eBook - ePub

Performance-Based Medicine

Creating the High Performance Network to Optimize Managed Care Relationships

- 294 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Performance-Based Medicine

Creating the High Performance Network to Optimize Managed Care Relationships

About this book

With healthcare making the transition from volume-based reimbursement programs to value-based approaches, understanding performance measurement is vital to optimize payment and quality outcomes. Performance-Based Medicine: Creating the High Performance Network to Optimize Managed Care Relationships guides readers through the maze of definitions and

Information

Chapter 1

Integration and HMOs: How Did We Get This So Wrong?

From the very beginning of the discussions about integration, the examples used were provider-owned entities such as Kaiser, Health Partners, Intermountain, and other health maintenance organizations (HMOs), and all were seen as seamless enterprises able to control price and volume because the owners were actually involved in the production of the product. In effect, HMOs were the very first integrated systems tying together the delivery and financing of care. This binds the patient both in terms of clinical care and affordability, knowing that the insurance plan would always offer the benefits and a place to receive those benefits.

This guarantee or covenant of caring is what built HMOs in the early 1970s and drew in thousands of consumers who trusted their physicians and their health plan.

This is totally separate from the current situation where the largest HMOs are not HMOs at all but rather insurance companies who finance care after an accident or illness has occurred. These insurance companies saw HMOs as a product line with preventive services covered and no deductible.

A product with no means to control volume or quality of medical services was produced. This, instead of improving care realigns discounted payment to push down providers’ incomes unless providers follow a dizzying array of rules. Many of these rules became so blatant that, in a successful lawsuit against United Health Plans in Chicago, the plaintiff physician proved that he was acting on orders from United, and the judge ruled that this was no longer a contractual relationship but rather one of employee/employer. United Health was accused of practicing medicine. Many suits before and after have tempered the relationship between plan and provider to distance this relationship, but in few cases did the provider network actually understand that if they organized independent of the insurance company they could not only control and negotiate quality standards but also put some of the savings back in their own pocket versus giving it all to the insurance companies.

This provider organization goes by many names, going back to accountable health organizations (AHOs), now accountable care organizations when we were talking about managed competition. A new entity called provider sponsored organizations (PSOs) was promoted to create a way to integrate payment and quality measurement. As plans became larger, hospitals formed increasingly larger cartels to try to bring reimbursement up to a higher level or the HMO would be forced to lose the contract and have no providers and, therefore, no enrollees in a given territory. Many of these cartels, Physician Hospital Organizations (PHOs), and provider networks were subject to antitrust investigation for price fixing and attempting to conspire to force providers to accept terms and conditions that were not beneficial to the community or to the plan.

In all of these variations of integrated systems and integrated delivery networks (IDNs), the thought of somehow creating a structure with negotiating power became the single-minded goal versus actually improving care and rearranging process and outcome.

By removing waste from the system of uncoordinated care and nonfunctional silos of administrative costs, the services could be offered at a lesser price. By reducing the unnecessary services of both inpatient and outpatient care while still assuring that necessary care would be available, providers and payers and patients would save money and get great care more rapidly.

This goes back to the original HMO concept. The HMO became the reorganizer of services and overlaid some of it specifications and performance measures on top of the traditional payer provider agreements.

Provider-sponsored plans had a natural advantage as we said earlier, because their goal was to remove waste and increase quality. By doing this, the provider and the HMO they owned could sell the benefit plan at a lesser premium than a competing insurance plan. In addition, the original, or as I will call it, the Classic HMO, was organized to then offer more benefits with these savings. Initial savings from covering physical exams and early periodic treatment for infants all paid for the extra benefits offered.

