- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

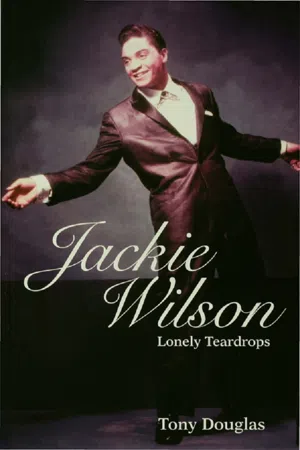

To his many fans, he was known simply as "Mr. Excitement," a singer whose music and stage presence influenced generations of performers, from Elvis Presley to Michael Jackson. Jackie Wilson: Lonely Teardrops looks at the life and career of this deeply troubled artist. Published briefly in a limited edition in the United Kingdom, this Routledge edit

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Jackie Wilson by Tony Douglas in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781136776519Subtopic

Music

Jackie Wilson was far more than a good singer, he was a complete entertainer. He was, as songwriter Jeffrey Perry, who knew him well said, ‘a singers’ singer’. As fellow Detroit singer Betty Lavette related, ‘Many singers achieved stardom through pure good luck, perhaps a timely hit or a pretty face. However, some people seem to be on earth for one purpose only; to express human emotion through song.’ Jackie was one of these people.

JACKIE WILSON, as Jack Leroy Wilson became known, was born at 5.30 a.m. on Saturday, 9 June 1934 at the Herman Kiefer Hospital in Highland Park, Michigan. Jackie was the only surviving son of his black American parents: Jack Wilson, then aged 38, and Eliza Mae Wilson, aged 30. Eliza Mae was born on 22 April 1904, to Bill and Rebecca (nee Cobb) Ranson of Columbus, Mississippi. The Ransons lived on a fair-sized farm on what is known as ‘Cobbs’ Hill’, Motley, just outside Columbus. They were Methodists and gospel singing was a large part of family life – Eliza Mae was a powerful singer, with a large, smiling mouth – and the house shook with foot stomping and singing when the family got together. Jack Wilson Snr, a farmer, was born in 1896, just across the border in Alabama. His mother Anna lived in the nearby town of Starksville, Mississippi. After he married Eliza Mae in 1922, Jack Snr worked for the railroad. They lived for about three years in Columbus before heading to Detroit prior to the Great Depression. Other relatives also made the move ‘up north’ to Michigan, where they settled in Kalamazoo, Muskegon, Pontiac and Detroit. They were helped to find work in the enormous car plants by Jackie’s cousin, Tom Odneal. Many Wilson relatives still live there and carry the names of Taylor, Brown, Gray and Odneal.

Following the move to Detroit came children. Eliza Mae and Jack Snr had had two children previously, but they didn’t survive. Jackie’s birth certificate lists his father as ‘unemployed’ and his mother as a ‘housewife’. While in Detroit, no one can recall Jackie’s father holding down a job. He is best remembered for his drinking: he was a chronic alcoholic who sought the company of similar men. Being the only child of the marriage to survive, Jackie became the apple of Eliza Mae’s eye.

They lived at 1533 Lyman Street, in north-eastern Detroit, a black neighbourhood known as Northend, close to the former Ford foundry plant and the former Chrysler headquarters and assembly plant. The modest little weatherboard house still stands, albeit in a dilapidated state. Jackie was baptised in the nearby Russell Street Baptist church, where he would sing as a child – and where his funeral service would be conducted. To family and close friends Jackie quickly became known as ‘Sonny’.

When Jackie was born in 1934, the world was emerging from the Depression and many people, especially blacks, had headed north to the cities of Chicago, New York, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and Detroit. All sought to better their situation in life through work in the factories and, in the case of Detroit, this generally involved automobile manufacture. Detroit was a meltingpot of social groups and, although not as segregated as in the south, racial barriers prevailed. Blacks and whites mostly lived a separate existence: blacks mainly lived on the east side of Woodward Avenue, rarely the west, and for a member of the black community to become successful by white standards he or she had to have exceptional abilities.

Between the ages of three and ten, Jackie lived with his family on Kenilworth Street in northern Detroit and the first school he attended was Alger Elementary, on Alger Street. His cousin, Virginia Odneal, recalls that Jackie could sing from the age of six: ‘He always said he was going to become a star, and when he became a star and made 25 cents he’d give his mother 15 and keep ten.’ Jackie’s aunt, Rebecca ‘Hot’ Smith, said: ‘Jack was beautiful – he had a God-given voice. He got it from his mother and grandmother; both could sing real good.’

