- 158 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Creative Play with Children at Risk

About this book

This second edition is fully updated with the latest good practice in play. Based on an understanding of 'Neuro-Dramatic-Play', the book shows that play is an essential part of children's healthy development and many children 'at risk' are those who are unable to play. It includes work with children with learning difficulties as well as those with developmental delay.

The book includes current thinking on neuroscience and illustrates the importance of mindfulness in our work with children.

Topics include:

- creating the safe space

- understanding and working with fear

- understanding and working with anger and rage

- new stories and worksheets

- cross cultural understanding of play

- dressing-up and enactment

- masks and puppets

The book is written for teachers, parents and therapists, and all those who seek to enhance the lives of children.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Creative Play with Children at Risk by Sue Jennings in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Clinical Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Practical play and drama

Neuro-Dramatic-Play and Embodiment-Projection-Role in practice

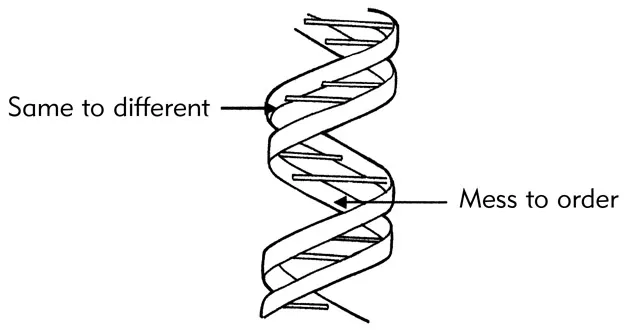

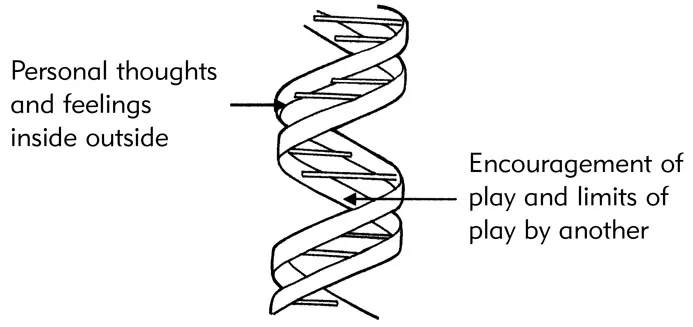

The practical ideas for play and drama in this book are underpinned by contemporary theory drawn from neuroscience and play and dramatherapy. The particular focus is on Neuro-Dramatic-Play (NDP) and Embodiment-Projection-Role (EPR). These two interweaving developmental paradigms form the core of creative group work with children. Rather like the chains of DNA, NDP and EPR create curls and swirls in how we think about the creative play process (Figure 1.1) and how we apply it with groups (and individuals). Above all, the emphasis is on playfulness and its essential contribution to the health of children.

Figure 1.1 Swirls of NDP and EPR

NDP and EPR can be facilitated for social and emotional growth, particularly with children who struggle with their communication and behaviour, and those with developmental delay. Many of these children will probably have attachment difficulties and this book shows that applying NDP and EPR can encourage attachment and the process of reparenting. It is about the therapeutic facilitation of creative individual and group work to enhance personal and social strengths.

NDP and EPR are ‘value free’: that is, they do not rely on a particular school of psychological theory or model of therapy. Being based on detailed observation, they can be integrated into any psychological model or therapeutic or educational practice. Yet there is an emphasis on what the child can do, rather than their deficit. Positive psychology (Seligman, 2002) continues to influence the development and application of NDP and EPR.

Description of NDP and EPR

Play and attachment

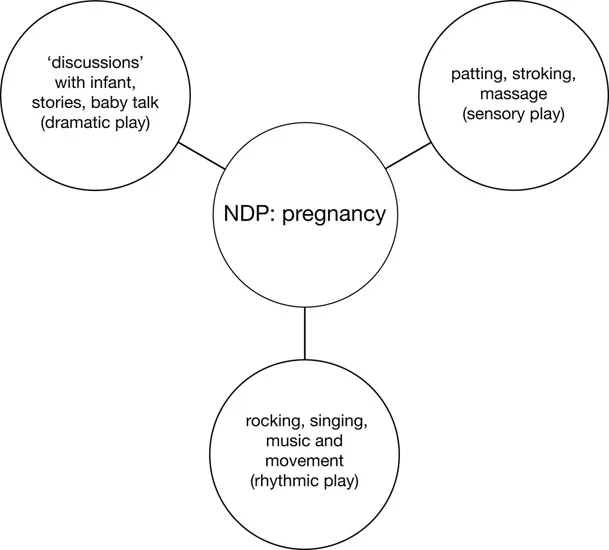

As you saw in the Introduction, play is at the heart of the attachment between baby and mother (or primary carer). Playful interactions reinforce the attachment relationship and enable mothers to fine-tune their reactions and responses. The playfulness starts during pregnancy and continues after the baby is born (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Neuro-Dramatic-Play: pregnancy

Mothers can be encouraged to be playful during pregnancy, six months before birth.

