![]()

01

THE STADIUM AS A BUILDING TYPE

1.1 | A VENUE FOR WATCHING SPORT |

1.2 | HISTORY |

1.3 | CURRENT REQUIREMENTS |

1.1 A VENUE FOR WATCHING SPORT A VENUE FOR WATCHING SPORT

1.1.1 ARCHITECTURAL QUALITY A VENUE FOR WATCHING SPORT

A sports stadium can be seen as a huge theatre for the exhibition of heroic feats. It is this combination of dramatic function and monumental scale that leads to powerful civic architecture.

The first great prototype, the Colosseum of Ancient Rome, did indeed achieve this ideal, but unfortunately very few stadia since then have succeeded as well. The worst are rather brutal, uncomfortable places, casting a spell of depression on their surroundings for the long periods when they stand empty and unused, in sharp contrast to the short periods of extreme congestion on event days. However the best are comfortable, safe and inspiring; they offer their patrons an enjoyable afternoon’s or evening’s entertainment. Few, however, achieve a level of architectural excellence.

Blending the tiers of seating, the ramps or stairs, and the immense roof structures into a single harmonious and engaging architectural ideal is a challenge that sometimes seems almost beyond solution. The result is that sports stadia tend to be lumpy agglomerations of elements that are out of scale with their surroundings and in conflict with each other, and often harshly detailed and finished.

This book cannot show the reader how to create great architecture. But by clarifying the technical requirements as much as possible, and by showing how these problems have been solved in particular cases, it hopes at least to help designers with difficult briefs to create fine buildings. If this process is done well, the rewards are great.

1.1.2 FINANCIAL VIABILITY

In the 1950s, when watching live sport was already a major pastime for millions, sports grounds around the Western world were filled to bursting point at every match. But in the decades following this post-World War II boom, those same venues struggled to attract large audiences and many were fighting for financial survival. Fortunately, owners and managers have been creative in finding solutions. There are now clear signs at the beginning of the 21st century that audiences are returning to traditional sports, and new events are helping to fill stadia beyond their previous event schedule.

Heinz Field in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, home of the Pittsburgh Steelers NFL team. Architects: Populous

The reality is that, for a sports stadium to be financially viable, some form of subsidy is still often required, whether open or covert. With this in mind, there are usually three factors at play:

• Other revenue streams for the stadium should ensure the subsidy is not impossibly large.

• The project should be sufficiently attractive to justify investment from the public purse.

• It should be sufficiently attractive to private sponsors.

Some may feel that the above statements are too pessimistic. Consider the North American experience, however. The USA and Canada have highly affluent populations, totalling around 350 million. They are keen on sport and have energetic leisure entrepreneurs and managers very skilled at extracting the customer’s dollar. Of all the world’s countries, the USA and Canada should be able to make their stadia pay. They have seemingly explored every avenue – huge seating capacities, multi-use functions, adaptable seating configurations, total enclosure to ensure comfort, retractable roofing to protect from the elements – and yet they still struggle to make a profit, particularly when the huge initial costs of development are taken into account.

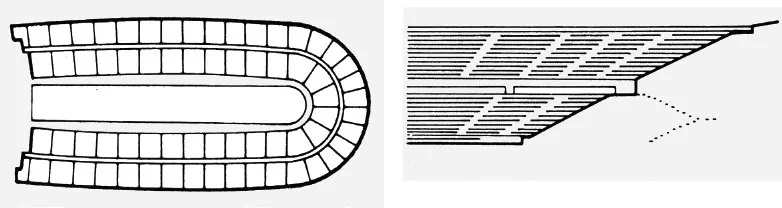

Figure 1.1

The U-shaped sunken stadium at Athens, first built in 331 bc for the staging of foot races, was restored and used for the first modern Olympics In 1896.

Just as there are no hard and fast rules for producing great architecture, there are no magic formulae to guarantee profitable stadia. Teams of experts must analyse the costs and potential revenues for each individual case and find a viable solution; or, at least, leave a gap that can be bridged by private sponsors or public support.