Eliza Mae divorced in 1940, when Jackie was six, and began a common-law relationship with John Lee, a hard worker at the Ford auto plant. John Lee, who was younger than Eliza Mae, was ‘a big, quiet man’ who enjoyed his root cigars and usually owned an impressive car such as a Cadillac. They were, however, never formally married.

Around 1943 Jackie and his family moved a short distance to 248 Cottage Grove, off Woodward Avenue, in Highland Park, an area of three square miles entirely surrounded by the city of Detroit. It was the site of Chrysler Corporation’s international automotive headquarters and the original site of Henry Ford’s first mass-production car plant. Highland Park was a tree-lined working-class neighbourhood of around 35,000 people, with two-storey family homes surrounded by well tended lawns and gardens. To the east was the black neighbourhood, known as the Bowery; to the west the white. The segregation was not clear cut, however. Quite a few black families lived to the west of Woodward without any problems. There were also numerous Arabs, Jews and Italians in the area.

During the same period Jackie befriended Don Hudson and was a constant visitor to his house on Delmar Avenue. Hudson would die at the age of 29 after serving in the Korean War as a 15-year-old and winning the Bronze Star and Purple Heart. He was severely injured, with shrapnel in his head, and was repatriated. He died of a brain seizure around 1963. His sister, Freda, an attractive girl with long hair, was just one year older than Jackie. They soon became sweethearts. ‘He was nine when he told me he was going to marry me,’ said Freda. ‘He told my mother at ten. He’d stay with my brother so he could see me. When he got to ten years old – I thought he was older – he said, “Can I kiss you?” He was like my shining knight, my everything.’

Freda had moved to Detroit with her family from Georgia. Her mother Leathia remarried and the family name became Hood.

When he was little, Jack told me he didn’t want to do nothing else but sing,

recalled Freda.

He said he was going to be an entertainer. That was it; he was not going to do no hard work. We didn’t have no record player, and I don’t think he had no record player at home; he probably listened to the radio. His mother could sing, his father could sing. He’d sing … my goodness. Even in church; he did that on Russell Street, Holbrook, Oakland, all that. They all knew him.

He knew a lot of people who sang – he also used to sing on the corner. In the neighbourhood on the Northend, he’d stand up there in front of the store from about ten or twelve-years-old; he’d say, ‘Hey mama, what you wanna hear, some church songs or some blues?’, or ‘Mama, I’m going to sing you a song, you wanna hear it?’ They’d be giving him money for singing for them. He was just born to sing.

Jackie was always older than his years, in part as a result of his mother’s very liberal upbringing. Freda explained:

When I first knew him, he was ten, singing on the street corner. He’d get this wine; his mother would buy him this Cadillac Club Sweet Red or corn whisky. That’s why I thought he was so old. After you got to know him, he was really very soft – he always acted different. Jack started doing things early [sexually], before most kids even think about it. He was way ahead of himself mentally.

Jackie’s stepfather John (‘Johnny’) Lee worked at the Ford plant for 40 years. By all accounts he and Jackie got along well, although Eliza Mae always put her son’s well-being ahead of John’s. In Freda’s words, ‘She could do anything with his [Johnny’s] money; she liked to play cards. Jack could have anything he wanted.’ A childhood friend of Jackie’s, Eddie Pride, knew his stepfather and mother well.’ He was a very decent, nice man. His mother was a beautiful lady. I couldn’t think of nothing but nice things about her. She was a big help to him – an inspiration.’ Freda remembers that Jackie always had a sense of parental respect, even if deep down he resented an instruction: ‘I don’t care how drunk he got or whatever; he never said nothing to his mother or Johnny. His daddy [Johnny] could be drunk and if his daddy said, “The sky is purple,’ then it was purple!”’

On 15 June 1945, when Jackie was 11, Eliza Mae had her second and only other surviving child, Joyce Ann. Her birthday, six days from Jackie’s, caused some to speculate that their both being Geminis was the reason the relationship later became strained. Nevertheless, Jackie always loved her and would do whatever he could to assist her.

The Lee home didn’t have a record player, but it did have a radio. The singers that Jackie listened to and whom he most admired were Al Jolson, Mario Lanza, the rhythm and blues (R&B) singer Roy Brown, big band baritone Al Hibbler and the gospel great Mahalia Jackson. A common pastime of black families was group singing, especially families who had moved up from the south. Before the days of television, group singing was one of the main forms of home entertainment.

In 1945, Jackie transferred to Thomson Elementary School on Brush Street in Highland Park. (The school has since been torn down and the area has become part of the Chrysler complex.) Jonathan Gallimore, who was two years older than Jackie, captained the Highland Park High School track team. It was the role of the older children to look out for the grade children from the nearby Thomson Elementary School, and Gallimore introduced Jackie to track sports. He remembered Jackie as a fast runner with plenty of track potential: ‘He was a very active little kid, always in trouble,’ he recalls.

