1

London/Berlin

The “division of the subject” is not a warlike expression, although the military sense of the word “division” can introduce the idea that such division is the only weapon at the subject’s disposal for becoming and remaining sensitive to the real. This real, indeed, only becomes such by resisting the linguistic domestication that, like time for Baudelaire (1857, p. 20), is an “enemy that gnaws our heart”. “Division” and “splitting” are translations of Freud’s German term, die Spaltung, a word that appears late in his work, in his article, “The Splitting of the Ego in the Processes of Defence” (1940b). The epistemic event signalled by this term went unnoticed for a time; splitting was first understood as a supplementary defence mechanism (although the Kleinians were more perceptive on this point than the followers of Anna Freud). Nevertheless, it prefigures what I do not hesitate to call, in a proposition that owes everything to Lacan, a new treatment of castration. It should be noted that the article on the Spaltung is more or less contemporaneous with “Analysis Terminable and Interminable” (1937), the article in which Freud introduced the expression, the “bedrock” of castration.1

Post-Freudianism does not distinguish between castration and splitting, and a part of “post-Lacanianism” seems to have repeated this lazy reading. Yet the difference between them is decisive. Lacan (1967–1968) began to theorise this in his 1967–1968 seminar,

L’acte psychanalytique. What is in question is a difference that is synonymous with that between lack (which opens up the possibility of not lacking) and loss (which is irreversible) and especially between the negativisation of the phallus (-φ) and the barred subject (

). The latter implies the production of an object, called the object

a, which has no representation; this situates it radically outside any representation in language. The end of an analysis lies in accepting this division and mourning one’s castration, inasmuch as the latter, as we have just seen, preserves the possibility of filling in lack (by sex, money, power). This

idea will be decisive for this section of the book: because the capitalist discourse rejects castration, its effect is

a fortiori to mask the division of the subject.

Two couples – Robert Louis Stevenson’s Jekyll and Hyde, in the Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), and Bertolt Becht’s Joan Dark and Pierpont Mauler, in Saint Joan of the Stockyards (1938) – show us this refusal of subjective division, in the form of a new literary myth that ultimately includes both the material for the ideology of this refusal and a critique of that ideology. It seems incontestable and relatively easy to demonstrate that capitalism, in the form of the individualism that derived from the French Revolution, projected its lethal shadow upon both Stevenson and Brecht. What this myth concerns is not the kind of contradictory debate between libertinism and virtue, which can be set up between Sade and Robespierre, Mirabeau and Saint-Just, figures who exist as entities outside their pairing and each of whom claims the privilege of having been faithful to the revolution. Instead, these couples – Jekyll and Hyde, and Mauler and Dark – constitute a single unit, and their sundering into two separate people prevents either of them from being split; such a splitting would involve accepting the dialectic of the relation to the unconscious. Far from being the recognition that the unconscious has an intangible and inaccessible kernel, it is purely and simply the rejection of the very hypothesis of the unconscious. Hyde, because he has been cut away from his unconscious, which is found in Jekyll, escapes from the latter’s control; this proscription of the unconscious enables us to hear the silence of the drives.

Joan Dark has also been cut from her unconscious, which exists in Mauler, to whom she lends her innocence, and she does not want to question her own relation to this innocence. This position leads her to betray the cause that she has sincerely adopted, and she does so without even realising it. Pure evil (Hyde) like pure good (Joan Dark) are fictions of the ideology that enables capitalism – or more precisely, its discourse – to breathe; this discourse is the linguistic armature without which the capitalist mode of production would collapse.

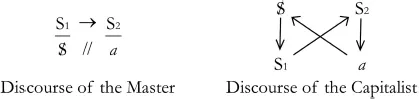

I shall refrain from giving an exposition of the four discourses, as Lacan forged them in The Other Side of Psychoanalysis, and the capitalist discourse, which derives from one of these four – the discourse of the master – until a later section, entitled “UMHA [University-Master-Hysteric-Analyst]”. However, in order to make the relevance of its epistemic use in this first part understandable, I must note that the specific characteristic of the capitalist discourse is an exemption from the form of the four discourses. These discourses – of the university, the master, the hysteric and the analyst – are explicitly constructed in terms of the principle of a “barrier” of jouissance (Lacan, 1991, p. 108); within these discourses, this barrier prevents the place of the production from reaching that of truth. In order to forestall any misunderstanding, I shall note that this major thesis does not signify an absolute scepticism; it simply means that truth, which should not be confused with the real, can be touched only through the negative path of falsification. In no case is it possible to say the truth about the truth, or to hope that the “whole truth” can be said, to quote one of Lacan’s (1974b, p. 3) canonical formulations.

