![]()

1

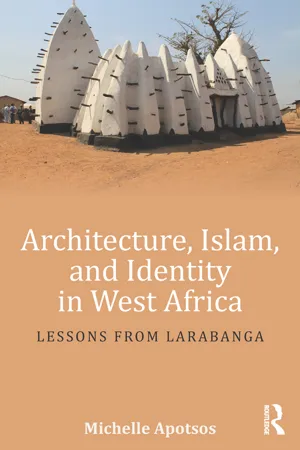

LOCATING LARABANGA

Architecture and Contemporary Islamic Identity in West Africa

Afro-Islamic Architecture in Context: Definitions, Approaches, and Assessments

Islam as a dedicated, cohesive religion and cultural way of life has thrived across numerous contexts within the West African region. In Ghana specifically, Islam has continued to create culturally and spiritually compelling narratives that have endured and even flourished within the contemporary period, in areas ranging from rural communities like Larabanga to the larger urban capitals of Accra, Tamale, and Wa. Importantly, these developments have occurred despite the various political disruptions and social tensions with which Islam has increasingly become associated, and one reason for Islam’s continued success is its strategic use of space and the built environment, as apparatuses that individuals have used across religious, cultural, and social contexts to organize physical environments and craft lived reality.

In contexts such as Larabanga, architecture acts as a symbolic representation of ideals and traditions that have informed the specific cultural realities of the community, as well as a platform for engagement with incoming global influences. These conversations are encoded variously into the physical and spatial organization of the village as new registers of knowledge that create a palimpsest of history, identity, and reality, each colliding and negotiating with each other in different ways. As such, architecture stands as the articulation of the fluid and occasionally unexpected trajectories that Larabanga, along with many other contemporary Afro-Islamic communities, have taken as they struggle to bridge the gaps between established cultural identities and modern realities. But in order to understand how one can think through the reality of built form as it exists within these contexts, it is important to flesh out the modes through which architecture as a concept is capable of manifesting itself within the parameters provided by individual contexts of Wesst African Islamic communities.

The variety of Afro-Islamic architectural types that exist across North and West Africa provide important insights for understanding how the built environment in Larabanga has come to function as both a product and a producer of cultural reality. From the ksour of southern Morocco to the mosques of northern Ghana, this diversity of Afro-Islamic architectural form reveals the presence of highly specialized structural solutions that have been designed to address the problems of living within distinctive socio-political, cultural, spiritual, and climatic environments. In fact, the diversity is such that occasionally these forms push against many of the conceptual boundaries that have come to define “architecture” in its most basic sense as a three-dimensional shelter. The massive earthen mosques of the Niger Bend region in Mali, such as those in Djenné and proximate communities, blur the boundaries between structural form and sculptural object through their highly fluid, hand-modeled aesthetic. Specifically, they employ a building style whose form evokes distinctly haptic and optic senses through sensual combinations of protrusion and recession, form and void, all of which collectively create movement, visual interest, and dynamism through their dramatic manipulation of light and dark. Such structures literally manifest Bruno Zevi’s classification of architecture as “a great hollowed-out sculpture which man enters and apprehends by moving about within it.”1 These forms also deemphasize the functional, traditionally “architectural” aspects that lie beneath these molded surfaces. Even the nuts and bolts of these spaces are capable of becoming part of aesthetic discourse. Locks, windows, doors, and even ladders have developed artistic identities of their own when they are displaced from their original contexts and reimagined as autonomous aesthetic objects within the institutionalized settings of Western museums.2

Towards challenging traditional notions of architecture even further, many of these forms also problematize two specific hegemonic qualities assumed to be essential to the architectural condition, namely permanence and presence. These two qualities require extensive reconsideration in the context of Afro-Islamic building practice. Permanence, as it is often thought of in European and American contexts, refers to “object-permanence,” or the lasting aspect of a conventional architectural sign that preserves the signifier in a way that verbal and other forms of abstract communication cannot.3 Cultural philosopher Walter Benjamin once considered this type of permanence an “Ur-phenomenon,” “vital as a material “witness” because it resists easy erasure and remains within the city as a reminder.”4 However, many populations in Islamic Africa are engaged in a continuous response to changing climate conditions, shifting kinship organizations, population migrations, military conflicts, and modernization, conversations that first and foremost emerge within the physical environment. These dynamic conditions require an equally dynamic built environment, one in tune with the current moment of the community and able to respond accordingly and occasionally with improvisation. As such, “permanence” in Afro-Islamic communities is often translated in the structural environment in ways relating to process rather than product. The tent structures of many North and West African nomadic peoples are natural examples of this conceptual disconnect. Most Western scholars would consider these structures inherently impermanent because of their fundamentally transient reality. However, the tenacity of these nomadic architectural traditions, the symbolism of their structural components, the formal consistency of their construction and deconstruction, and the continuity of their functional and social roles in nomadic society all position the tent itself as a permanent structure in both process and practice, much more so than many other “modern” Western forms whose life cycle may end after a few years.