No doubt Jackie had gained plenty of running practice eluding the school authorities, for he was an incorrigible truant. The truant officers took their jobs very seriously; they knew Jackie and his close friend, Freddy Pride, by name and these two, along with a few others who had also decided early on that their futures lay in careers as singers, regarded attendance at school as a waste of time. The authorities’ solution to truancy was the Lansing Correctional Institute and, at about the age of 12, Jackie served the first of two detentions there. Despite this, in 1947 Jackie, then aged 13, was enrolled at the respected Highland Park High School; reputed to be one of the best in the nation. At Highland Park High the majority of students were white: of the 400 students who graduated in 1949, 12 were black. Jackie remained uninterested in school.

The Pride family lived in west Highland Park, a predominantly white section. Eddie Pride, who also attended Jackie’s school, comments: ‘Highland Park was an excellent school; I was really proud. Highland Park at that time went up to the fourteenth grade. That way they got to give the kids a chance to do two years of college – free.’ Regarding racism, Eddie says, ‘You know, I didn’t know nothing about no race shit until I got in the army. Everybody in the class was white. We used to have to go through the whole school looking for somebody black. We didn’t get too involved in that race thing. My neighbours were white, and all the people on my paper route were white. I just happened to be black.’

Freddy Pride, twin brother of Eddie and now deceased, was one of Jackie’s closest friends as well as being a fine singer. Freddy, who was two years older than Jack, became one of the original Midnighters group. Jackie was a regular and welcome visitor to the Pride home, where they met to practise their singing. Eddie said:

I knew Jack since high school. He lived fast; even at 15 he was singing at clubs. He was quite fabulous, even then, as a youngster. Way ahead of himself. Jack sang ‘Danny Boy’ when he was in high school. I said, ‘Man, that’d be a hell of a recording.’ He could sing opera. At that time Mario Lanza was out and Jack imitated him a lot. Jack didn’t hardly go to school at all, but he would come down for music and excelled at music. His mother had him in church; had him in the choir. She had a voice, too. She taught Jack all the things, falsetto, and all that stuff he could do. He was doing that at 13, 14, 15 years old.

The school Glee Club also met at the Pride house and was under the tutelage of an elderly woman, Mrs Kent. Eddie Pride’s sister, Alice, a year younger than Jackie, was also a member of the Glee Club, which she recalls had about 15 members. ‘She’d always tell him he was going to make it,’ said Alice. ‘The song she liked was “Silent Night” and she told everybody, “Everybody be quiet! Jack! Come up here. I want you to sing. Jack, you’re going to be good.” She praised him so. We would be laughing. He was about 15 then. She discovered him. She’d say, “You’re going to make it, you have the voice.” He could hit those high notes, even back then.’

Jackie spent much of his time at Northern High, Freda’s school. ‘He would go into Highland Park High School and straight out the back door,’ stated Freda. ‘He spent more time over at my school than he did at his. We’d be looking out the window at him; he’d be standing outside messing with the girls. I’d know to go to that window in the study hall and wait …’ Jackie was a womaniser from an early age, and was usually to be found wherever there were girls.

Martha Scott, who was at school with Jackie and became Highland Park’s mayor, always knew he was going to be a star. Once a month a student would sing at school assembly. She remembers how nobody would miss morning assembly on the days Jackie sang. In 1949, Jackie’s teacher prophetically remarked on his report card: ‘Jack’s story is a sad one. He has a voice out of this world, but can’t get to school on time to do anything about it. He has talent without ambition and charm without responsibility. I have doubts as to his future in 9-B or in life.’ Jackie went only as far as the ninth grade, dropping out in 1950 when he was 16. His ambitions lay outside anything he could learn in school and he loathed discipline. Ernestine Smith, a few years older and a near neighbour, stated, ‘I think he dropped out early and did all the things my dad said he was going to do; drink and get girls pregnant.’ Martha Scott recalls, amazingly, that Jackie had impregnated around 15 girls before he left school. Freda also confirmed this.

Another Highland Park student, Loretta Deloach, was a friend of Jackie’s and the Pride family, living in their apartment building. ‘He always had this lovely voice. He would always sing when somebody asked him to sing for church or school; or if the kids wanted to raise some money for a program we’d have these talent shows and we’d ask him to sing, and he always would sing for us. A delightful young man; not conceited like some.

