1

INTRODUCTION TO THE BOOK

Crowdfunding, as a source of early finance, has attracted increasing interest from economists, management scholars, and political scientists concerned about its impact on entrepreneurial activities. Over the past 5 years, a great deal of research has been published on crowdfunding, from a range of perspectives.

The goal of the present book is to systematically integrate crowdfunding in the entrepreneurial finance literature and extend current debate on crowdfunding to include how it can become a strategic tool for entrepreneurs, to develop and grow their ventures and provide vital access to finance.

The chapters in this book focus on the post-funding phase of equity crowd financing. Relying on original qualitative and quantitative empirical evidence on UK firms that have searched for equity crowdfunding, this book provides insights into the value-added provided by crowd investors after the initial fundraising event and the post-funding performance of crowdfunded firms.

The book is organised in two parts that address interrelated topics. Following this introductory chapter, the first part of the book, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, describes crowdfunding and the most popular crowdfunding models. It offers an up-to-date account of the relevant research findings and analyses the geography of crowdfunding, including fundraising patterns worldwide.

Chapter 2 introduces the concept of entrepreneurial finance, differentiating among the stages of new venture development, and the available sources of finance. It presents the crowdfunding phenomenon and provides a classification of the most popular crowdfunding types and a description of the three main actors in the crowdfunding process. In the context of these actors (firm creator, funders, and crowdfunding platform), the focus is on creators’ and funders’ incentives and disincentives, in the former case for seeking crowdfunding and in the latter case for deciding to invest. The chapter concludes by outlining the steps in the crowdfunding fundraising process.

Chapter 3 provides a more detailed picture of crowdfunding and a review of current work on the factors associated to fundraising success, across different crowdfunding models.

Chapter 4 presents and compares the evolution of crowdfunding around the world, examining three specific markets – Europe, America, and Asia-Pacific. It explores the effects of formal institutions, such as legal frameworks, and informal institutions, such as culture, on differences in the adoption and development of crowdfunding across European countries.

The second part of the book, Chapter 5, Chapter 6, Chapter 7, focuses on equity crowdfunding. Drawing on original qualitative and quantitative data on equity crowd-funded companies in the UK, this part of the book investigates the value-added services provided by crowd investors. It considers crowdfunding as initial seed funding and describes and discusses whether and under what conditions equity crowdfunding facilitates entrepreneurs’ performance and subsequent access to external financial resources.

Chapter 5 opens with a detailed description of the equity crowdfunding phenomenon in Europe and an in-depth analysis of the two most popular platforms in the UK, Crowdcube and Seedrs, to highlight their main differences. Next, drawing on original qualitative data on UK companies that have used equity crowdfunding, Chapter 5 discusses the advantages and disadvantages of this form of funding, from the point of view of both entrepreneurs and investors.

Chapter 6 provides an up-to-date review of the literature on equity crowdfunding and examines the post-funding phase and how entrepreneurs can leverage the crowd to obtain additional, non-financial benefits such as knowledge and networks.

Chapter 7 reviews the most recent research on the performance of crowdfunded companies and how this form of funding enabled access to additional finance. It provides empirical evidence on the performance of crowd-backed companies in the UK, based on data on over 200 companies that were successful in obtaining equity crowdfunding.

Chapter 7 concludes the book with some final reflections and suggestions for future research on this new exciting topic.

The first part of this book provides a general introduction to crowdfunding. Chapter 1 introduces the book and provides a brief description of the key topics covered in each book chapter. Chapter 2 introduces the concept of entrepreneurial finance, differentiating among the stages of new venture development and the sources of finance available. Chapter 3 provides a state-of-the-art review of current research on crowdfunding, highlighting the success factors related to crowdfunding campaigns. Chapter 4 investigates adoption of crowdfunding across Europe, America, and Asia-Pacific regions, looking at explanations for differences linked to formal institutions such as legal framework, or informal institutions such as culture.

2

FINANCE FOR ENTREPRENEURSHIP

An introduction

This chapter reviews the alternative sources of financing available to entrepreneurs, highlighting their differences and their roles in the financing cycle for new ventures. It provides a description and general overview of the crowdfunding phenomenon, the different crowdfunding types in use, such as donation, reward, lending, and equity crowdfunding, and actors and stages in the fundraising process.

