- 247 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Death, Decomposition, and Detector Dogs: From Science to Scene is designed to help police investigators and Human Remains Detection K9 handlers understand the basics of forensic taphonomy (decomposition) and how to most effectively use a human remains detection (HRD) K9 as a locating tool. The book covers basic anatomy and the physiology of canine

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Death, Decomposition, and Detector Dogs by Susan M. Stejskal in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Derecho & Ciencias forenses. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Know the Nose

Introduction

As part of a detection team, the human remains detection (HRD) K9 handler should be able to describe how a dog is able to work as a locating tool (Figure 1.1). This chapter is a review of the canine olfactory system, and the basics of the anatomy and physiology of scent perception in the dog.

Perception

Although humans use all five senses, we depend very heavily on our sense of sight (Figure 1.2). When we travel through busy streets, we are confronted with moving traffic, lights blinking off and on, and the faces of people passing by. We read body language and facial expressions to guide us in our interactions with those people. Therefore, we depend heavily on our eyes.

Obviously dogs also use their eyes, but they go through their day reading and reacting to their environment through their sense of smell. Instead of enjoying the beauty of a sunrise, a dog enjoys the smell of a fresh pile of bunny poop—something a human thankfully can’t really do. Dogs are designed to use their noses.

Figure 1.1 The tool!

Figure 1.2 Visual overload for people? Is this what it’s like for a dog nose?

Anatomy

The olfactory system is basically the same in humans and dogs, but there are obviously some differences that allow dogs to do what they do. The goal is to get air that contains odor chemicals to the cells that detect it and then send the message to the brain where that input is processed. The basic parts of the olfactory system are the nostrils, nasal turbinates, olfactory sensory cells, olfactory nerves, and the brain. The Cadaver Dog Handbook by Rebmann, David, and Sorg (2000) provides a detailed description of the canine olfactory system.

First, breathing is a part of olfaction. Air carrying odor chemicals is inhaled through the nostrils or nares (Figure 1.3). When humans breathe, the air goes straight in and then straight out. A dog’s nostrils are unique because they are capable of flaring or moving as the dog exhales. As a dog exhales, the exhaled breath is directed off to the side. Unlike humans with our stubby, straight nostrils, the dog doesn’t rebreathe much of the same air it just exhaled. There is a fresh supply of air with every breath they take. The nostrils are divided by a septum and so are two separate bony structures.

Figure 1.3 The air carrying odor chemicals is inhaled through the nostril or nares.

Once air passes into the nostrils, it moves through the nasal turbinates, a highly coiled pathway surrounded by bone. The coiled formation of the turbinates creates a large surface area with an extensive blood supply. That blood supply helps to warm, filter, and moisten the air after it’s inhaled.