What characterises the capitalist discourse, on the contrary, is the lifting, or rather the annulment of this barrier. Its spirit is best summarised by the slogans coined by the sinister Prime Minister of the French July Monarchy, François Guizot – “Everyone is a capitalist [Tous capitalistes]!” and “Enrich yourselves [Enrichissez-vous]!” – who took advantage of the legal equality between individuals in order to authorise the idea of a potential equality that would exist at a level of having possessions, an equality that capitalism would offer. I would like to argue immediately that the secret that provides the foundation for this lie is found in the capitalist discourse: by annulling the barrier of jouissance and thus allowing people to glimpse the mirage of a consumption that would saturate desire (a possible definition of jouissance), this discourse asserts that the object a – the surplus object, of which we can fundamentally have no idea – is equal to money, which can be counted and entered into financial records.2 This enables us to understand why Lacan credits – or discredits – Marx with having given a foundation to capitalism by taking surplus jouissance, the object a, as a surplus-value, thus making it subject to an energetics and contradicting the principal axiom of psychoanalysis: there is no energetics of jouissance.3

The alchemy of capitalism does not transform desire into jouissance, yet in making the plastic carrot glimmer with desire, capitalism keeps sharpening it until it has been worn down to nothing, as is demonstrated by the various addictions that are responses to this death of desire.

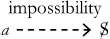

I shall now give the briefest sketch possible of the logical bases of Lacan’s discourses. In the matheme of the capitalist discourse, as I shall argue in detail later, there is a vector that goes from

a (surplus-jouissance) to

, the subject.

4 As with all scientific notions, even when it is possible to give definitions and formulas for them, this relation is not absolutely transparent: it cannot be reduced to a denotation that would make it entirely and eternally intelligible. This same arrow is also found in the analytic discourse, where, however, it is marked as impossible.

This can be read from right to left: the desire of a subject – in this case, the analysand – cannot (hence the impossibility) find its satisfaction in the object a – in this case, the analyst – which nevertheless causes the subject’s desire. If analytic treatment can be described as the analysand’s mobilisation, through transference, of surplus-jouissance, a “profit” of jouissance that feeds his/her desire to speak, then at the end of analysis, this jouissance proves to be vacuous, and this “profit” becomes the commemoration of an initial and founding absence: that of a jouissance that could saturate desire. In reality, as I shall argue later about the analytic discourse, this absent jouissance is the Other’s. The jouissance that I impute to the Other is nothing more than a product of my thought, for any jouissance that I experience can only be what affects my body. I cannot reach jouissance in the Other’s body. The genius of obsessional neurosis is to support this jouissance of the Other by pure thought, while the genius of hysteria is to posit that a lack of satisfaction is the condition for desire. The analytic discourse is able to turn these two neurotic creations around by turning the fantasy around, because it is constituted on the basis of the impossibility for the subject to experience the jouissance of the Other (God, the parents, the partner, etc.).5

The capitalist discourse presents us with a route that can be repeated indefinitely, a route that, in a certain way, makes repetition present. This discourse derives from the discourse of the master. In the latter discourse, with the vector that goes from S1 to S2, the master commands the slave, but the slave is the one who knows, a knowledge that enables him/her to act. In this respect, the transposition of this couple into that of the capitalist and the worker is not unwarranted, since what intervenes in production is the certification (S2) of labour-power. What gives this S1 its ability to command is not knowledge but money. This money will be valorised by the investment and cathexis of knowledge in production.

The worker produces, and in the Marxist sense, produces surplus-value. Within capitalism, labour-power becomes a commodity. Thus, surplus-jouissance can take the form of surplus-value. This surplus-value (Mehrwert) is the extra value produced by the wage-earner during his/her overall labour time, once the value of his/her labour-power has been reproduced during the earlier hours of the working day. As Marx notes in the Grundrisse:

if the worker needs only half a working day in order to live a whole day, then, in order to keep alive as a worker, he needs to work only half a day. The second half of the labour day is forced labour; surplus-labour. What appears as surplus value on capital’s side appears identically on the worker’s side as surplus labour in excess of his requirements as worker, hence in excess of his immediate requirements for keeping himself alive.