2.1 Entrepreneurial finance landscape

Entrepreneurial finance is a recently emerged research field, positioned at the intersection between entrepreneurship and finance. The notion of entrepreneurship dates back to 1775 when Richard Cantillon defined an entrepreneur as an “adventurer,” as someone willing to take risks and act under uncertainty (Cantillon, 1775). Subsequent research, building on Cantillon’s work, defined an entrepreneur as an individual able to recognise and exploit opportunities available to everyone (Kirzner, 1973). Schumpeter defined an entrepreneur as an innovator, involved in “the doing of new things or the doing of things that are already being done in a new way” (Schumpeter, 1947: 151). These various definitions all refer to entrepreneurship as involving recognition of an opportunity and the steps related to transforming the opportunity or idea into a reality. To embark on an entrepreneurial endeavour requires resources and their acquisition has attracted a great deal of research attention in the field of entrepreneurship (see, e.g. Alvarez and Busenitz, 2001; Alvarez and Barney, 2007; Hellmann and Puri, 2002; West and Noel, 2009). Resources are a basic condition for entrepreneurship (Kirzner, 1997; Barney, 1986). Whether tangible or intangible, resources are required for the creation of economic wealth associated to a market opportunity (Barney, 1986; Penrose, 1959). Therefore, lack of the resources required to exploit an opportunity makes access to external sources critical (Alvarez and Barney, 2007; Colombo et al., 2006). Initially, the entrepreneur may have fairly scant knowledge about the environment, lack employees’ commitment and relationships with customers and suppliers (Stinchcombe, 1965). The building of competitive advantage requires an ability to access external sources to overcome these constraints (Dyer and Singh, 1998; Grant and Baden‐Fuller, 2004; Yli‐Renko et al., 2001; Autio et al., 2000; West and Noel, 2009).

Among the most important resources is money. It is well known that one of the main problems faced by entrepreneurs in the early stage of a business initiative, is how to attract external financial investment (see, e.g. Colombo and Grilli, 2010; Hellmann and Puri, 2002; Cosh et al., 2009). Research on entrepreneurial finance examines how entrepreneurs garner the required financial resources and identifies the advantages and disadvantages of different sources of finance at different stages of the new venture’s life cycle. Entrepreneurial finance tends to involve mainly private rather than public funding. This private funding can come from family and friends, incubators and accelerators, crowd funders, business angels, venture capitalists, and banks (Alemany and Andreoli, 2018). These sources may play a broader role in the start-up companies they finance through the provision of business advice, experience, and connections (see, e.g. Hellmann and Puri, 2002; Gilson, 2003; Sapienza et al., 1996; Colombo and Grilli, 2010). Finance, in fact, is not the only resource necessary for start-up success.

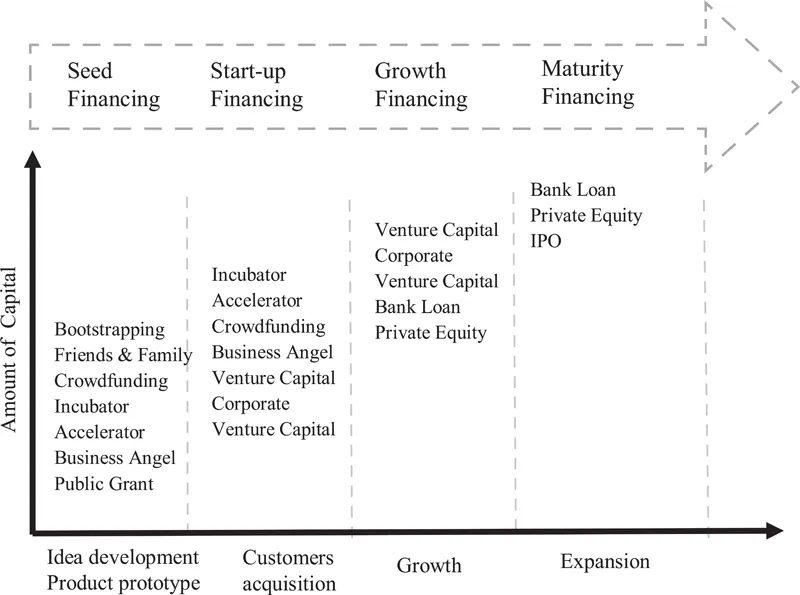

Entrepreneurial finance is relevant both to establish the new company and to support the various stages of development of the entrepreneurial project. Depending on the stage of development, financial and strategic exigencies assume different importance. In this book, we consider four different development stages, which are depicted in Figure 2.1. Figure 2.1 indicates the most typical sources of funding in each stage.1

Seed financing is required in the first phase of the new venture lifecycle. In most cases, this is before the company has been established and refers to identification of a business idea, which the entrepreneur is keen to invest time and resources to its development. This phase may involve the development of a first product or service prototype to test the market and identify who might be willing to pay for ...