- 122 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

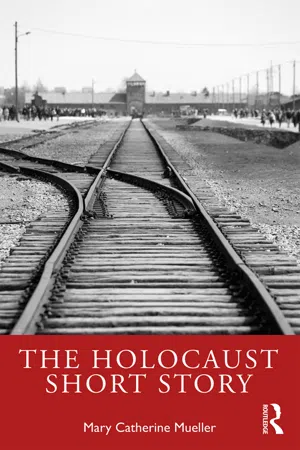

The Holocaust Short Story

About this book

The Holocaust Short Story is the only book devoted entirely to representations of the Holocaust in the short story genre. The book highlights how the explosiveness of the moment captured in each short story is more immediate and more intense, and therefore recreates horrifying emotional reactions for the reader. The main themes confronted in the book deal with the collapse of human relationships, the collapse of the home, and the dying of time in the monotony and angst of surrounding death chambers. The book thoroughly introduces the genres of both the short story and Holocaust writing, explaining the key features and theories in the area. Each chapter then looks at the stories in detail, including work by Ida Fink, Tadeusz Borowski, Rokhl Korn, Frume Halpern, and Cynthia Ozick. This book is essential reading for anyone working on Holocaust literature, trauma studies, Jewish studies, Jewish literature, and the short story genre.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

The collapse of time

Introduction to select themes of the Holocaust short story

All of us walk around naked. The delousing is finally over, and our striped suits are back from the tanks of Cyclone B solution, an efficient killer of lice in clothing and of men in gas chambers.– Tadeusz Borowski, “This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen”

In The Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Immanuel Kant rejected the Newtonian theory of absolute, objective time (because it could not possibly be experienced) and maintained that time was a subjective form or foundation of all experience. But even though it was subjective, it was also universal – the same for everybody.2

With the special theory of relativity in 1905 Einstein calculated how time in one reference system moving away at a constant velocity appears to slow down when viewed from another system at rest relative to it, and in his general theory of relativity of 1916 he extended the theory to that of the time change of accelerated bodies. Since every bit of matter in the universe generates a gravitational force and since gravity is equivalent to acceleration, he concluded that “every reference body has its own particular time.”3

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The features of the Holocaust short story

- 1 The collapse of time: Introduction to select themes of the Holocaust short story

- 2 The collapse of silence: The role of silence in Ida Fink’s short stories

- 3 The collapse of man – and then man created the anti-man: The role of the Muselman figure in select short stories from Tadeusz Borowski’s This Way for the Gas, Ladies And Gentlemen

- 4 The collapse of relationships and home: The Nazi assault on relationships, family, and home as portrayed in two Yiddish Holocaust short stories

- 5 The collapse of motherhood: Cynthia Ozick’s short story “The Shawl”

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index