Materials also play a role in interpretations of permanence in historical African architectural forms. Structures such as the aforementioned Sahelian earth and timber mosques require regular upkeep from specialized local mason guilds and the broader community in order to withstand the stresses of time and the environment. As such, both permanence and presence are encoded within such structures not through their physical qualities or existence, but through the development of the complex communal social maintenance systems. The yearly replastering “festivals” that often accompany this maintenance reflect a continuity of ideology, tradition, and social cohesion within the communal sphere. Along these lines, there are also some areas in which the concepts of permanence and presence overlap. “Structures” such as rock-outlined desert mosques present in multiple Islamic contexts can hardly be said to be “present,” much less permanent in a normative sense (see Figure 1.1).5 They are composed of informal spaces demarcated from their surroundings by a simple outline of rocks placed on the ground. Yet both permanence and presence are encoded within these forms through the very durability of Islamic prayer protocols that require an architectural presence consistently located in time and space within a potentially featureless landscape. Lastly, there exist architectural forms that are even less direct and in fact stand as more of a “second order” space. These spaces encompass the involuntary traces, remnants, and material leavings of actions and performances left behind that provide symbolic evidence of past site-based events. Just as rocks outlining a mosque are conscious, declarative structural statements of presence, ashes from a past fire, collections of feathers and bones in an open area, and even trampled grass are the unspoken testimonials of a previously inhabited space. A specialized cultural knowledge is required to read and subsequently translate such a site as a place of action and habitation, whether it is ceremonial, ritual, or recreational. It is only by appropriately interpreting this possibly unintended, unconscious, or oblivious detritus that makes the identification of space possible and underscores the fact that almost every space contains components of its function, meaning, or existence. These accidental symbols indicate both the presence and definition of a space at a particular moment in time; such constructions allow many spaces to elide the form-to-function essentialism that often accompanies structural genres in other contexts. Through these examples, both permanence and presence are shown to exist within different Afro-Islamic spaces. Yet they are informed by decidedly different frameworks of interpretation that privilege the diversity of the environment in which they appear, whose political, social, and cultural conditions require specific “architectural” constructs to organize the landscape in ways commensurate with the requirements of its population.

FIGURE 1.1 Rock mosque, Larabanga, Ghana, 2011.

How then can we connect these forms along a definable continuum with regards to Afro-Islamic architectural identity? Space becomes an extremely important element at the most basic level within manifestations of architectural form, which we will define as an object that makes a space “present” through demarcation. Whether one is looking at the coral walls of a Swahili house or the rock outlines of a desert mosque, at the heart of the architectural experience is a sense of “thereness,” a quality that allows an individual to recognize the occurrence of a specific space based on evidence as clear as discernible markers, or as vague as specialized knowledge. Because of its role in making space “present,” architectural form is very important in the context of Afro-Islamic spatial analysis, and is one of the primary methods through which the human environment communicates in such contexts.

Within this rubric, another important quality of Afro-Islamic architectural form is that it has a number of different realities, each dictated by a Muslim sensibility. Human beings are simultaneously immersed in a cluster of social, cultural, and spiritual identities that subsequently manifest in the hybridization of various architectural identities as well, whether it is the physical space of a domicile located within a communal space, or the conceptual space created by ethnicity, gender, or class that dictates one’s movements, interactions with, and ability to access a site. In each case, an individual’s relationship with these areas establishes layers of identity that compose that person’s reality. Moreover, these spaces can overlap, as when individuals organize domestic and communal areas according to socio-cultural norms, ranks, and hierarchies within familial or communal frameworks.6

Manifestations of space are made equally interactive and multidimensional through one’s awareness of and response to them. Such reactions are defined by the presence and experience of borders, boundaries, and peripheries established via tangible modes such as walls and ceilings, as well as more indirect devices such as visual symbols, objects, or bodies of esoteric knowledge. These boundaries divide, mix, and isolate bodies in space, but they also differentiate “in” from “out,” center from periphery, and membership from exclusion. In doing so, boundaries make place a purposeful, motivated area by containing, enhancing, and providing avenues of action for “bodies in space doing purposeful things.”7

Yet boundaries also do something very important, something that at first glance appears to be a contradiction to its tendency to separate and divide. Boundaries and borders also maintain penetration points, or areas of permeability, in the form of entrances and exits that enable movement from one realm to another. Scholars have long understood that such thresholds are required for a built space to truly become an “architectural” space, but the importance of their role in Afro-Islamic space cannot be underemphasized. These transformative openings maintain a particular brand of power as meeting points between the public and private, the foreign and the familiar, and the unknown and the known within Islamic contexts in Africa. These spaces are often interpreted as highly charged, generative areas that enable physical and symbolical transitions from one “world” into another.8 The power of these passages as channels from interior to exterior charges these structural areas with a great deal of authoritative aura, a concept developed in other types of non-Islamic media such as the Kongolese Nkisi figure, whose architectonic body houses forces evoked by the presence of spiritually efficacious materials (see Figure 1.2). The forces of the Nkisi are discharged through the piercing of its bodily envelope, a penetrative occurrence that activates the power of the figure by providing a channel of access to the outside world, subsequently creating a threshold between inner and outer realms.

The potency of this threshold in architectural objects is obviously not specific to just Afro-Islamic architectural traditions. Numerous historical and contemporary architectural habitats around the world continue to deploy similar conceptual (and decorative) emphases on the entrance points of built forms, particularly religious architectures which seem particularly preoccupied with the type of agency that points of penetration can evoke towards manipulating subsequent experiences of the interior space. The entrance façades of Romanesque churches in medieval France, for example, received an inordinate amount of decorative attention towards optimizing the religious learning experience of congregants who would come to worship. This decoration also transformed these entrances into spiritual portals that actively burdened incoming worshippers with the weighty visual narratives of well-known religious parables, explicit...