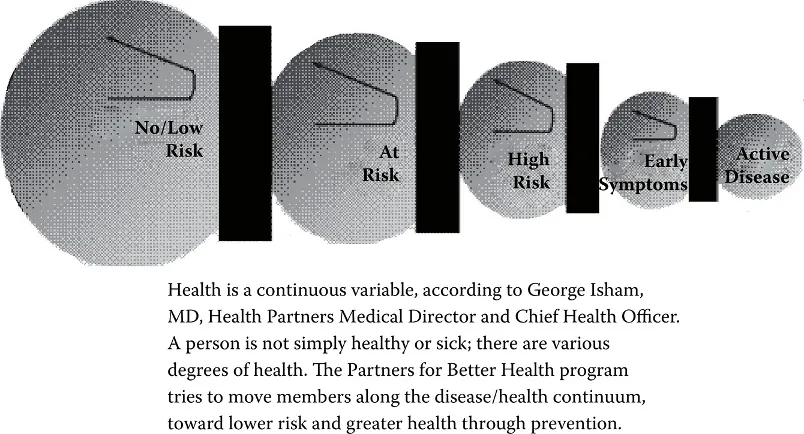

In effect, prevention cost the plans nothing as long as they could use this patient health status information as a foundation for the case management and coordination of care. This allowed each patient to have an early warning system as they moved from high risk to chronic disease. Everything that the plan could do to prevent this potential high-risk patient to stay out of the high-risk category had to be done (see Figure 1.1). Otherwise, premiums started to climb and soon the high-risk and chronically ill patient population would force the plan out of business because the only remaining patients in the plan had expensive illnesses and it would price itself out of the market.

Figure 1.1 The disease–health continuum. (From George C. Halverson and George J. Isham. Epidemic of Care: A Call for Safer, Better, and More Accountable Health Care. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003.)

It all comes down to three large issues that have led us to performance based contracting. They are reimbursement, coordination, and performance.

Reimbursement

The traditional medical practice and hospital makes more money by generating more services for which they can bill. This “production” mentality of creating more and more sophisticated services with admittedly better acuity and precision added to the cost of care. When a fixed priced payment system was introduced, physicians and hospitals both fought it because they did not understand that higher income was usually followed by greater expense. An example follows:

Community-Acquired Pneumonia Story from Intermountain Health System in Salt Lake City, Utah

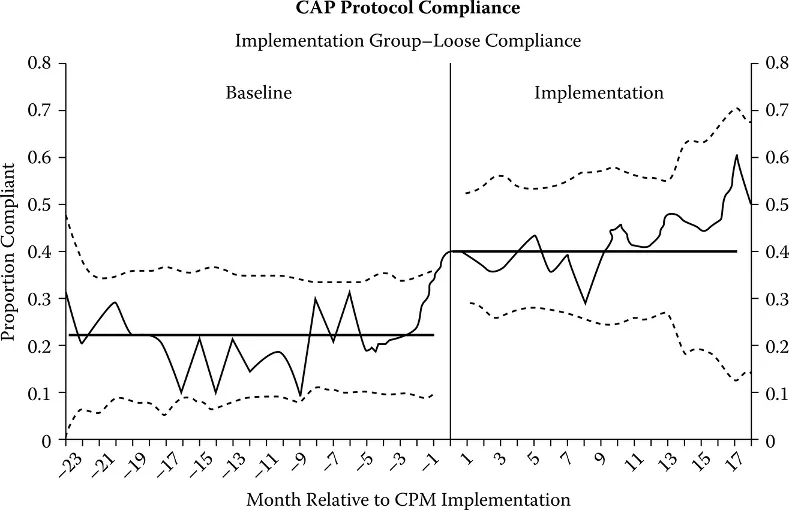

The community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) Protocol (Figure 1.2) revolved around saving money and saving lives by having physicians get antibiotics to patients quicker. As the proportion of compliant physicians improved, the implementation created positive outcomes, to which the hospital’s CEO said, “Show it to me in my budget.”

Figure 1.2 CAP protocol compliance.

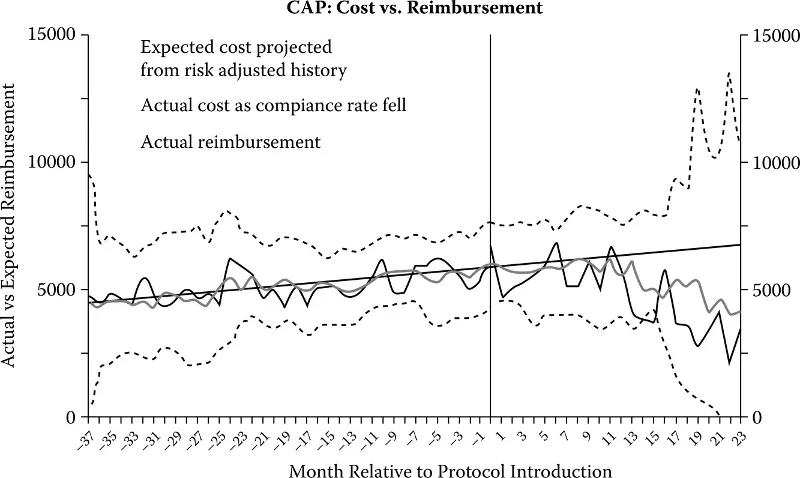

Figure 1.3 shows the real truth, and that is that as complication rates fell the net income from revenue fell.

