Handbook of Drying of Vegetables and Vegetable Products

- 538 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Handbook of Drying of Vegetables and Vegetable Products

About this book

This handbook provides a comprehensive overview of the processes and technologies in drying of vegetables and vegetable products. The Handbook of Drying of Vegetables and Vegetable Products discusses various technologies such as hot airflow drying, freeze drying, solar drying, microwave drying, radio frequency drying, infrared radiation drying, ultrasound assisted drying, and smart drying. The book's chapters are clustered around major themes including drying processes and technologies, drying of specific vegetable products, properties during vegetable drying, and modeling, measurements, packaging & safety.

Specifically, the book covers drying of different parts and types of vegetables such as mushrooms and herbs; changes to the properties of pigments, nutrients, and texture during drying process; dried products storage; nondestructive measurement and monitoring of moisture and morphological changes during vegetable drying; novel packaging; and computational fluid dynamics.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Section IV

Others (Modeling, Measurements, Packaging, and Safety of Dried Vegetables and Vegetable Products)

15 Vegetable Dryer Modeling

CONTENTS

- 15.1 Introduction

- 15.1.1 Vegetables

- 15.1.2 Vegetable Preservation

- 15.1.3 Properties of Air

- 15.1.3.1 Absolute Humidity

- 15.1.3.2 Relative Humidity

- 15.1.3.3 Density

- 15.1.3.4 Enthalpy

- 15.2 Thin-Layer Drying Curves

- 15.2.1 Important Regions in the Drying Curve

- 15.2.2 Falling Rate Period

- 15.2.3 Summary of Drying Rates

- 15.2.4 Pressure Drop

- 15.2.5 Residence Time

- 15.2.6 Effects of Main Parameters on Drying Kinetics

- 15.2.6.1 Air Temperature

- 15.2.6.2 Air Relative Humidity

- 15.2.6.3 Air Speed

- 15.2.6.4 Product Composition

- 15.2.6.5 Product Surface

- 15.2.6.6 Product Thickness

- 15.3 Theoretical Predictions of Drying Behavior of Vegetables

- 15.3.1 Empirical Models of Product Drying

- 15.3.2 Modeling Drying at Surface

- 15.3.3 Modeling Drying within Product

- 15.3.4 Constant vs. Changing Conditions

- 15.3.4.1 Two-Layer Model

- 15.3.5 Finite Element/Finite Difference Models

- 15.3.5.1 Finite Difference Method

- 15.3.5.2 Finite Element Methods

- 15.3.5.3 Summary of Modeling Methods

- 15.4 Modeling of Specific Dryers

- 15.4.1 Modeling of Dryers

- 15.4.1.1 The Main Equations

- 15.4.1.2 Direction of Air Flow

- 15.4.1.3 Batch Dryer or Continuous Dryer?

- 15.4.1.4 Type of Product Used?

- 15.4.2 Hot Air Drying

- 15.4.2.1 Kiln Dryer

- 15.4.2.2 Tray Dryer

- 15.4.2.3 Tunnel Dryers

- 15.4.2.4 Belt Dryers

- 15.4.3 Solar Dryers

- 15.4.4 Fluidized Bed Dryers

- 15.4.5 Heat Pump Dryers

- 15.4.6 Spray Dryers

- 15.4.7 Sublimation Drying

- 15.5 Conclusions

- References

15.1 INTRODUCTION

15.1.1 VEGETABLES

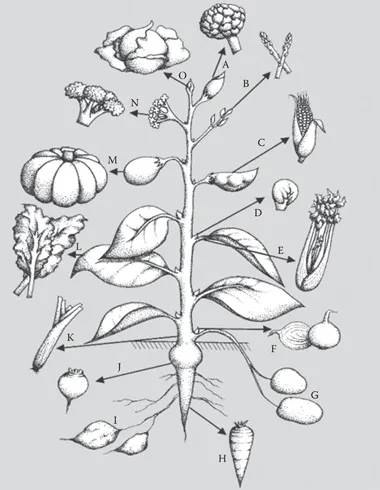

- The seeds are small embryonic plants, usually with some stored food.

- Formation of seed starts with pollination of the flower. The embryo is developed from the zygote and the seed coat from the integuments of the ovule.

- After fertilization, the endosperm becomes the food.

- Plant seeds used for food include rice, legume seeds (peanuts, peas, and beans), corn, and coconut.

- Some seeds are consumed immature such as sweet corn and peas. Beans and peas (snow peas) are usually eaten when seed pods are fleshy.

- The major function of roots is to anchor or support the aerial parts of the plant and to absorb water and inorganic nutrients from the soil.

- In many plant species the tap root functions as a vegetative reproductive organ that can maintain the species through winter or dry conditions until favorable growing conditions returns. These roots store large amounts of carbohydrates and usually have low rates of respiration. Typical examples are carrots and radishes (H). Sweet potatoes are swollen and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Editors

- Contributors

- Section I Drying Processes and Technologies

- Section II Drying of Specific Vegetable Products

- Section III Changes in Properties during Vegetable Drying

- Section IV Others (Modeling, Measurements, Packaging, and Safety of Dried Vegetables and Vegetable Products)

- Index