

In the absence of an obvious acute infectious disease, as indicated by lung auscultation and lack of fever, causes of a chronic cough could include allergic bronchitis, cardiac disease (including heartworm infection), and—due to the early age of onset and chronicity of the clinical signs—congenital abnormalities in the respiratory tract, such as ciliary dyskinesis. Familial ciliary dyskinesis has been observed in the Old English Sheepdog. Additional possible causes of vomiting and regurgitation include megaesophagus, neoplasia, and chronic gastritis.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS AND RESULTS

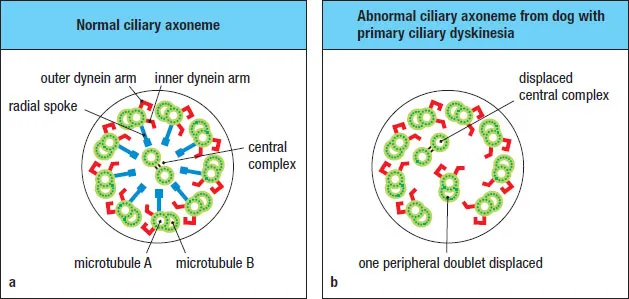

Thoracic radiographs taken during the most recent acute episode showed alveolar infiltrates, primarily in the cranial lung lobes. No evidence of megaesophagus was found. Abdominal radiographs were unremarkable. A complete blood count (CBC) and chemistry panel showed an elevated white blood cell count of 31,680/μL with a neutrophilia of 26,643/μL. Neutrophils were the predominant cell type. Taken together, these data support a diagnosis of bronchopneumonia. Additional studies to evaluate Angel’s mucociliary apparatus were performed based on the history of recurrent bronchopneumonia, which is resolved by antibiotic treatment but recurs once antibiotic therapy is discontinued. These tests included bronchoscopy, bronchoalveolar lavage, and a technetium scan to evaluate ciliary motility. Bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage revealed a mildly inflamed bronchial mucosa, with a moderate purulent and eosinophilic inflammation. Cultures of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid grew only small numbers of mycoplasma, suggesting that the currently ongoing antibiotic therapy had suppressed bacterial growth. Mucociliary function testing by technetium scanning showed a lack of mucociliary escalator function, consistent with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Biopsies of nasal and tracheal mucosa submitted for electron microscopy showed cilia with an abnormal structure (Figure 1.3).

DIAGNOSIS

Angel was diagnosed with bronchopneumonia due to primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD). Although electron microscopic evaluation of the ciliary structure is not performed for all reported cases of PCD in dogs, in those cases where it is undertaken it is reported that abnormal dynein arms are most common, as well as abnormal orientation of the central microtubule pair. PCD should be considered in cases of recurrent antibiotic-responsive pneumonia, particularly in a purebred dog.

TREATMENT

There is no procedure for repairing the cilia, and therefore the patient must be treated symptomatically. This involves providing appropriate antibiotics and supportive care. Patients with PCD are encouraged to cough to move the mucus up and out. Percussion can be helpful, and adequate hydration is critical so that the mucus stays fluid. Human patients in rare and extreme cases have needed a lung transplant, but this is not currently an option in dogs.

Figure 1.3 (a) The structure of a normal cilium, which has a central pair of microtubules surrounded by nine doublets. Each doublet has inner and outer dynein arms and radial spokes. The presence of these components in the appropriate structure is required for proper ciliary function. In cases of primary ciliary dyskinesia there is a genetic abnormality that disturbs this normal assembly. (b) An abnormal cilium from a dog with PCD, with displacement of the central microtubule complex and displacement of one of the outer doublets. This is only one example of several ciliary abnormalities that have been described in PCD, including absence of the dynein arms.

PRIMARY CILIARY DYSKINESIA

PCD is an inherited condition in which the cilia are not effective. Originally called “immotile cilia syndrome,” it is now referred to as primary ciliary dyskinesia because the cilia are rarely completely immotile—most cases have cilia with some degree of motility. However, due to structural defects this motility is aberrant and weak, and is not effective in creating a wave of motility. The case history for Angel is quite typical, with pneumonia that is responsive to antibiotics recurring after cessation of treatment.

A prominent study that reported PCD in a litter of English Pointers reviewed data on PCD presentation in all nine of the puppies. The age of presentation ranged from 7 weeks to 14 months, as expected for a primary inherited defect. Nasal discharge, bronchopneumonia, and leukocytosis were common. A large study on Old English Sheepdogs with PCD identified a genetic mutation affecting the CCDC39 gene, causing absence of a functional CCDC39 protein that is involved in the motility of cilia (it has an important role in the assembly of the dynein inner arm complex, and is responsible for regulation of the ciliary beating). The dogs in which this recessively inherited mutation was expressed had abnormalities in the central microtubules, and like the English Pointers and Angel they had recurrent nasal discharge, cough, pyrexia, leukocytosis, and bronchopneumonia. The discovery of this genetic link to PCD has provided breeders with the ability to scan the genome for this defect and perhaps ultimately eliminate it from the breed.

COMPARATIVE MEDICINE CONSIDERATIONS

In humans, PCD is a rare disease and is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. As in dogs, it is characterized by reduced or absent mucus clearance from the lungs. Other organ systems that contain cilia can also show associated dysfunction, including the ear (causing deafness) and the reproductive tract (causing infertility). Renal fibrosis is another commonly associated pathology. Hydrocephalus and abnormal sternebrae are also sometimes associated with PCD in human patients. Some similar abnormalities have been noted in canine patients, including abnormal sternebrae, renal fibrosis, situs inversus, and hydrocephalus.

In human patients a variety of ultrastructural abnormalities have been identified by electron microscopy of the cilia, namely absent or abnormal dynein arms, absence of radial spokes, transposition of microtubules, and random orientation. The majority of human patients with PCD have ultrastructural defects in the proteins that form the cilia and provide their motility. As in dogs, mutations have been identified in genes coding for proteins that form the dynein arms of the cilia. One form of the disease is called Kartagener syndrome, which is defined by the triad of situs inversus, rhinosinusitis, and bronchiectasis. However, the majority of PCD diagnoses, defined by irregular, ineffectual function of the cilia, are not classified as Kartagener syndrome.

Questions

1. This case has focused on the role of the mucociliary apparatus in prevention of infection of the lungs. What other structures or cells are involved in keeping the lungs free from inhaled particles and bacteria?

2. What organs other than the lungs are often affected in a patient with ciliary dyskinesia, and what is the effect of the non-functional cilia on these organs?

3. Angel had been spayed prior to being diagnosed with ciliary dyskinesia. If she had instead been bred to another dog carrying the same mutation, in a litter of four puppies how many individuals would you expect to have the disorder?

Further Reading

Merveille AC, Battaille G, Billen F et al. (2014) Clinical findings and prevalence of the mutation associated with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Old English Sheepdogs. J Vet Intern Med 28:771–778.

Morrison WB, Wilsman NJ, Fox LE & Farnum CE (1987) Primary ciliary dyskinesia in the dog. J Vet Intern Med 1:67–74.

Wilsman NJ, Morrison WB, Farnum CE & Fox LE (1987) Microtubular protofilaments and subunits of the outer dynein arm in cilia from dogs with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Am Rev Respir Dis 135:137–143.

![]()

| CASE 2

LEUKOCYTE ADHESION DEFICIENCY | |

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (neutrophils) are formed in the bone marrow and then enter the bloodstream, where they circulate for a short time. In response to signals from sentinel cells, pathogens, and cytokines, these cells will move out of the blood vessels and into the tissues, where they can act as phagocytes to protect the host from bacterial infection. This movement is dependent upon correct ...