Child birth itself is a very messy, slimy procedure and medical staff are realising that babies do not need to be cleaned up immediately but placed on their mother’s chest for close contact.

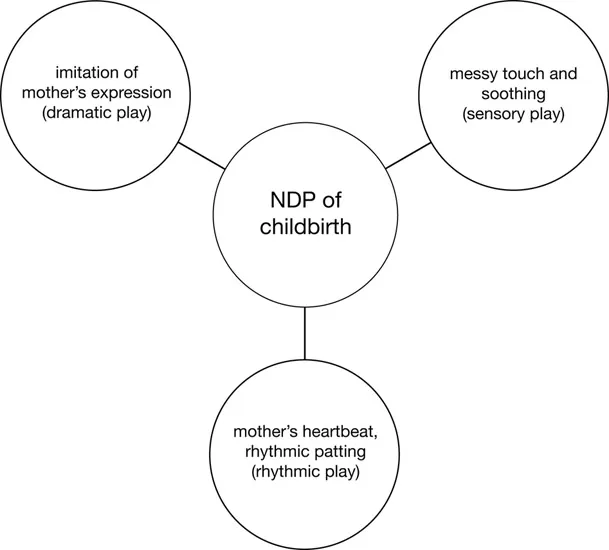

Within a few hours of birth, babies are already trying to imitate the expression of their mother’s face, following her voice round the room, and responding to her touch and heartbeat (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 NDP of childbirth

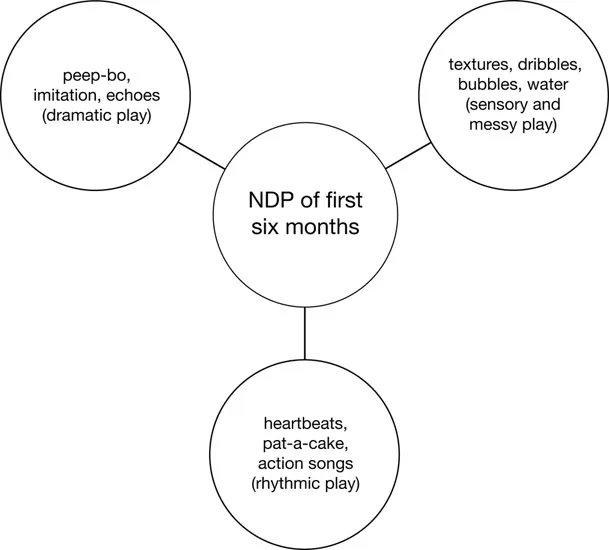

Sensory, rhythmic and dramatic play continue during the first six months after the birth. This is crucial for strengthening the attachment and providing the ‘safe body’ in the ‘safe place’ (Figure 1.4).

However, if these stages have not happened because of rejection, abandonment, neglect or abuse, it is essential that play activity (or, in serious situations, play therapy) are available to rework these early stages.

Figure 1.4 NDP of first six months

NDP is the earliest embodied experience that starts in infants, from six months before birth, and continues until six months after birth. It is characterised by ‘sensory, rhythmic and dramatic play’ and influences the growth of healthy attachments (Jennings, 2011). It is an expansion and extension of the Embodiment stage of EPR (which begins at birth and continues up to thirteen months), which is the most significant growth period for children. The greatest impact on the brain–body connection occurs during these early months.

Sensory play is important because many individuals’ senses will have been distorted through their abusive experiences. Messy play (fingerpaints, sand and water, sticky dough) assists individuals to express the mess and chaos of their feelings and, eventually, to create some order. Other sensory experiences are important such as providing a range of fabrics with different textures, a variety of essential oils, and, of course, hand cream.