This book identifies the factors that need to be considered. But before getting into such technical details, we should make the most important point of all: sports and entertainment venues are one of the great historic building types, representing some of the very earliest works of architecture (Ancient Greek stadia), some of the most pivotal (Roman amphitheatres and thermae), and some of the most beautiful (from the Colosseum in Ancient Rome to the Olympic Park in Munich 20 centuries later). Therefore we will start with a brief historic survey.

1.2 HISTORY

1.2.1 ANCIENT GREECE

The ancestral prototypes for modern sports facilities of all kinds are the stadia and hippodromes of Ancient Greece. Here, Olympic and other sporting contests were staged, starting – as far as we can tell – in the eighth century bc.

STADIA

Greek stadia (foot racecourses) were laid out in a U-shape, with the straight end forming the starting line. These stadia varied somewhat in length, the one at Delphi just under 183m long, the one at Olympia about 192m. Such stadia were built in all cities where games were played. Some, following the pattern of Greek theatres, were cut out of a hillside so that banks of seats with good sightlines could be formed naturally, while others were constructed on flat ground. In the latter case the performance area was sometimes slightly excavated to allow for the formation of shallow seating tiers along the sides.

Stadia built on the flat existed at Ephesus, Athens and Delphi. The latter – almost 183m long and 28m wide – had a shallow bank of seats along one side and around the curved end. The judges’ seats were at the midpoint of the long side, very much like a modern facility. The stadium at Athens was first built in 331 bc, reconstructed in ad 160 and reconstructed again in 1896 for the first modern Olympic Games. In its latest form it can still be seen accommodating up to 50,000 people in 46 rows (Figure 1.1).

Hillside stadia existed at Olympia, Thebes and Epidauros, and their similarity to Ancient Greek theatres is unmistakable: these are essentially elongated theatres for the staging of spectacular physical feats. From them runs a direct line of development, firstly to the multi-tiered Roman amphitheatres, and ultimately to modern-day sports stadia.

The civic importance of such sporting facilities in Ancient Greek life is demonstrated particularly well at Olympia, on the island of Peloponnesus. The site housed a great complex of temples and altars to various deities and, at the height of its development, was a rendezvous for many across Ancient Greece. There was a sports field situated adjacent to an enclosed training gymnasium, and along the edge of the field, a colonnade with stone steps to accommodate the spectators. As the track became more popular, two stands were constructed, facing each other on opposite sides of the activity area. The fully developed stadium consisted of a track 192m long and 32m wide with rising tiers of seats on massive sloping earth banks along the sides. These seats ultimately accommodated up to 45,000 spectators. The stadium had two entrances, the Pompic and the Secret, the latter used only by the judges.

Adjacent to the stadium at Olympia was a much longer hippodrome for horse and chariot races, and in these twin facilities one clearly discerns the embryonic forms of modern athletic stadia and racing circuits. The stadium has been excavated and restored and can be studied, but the hippodrome has not survived.

While modern, large-capacity, roofed stadia can seldom have the simple forms used in Ancient Greece, there are occasions when the quiet repose of these beautiful antecedents can be emulated by modern architects. Unobtrusive form is important, as is the use of natural materials which blend closely with the surroundings so that it is difficult to say where landscape ends and building begins.

HIPPODROMES

These courses for horse and chariot races were between 198m and 228m long, and 37m wide. They were also laid out in a U-shape. Like Ancient Greek theatres, hippodromes were usually made on the slope of a hill to give rising tiers of seating. From them developed the later Roman circuses, although these were more elongated and much narrower.

1.2.2 ROMAN AMPHITHEATRES

The militaristic Romans were more interested in public displays of mortal combat than in races and athletic events, and to accommodate this spectacle they developed a new amphitheatrical form: an elliptical arena surrounded on all sides by high-rising tiers of seats enabling the maximum number of spectators to have a clear view of the terrible events staged before them. The word arena is derived from the Latin word for sand, or sandy land, referring to the layer of sand that was spread on the activity area to absorb spilled blood.