Figure 1.3 CAP: Cost versus reimbursement.

In simple terms, the complicated patients being seen with respiratory problems and needing to be put on a ventilator and billed as Diagnostic Related Group (DRG) 475 were slowly moving backwards into DRG 89 because they were being caught early and getting antibiotics and being sent home. The problem was that Intermountain was reimbursed $16,400 for DRG 475 for something that generally cost them $15,600. DRG 89, however, cost Intermountain $5,200 to provide but Medicare only reimbursed $4,800. So you can see Intermountain was replacing procedures with a net income gain of $800.00 with procedures that have a $400.00 income loss.

A discussion of these phenomena was presented in the New York Times by Reed Abelson some years back. It said that, “We as hospitals and physicians are actually rewarded to keep people sick versus get them well because there is more money in keeping them sick.”*

This, Dr. Brent James, medical director of Intermountain Health System, believes, was the trigger that started the entire pay for performance movement. Government and private payers are using this argument with employers and patients to prove that the system has problems and will not reform itself.

Well, what can be done?

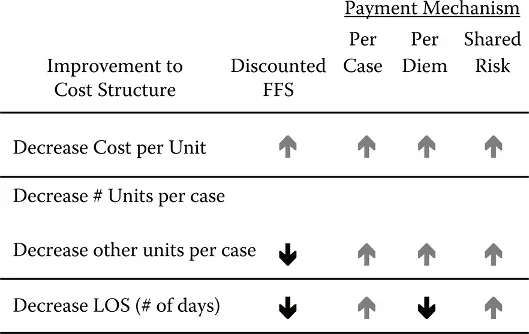

Figure 1.4 shows how different methods to lower costs affect payment. Reducing units, cases, etc., all can cut costs, but they also cut net income in many cases.

Figure 1.4 Impact on net income.

Figure 1.4 also shows the Intermountain experience as 80% of the payments come to them under discount or case rate.

What it says in Figure 1.4 is that the payers are making a large margin on these services because they are not being managed. The more we reengineer our hospitals to be more efficient and effective, the more savings are created for the insurer.

The conclusion one reaches is that the only way that providers are going to survive in the future is to create a carefully structured, shared-risk arrangement with payers or own the payer themselves. That is, if we let insurance companies run the numbers and tell us where our losses are, we are opening the piggy bank of net profit and cash flow to organizations who could create a problem for us.

* Reed Abelson, While the U.S. Spends Heavily on Health Care: A Study Faults the Quality, New York Times, July 17, 2008.

This explains why many integrated systems and hospital-owned HMOs fail. Hospitals need to have data on a product line basis to survive. Not every product line does well because as complications arise so do expenses. These expenses all have an impact on net revenue when connecting them to reimbursement.

Margins between cost and charges were narrower, which required more volume. When that volume was not present the temptation was to increase complex services even though there was not a good clinical rationale to use it.

Many hospitals and physicians continue to fight words like capitation and fixed fee schedules. They see these as barring them from income to repay their investment in equipment, staff, and training for these sophisticated procedures. This misses the mark as to how performance-based contracting is changing things with a focus on managed care companies and employers seeking to contract for best-in-class services in a given community versus merely contracting with a hospital. Because hospitals have become accustomed to using loss leader services to bring in volume and then cross-subsidizing departments and services to balance their books, the new vision is that each of these services will need to be captured by specialty and department and then negotiated as an Episode Treatment Group (ETG) or Episode Resource Grouping (ERG).

Reimbursement is a key changing factor because of the emphasis on performance and is a critical part of actually developing a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Integration and HMOs: How Did We Get This So Wrong?

- 2 Performance Measurement: A Science with No Followers

- 3 Reimbursement: From Fee for Service to Risk Adjusters

- 4 Early Pay for Performance

- 5 Performance Language and Practice

- 6 Reengineering

- 7 Challenges

- 8 International Reform

- 9 Getting Started

- 10 The Future of Performance-Based Medicine

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Performance-Based Medicine by William J. De Marco, MA, CMC,MA, CMC, William J. De Marco in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.