Rhythmic play through drumming, singing, clapping and dancing allows individuals to rediscover their rhythm of life. Many individuals with PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) need to rediscover their inner rhythm, which is often displaced in trauma. Even breathing rhythm becomes panic-breathing but breathing in and out to a gentle drum beat can help the individual feel a greater calm.

Dramatic play through interactive stories, hide-and-seek, monster play and masks can help children and teenagers make sense of their experiences. Monster play (McCarthy, 2007) assists individuals to overcome their feelings of helplessness when they are overwhelmed. The ‘monster’ has destructive qualities of causing shame, blame and guilt, as well as night fears and nightmares. Becoming the monster is the first step to reduce its power!

A child develops security and trust through the early physical attachment of NDP, which then flows into a relaxed, attuned relationship (Erikson, 1965, 1995). Through these embodied experiences, the infant is establishing interactive communication through touch and sound, and rhythmic and ritualistic repetition.

These body-focused activities are essential for the development of the ‘body-self’: we cannot have a body image until we have a body-self (Jennings, 1998). A child or teenager needs to be able to ‘live’ in his or her body, which grows from being a secure part of the mother’s body. The progression is from being inside the mother, to being closely attached to the mother, and then gradually becoming independent, with the opportunity to resume physical contact, when desired or when fearful. This will establish the infant’s security to try to walk and to feel confident about moving in space. This progression can also be described as the three circles of attachment:

- the circle within the womb

- the circle in mother’s arms

- the symbolic circle when the mother ‘holds’ the infant in her consciousness and is attuned to changes in moods and needs.

These circles are circles of security and are crucial for safety and containment, especially when there is a traumatic experience.

It is essential to remember that the body houses physical well-being, sensory development and creative expression (Jennings, 2016).

The primacy of the body in play and drama

Most of our early physical and bodily experience comes through our proximity to other people – our attachment to our mothers or carers. We are cradled and rocked as we cooperate with rhythmic rocking and singing. Babies respond and mothers respond again because there is a collaborative approach to physical expression. Already the movement takes on some ritual or risk qualities: on the one hand, we have ritualised rocking movement and, on the other, bounce up and down with glee. Ritual and risk are the dual components of early physical play, where infants feel safely held and contained but, contrastingly, enjoy the thrill of the ‘danger’ (Jennings, 1998).

The body is the primary means of learning (Jennings, 1990) and all other learning is secondary to that first learned through the body. Therefore, children with early difficulties need extended sensory and physical play in order to rebuild a healthy and confident body. This includes children with developmental delay, children on the autistic spectrum, and children who have been abused, neglected and rejected.

Sensory processing condition

Children who have difficulty processing their sensory input can be helped with a gradual exploration of a range of sensory materials. Some children have what is now termed ‘sensory processing disorder’, or what I prefer to call ‘sensory processing condition’ (other terms include ‘sensory dysfunction’ and ‘sensory defensiveness’).

We live in environments that are often overstimulating with lights, screens and flashing images. Sensory processing condition means that some children’s brains have difficulty processing all of the sensory input, which may result in a range of behavioural struggles:

- ’melt down’

- avoidance of leaving the floor

- painful experience of even light touch, brightness and lightness, even on a dull day.

Certain foods may be avoided, as well as certain fabrics (Heller, 2003; Godwin Emmons & McKendry Anderson, 2005; Lloyd, 2016). Historically, difficulties with sensory processing were considered part of the autistic spectrum condition and it has only recently been considered it in its own right. Sensory processing condition can be very mild, such as irritation from labels on clothing, to more severe when all of the senses can be affected. It may result in children who cannot sit still and are always fidgeting or restless, who stumble frequently and bump into things, or have difficulties with the right amount of pressure when writing or drawing. These difficulties can be caused by early neglect and/or be neurologically based.

For example, in Romanian orphanages where small and older children were left tied to beds or cots, gross forms of sensory processing difficulties resulted. The children’s sensory systems were severely impaired and it took intensive small group work through movement and play to bring about some improvements.

The staff and I took a group of teenagers who had been rescued from one of the notorious institutions ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Author’s acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Practical play and drama

- Chapter 2 Play and attachment

- Chapter 3 Sand play: sensory play and messy play

- Chapter 4 Movement, dance and games

- Chapter 5 Projective play and calming methods

- Chapter 6 Learning to fly and keeping safe

- Chapter 7 Dramatic play, roles and drama

- Chapter 8 Masks and puppets

- Appendix 1 Assessment

- Appendix 2 Play outdoors

- Appendix 3 Messy play recipes

- References and further reading