The overall form was, in effect, two Ancient Greek theatres joined together to form a complete ellipse. But the size of the later Roman amphitheatres ruled out any reliance on natural ground slopes to provide the necessary seating profile. Therefore the Romans began to construct artificial slopes around the central arena – first in timber (these obviously have not survived) and, starting in the first century ad, in stone and an early form of concrete. Magnificent examples of the latter may still be seen in Arles and Nimes (stone), and in Rome, Verona and Pula (stone and a form of concrete). The amphitheatre at Arles, constructed in around 46 bc, accommodated 21,000 spectators in three storeys. Despite considerable damage in the intervening centuries – the third storey which held the posts supporting a tented roof has gone – it has been used recently for bullfighting. The Nimes amphitheatre, dating from the second century ad, is smaller but in excellent condition and also in regular use. The great amphitheatre in Verona, built in about 100 ad, is world famous as a venue for opera performances. Originally it measured 152m by 123m overall, but very little remains of the outer aisle. It currently seats about 22,000 people and measures 73m by 44m.

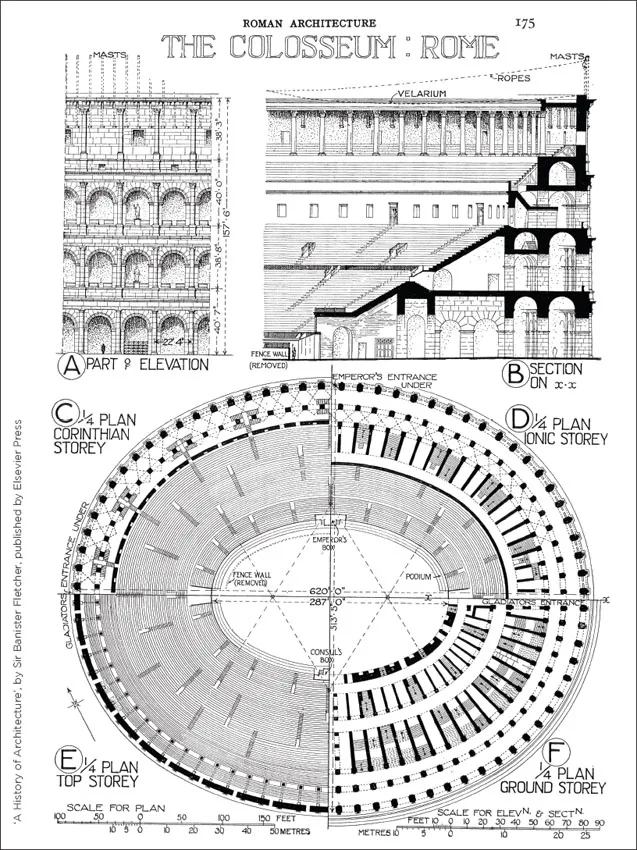

Figure 1.2

The Colosseum of Rome (ad 82) was built for gladiatorial combat and not for races. It therefore took the form of a theatre in which rising tiers of seats, forming an artificial hillside, completely surrounded an area. The great stone and concrete drum fused engineering, theatre and art more successfully than most modern stadia.

The Flavian Amphitheatre, in Rome (Figure 1.2), better known as the Colosseum from the eighth century onwards, is the greatest exemplar of this building type and has seldom been surpassed to this day as a rational fusion of engineering, theatre and art. Construction began in ad 70 and finished 12 years later. The structure formed a giant ellipse of 189m by 155m and rose to a height of four storeys, accommodating 48,000 people. It was a stadium capacity that would not be exceeded until the 20th century. Spectators had good sightlines to the arena below, the latter being an ellipse of roughly 88m by 55m, bounded by a 4.6m-high wall. There were 80 arched openings to each of the lower three storeys, with engaged columns and encircling entablatures applied to the outer wall surface as ornamentation. The openings at ground level gave entrance to the tiers of seats. The structural cross-section (Figure 1.2B), broadening from the top down to the base, solved three problems at one stroke:

• It formed an artificial hillside, giving spectators a theatrical view of the action.

• It formed a stable structure. The tiers of seats were supported on a complex series of barrel-vaults and arches which distributed the immense loads via an ever-widening structure down to foundation level.

• The volume of internal space suited the numbers of people circulating at each level – fewest at the top, most at the base. The internal aisles and access passages formed by the structural arcades were so well-planned that the entire amphitheatre could, it is thought, have been evacuated in a matter of minutes.

The arena was used for gladiatorial contests and other entertainments. It could be flooded with water for naval and aquatic displays. Beneath the arena was a warren of chambers and passageways to accommodate performers, gl...