‘We had this Sanders candy store and bakery [nearby] and the guys would go there and kinda get this candy without paying for it. We girls would try to make ourselves look attractive so the guys would give us some candy. Jack he always held out, but he’d give you more than the other guys. He’d give you a pound of candy. He was outgoing and everyone accepted him. As a youngster he was still good looking. The women were after him.’ Loretta recalls that after Jackie became famous he was still the same warm person, ‘He didn’t forget his friends. He’d always come back to Highland Park. When he came back, it was a big deal.’

Detroit during that period was a boom town. Roquel ‘Billy’ Davis was a close friend and neighbour of Jackie’s and became one of his songwriters, co-writing most of his major hits. He recalls: ‘In Highland Park in those days there was a sense of community. Everyone looked out for one another; it was like a big family. We played together, we entertained together, we ate together, we shared everything together. Poor little rich kids; that’s what I called us.’

At around the age of 12, Jackie formed a small group he called ‘The Ever Ready Gospel Singers’. Naturally, he sang lead. Jackie’s best friend throughout most of his life was a lanky fellow with a big jaw and a friendly smile, Johnny Jones. ‘JJ’, as he was generally known, was three years Jackie’s senior and lived nearby. They often spent the night at each other’s homes and attended the same Russell Street Baptist Church. JJ was part of the gospel group and sang bass. Two brothers, Emmanuel and Lorenzo, made up the quartet.

Jack was the group,

according to Freda.

They performed at all kinds of churches throughout the day. A collection would be taken for them – a quarter at least. They could tear up a church! In the evening, after church, they’d shoot craps and he’d win all their money. Those people believed they were giving to God; these were children of God. They didn’t know Jack was shooting craps. Jack was just smart from the street. He always knew what notes he could reach. He did his own stuff; nobody trained him, they didn’t have to.’ They sang the church circuit around the Northend area of Detroit, remaining active until he was 15 or 16.

Jonathan Gallimore recalls, ‘They formed a group and used to sing on all the corners: the corner of Oakland and Connecticut, then they was around the west side and on the playground at the Highland Park High School and at Northern High School and the Community Centre.’

Ernestine Smith lived on Russell Street, close to where Jackie lived. Ernestine’s father was strict, religious and hardworking. He discouraged Ernestine from any involvement with Jackie or his friends. The back porch of the Smith house looked out on the alley where Jackie and his group often hung out. It was also the place where his father gathered with his ‘wino’ cronies.

Jack was basically a good young man,

said Ernestine.

He liked to drink that wine, though. My dad picked who I mixed with. For some reason he didn’t like me to mix too much with Jack. He was good looking; I always admired him and liked him, but had a little fear in my heart because he could be a little demanding: ‘Come here!’, like that. The way he’d talk to you! ‘When I tell you to come over here, I mean it!’ He said, ‘I like you. Do you wanna be my girl’ I said, ‘No, no.’ I figured he was younger than me. One night he was with the fellas and he called me. I ran, I beat O.J. [Simpson] running.

My daddy said, ‘He’s out there in the world, he’s rough.’ That’s the way he grew up and survived. In winter they’d put on a heavy coat and gloves. Some had holes in the gloves, mittens. If it was cold, that wine would heat them up. There was a Standard gas station in the alley. He liked to shoot dice with the guys. Jack would come up the alley to be with his dad and those men. There was a store nearby where they’d buy their liquor. They’d drink and solve the world’s problems. There’d be six, seven or eight men. But if the minister came down the street, they had respect for him.

They’d buy the wine and pass the bottle; they’d be laughing. If Jack would come up, they’d sing. They seemed always to be having fun. My dad resented that; he worked hard and thought they should. He’d say, ‘Get away from my porch.’ They would get carried away and be cussing. Jack did have a split life. I had seen him in church and saw him sing, but he could cuss! My dad was a churchgoer and didn’t like the cussing. They’d say, ‘Here comes that man, he’s going to give us a sermon.’ Th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Why a Book on Jackie Wilson

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Danny Boy

- Chapter Two: You Can’t Keep a Good Man Down

- Chapter Three: Reet Petite

- Chapter Four: You’d Better Know It

- Chapter Five: A Woman. a Lover. a Friend

- Chapter Six: I’m Wanderin’

- Chapter Seven: Higher and Higher

- Chapter Eight: A Kiss, a Thrill and Goodbye

- Chapter Nine: Soul Galore

- Chapter Ten: I Don’t Need You Around

- Chapter Eleven: Those Heartaches

- Chapter Twelve: This Love Is Real

- Chapter Thirteen: Beautiful Day

- Chapter Fourteen: It’s All Over

- Chapter Fifteen: Your Loss. My Gain

- Chapter Sixteen: The Greatest Hurt

- Chapter Seventeen: Postscript

- Bibliography

- Discography