(Marx, 1939, pp. 324–325)

Hyde and seek

In the capitalist discourse,

(the subject) and S

2 (knowledge) constitute a couple in which each element is

sundered [

scindé], rather than

split [

divisé] from the other. I am using the term “sundered” as the name of a process in which the dialectic that occurs in splitting is absent. This sundering is the true subject of Robert Louis Stevenson’s extraordinary text, the Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. This book appeared in 1886, three years after Marx’s death, and two years before the article

on hysteria that Freud (1888) wrote for Villaret’s medical dictionary. This narrative deserves to be considered as a new myth because it is different from the problematic of the double, which is characteristic of German “dark romanticism”. Just as Hyde is not Jekyll’s double, so Jekyll is also not Hyde’s double. They are two sundered entities rather than a split subject.

It is true that Jekyll himself uses the word, “double” in the succinct notes that he keeps on the experiment in transformation (see Stevenson, 1886, p. 123). Yet there is a decisive reason not to rank Stevenson’s story within the enormous body of literature concerning the double produced during the nineteenth century: Hyde and Jekyll never encounter one another, for although they are sundered, they are also the

same. They are both enclosed within the “fortress of identity”, as Stevenson (1886, p. 111) says. Naturally, Jekyll is situated in the place of S

2 and Hyde in. Jekyll is a doctor, a man of knowledge, like Faust. Yet Doctor Faust triumphs where Jekyll fails. If a diagnosis were required, one could say that Jekyll and Hyde together are a

single schizophrenic. Yet what is important is that, during the very period when the process of constituting the individual had been achieved and the metaphor of the organic social body had become obsolete, Stevenson’s story brought to light an individual sundered from himself, in the form quite exactly of a

subject who has been cut from his unconscious:

// S

2.

This is one of the keys to the book: Jekyll is Hyde’s foreclosed unconscious. In other words, Hyde should be considered as the hero, whose inability to know anything about his unconscious is the tragic weakness that constitutes the story’s motive force and novelty. His access to the unconscious has been radically closed because the barrier of jouissance has been lifted and the unconscious ends up going solo. If the unconscious, like Jekyll, is in S2, this means that, contrary to the received psychoanalytic idea that Hyde is Jekyll’s unconscious, it is Jekyll who is Hyde’s unconscious. Because Jekyll is the unconscious, which is closed in the capitalist discourse, Hyde becomes the drive. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde are the emblematic figures of this “sundering”. They could even become its eponym, if we keep the game of hide and seek in mind, since Hyde’s name is obviously a punning reference to this game.

Stevenson, who came from a family whose men had traditionally been builders or engineers of lighthouses, wrote this tale at the age of 36. The kernel of the story emerged in a nightmare that he had had a year before, from which he had been awakened by his wife, Fanny, frightened by his screams. He wrote a first narrative based on this nightmare, which he then destroyed after a violent argument with her; she objected to it because it did not include any moral.

This tale has a precedent in Stevenson’s work: an early play written with William Ernest Henley entitled Deacon Brodie, or the Double Life (1892), which was inspired by a real event. By day, Brodie was a deacon and cabinet-maker; by night, he was a burglar. The fact that he is a deacon – and thus charged with the distribution of alms – already indicates that Stevenson is concerned more with questions of money than with neoromantic narratives of doubles. It is not irrelevant to note both that his father was a rigorous and intransigent Calvinist and that, according to his own statements, he wrote his tale to pay his debts to “Byles the butcher” (see Dury, 2005, p. 9). It is also worth noting that Stevenson was once struck by reading an article on the subconscious. All of these matters converge on an emphasis on a conflict between good and evil, in which problems of money and the “subconscious” come into play in an entirely new way; the result is a new configuration that goes beyond received ethical conceptions.6

I have chosen the term “sundering” in order to accentuate the incompatibility between two entities, which belong, nevertheless, to a single personality. Entzweiung [division, split, rupture, rift], the term that Freud uses in the article, “Splitting of the Ego in the Process of Defence”, would have been appropriate if I were writing in German. “Two divide into one” – a reversal of Mao Zedong’s (see 2007, p. 196, note 19) definition of dialectic – could also be appropriated ironically. For that matter, the lacerating “schism [scission]” of the French psychoanalytic movement in 1953, in which Lacan and other notables broke away from the Société psychanalytique de Paris [Paris Psychoanalytic Society], could be described as an institutional sundering. Lacan, by analogy, would, of course, be Mr. Hyde (the drive) and the Société psychanalytique de Paris would just as incontestably be the unconscious. Let us hope that this institute will not lead to Lacan’s “suicide” – which, in my little analogy, would involve the transformation o...