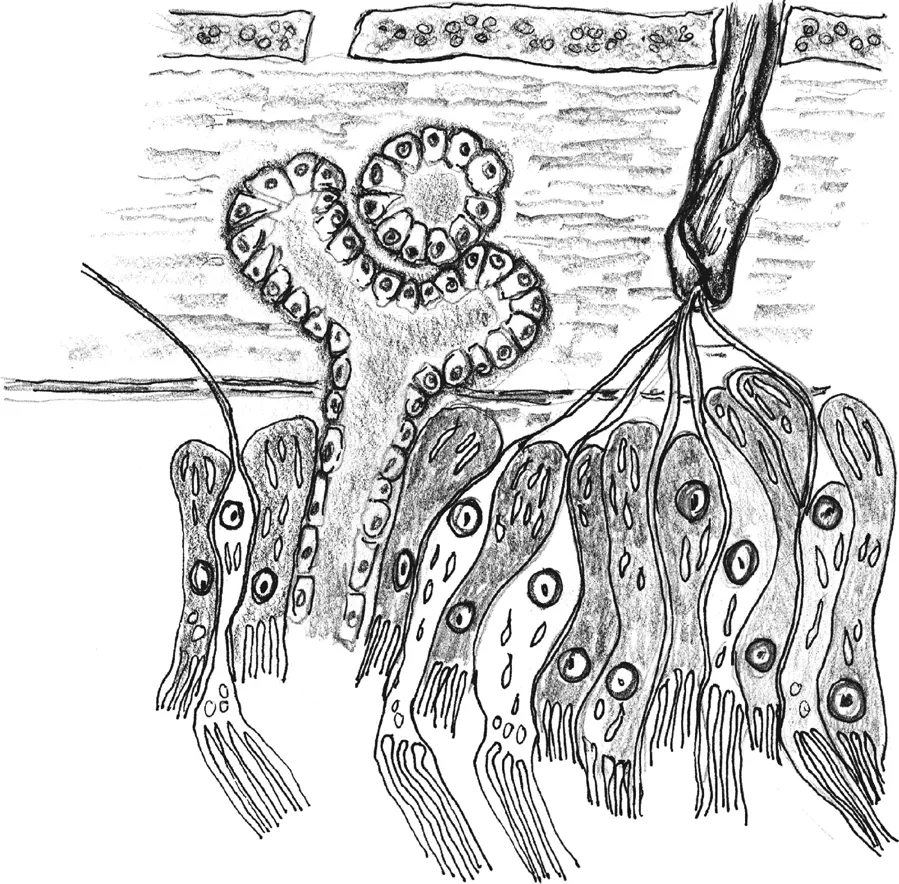

The turbinates are lined with different kinds of cells that help support the olfactory sensory cells. They include the goblet cells and pseudostratified, ciliated, epithelial cells (Figure 1.4). Let’s look closer. The goblet cells produce mucus or phlegm. This mucus coats the top surface of the cells in the turbinates. The epithelial cells have cilia or hair-like projections that stick above the cells into the mucus layer. The job of these two kinds of cells is to filter incoming air by trapping dust or other small particles in the mucus, and then the cilia brush or push the mucus down toward the pharynx (near the back of the mouth) where it can be swallowed, sneezed, or coughed out.

The olfactory sensory cells (OSCs) are very different from the other cells (Figure 1.5). They are actually bipolar nerve cells that have cilia on one end while the other end works as a nerve that sends information to the brain. The OSCs interact with incoming odor chemicals, allowing olfaction to happen. How it works will be covered later.

Regular breathing in the dog allows some of the air to get to the OSCs. When a dog pants or breathes through its mouth, even less air gets to the OSCs. Any detection dog handler can describe the changes that they see in their dog when the dog is onto the odor they are trained to detect; the breathing changes to sniffing (Figure 1.6). Sniffing is described as a “disruption of normal breathing … a series of rapid and short inhalations and exhalations” (Correa, 2005). But, compared to regular breathing, a dog’s sniffing causes something special to occur. First, the outward puff of air can raise a cloud of dust, freeing the odorant chemicals (Goldblatt, 2010). Sniffing causes the inhaled air to become trapped in the nasal pocket, a cave-like area formed in the nasal turbinates where many of the OSCs are located. A single sniff can cause an accumulation of odor-containing air to become trapped near the OSCs. The combination of new air coming in and collecting in the nasal pocket allows a dog to detect and recognize minute amounts of odor.

Figure 1.4 Light-colored olfactory sensory cells surrounded by darker support cells and mucous secreting goblet cells. (Adapted from Hole, J. W. 1990. Human anatomy and physiology. Dubuque, IA: Wm. C. Brown Publishing, Chap. 12.)

Figure 1.5 Closer view of the sensory cell with cilia at the bottom and nerve at the top leading to olfactory nerves. (Adapted from Hole, J. W. 1990. Human anatomy and physiology. Dubuque, IA: Wm. C. Brown Publishing, Chap. 12.)

Figure 1.6 Sniffing is different than breathing.

Dogs also have a unique nasal airflow pattern that occurs during sniffing; each nostril can get separate odor samples that, after being processed in the brain, allow a dog to localize the source of the odor (Craven, Patterson, and Settles, 2009). This is similar to how we are able to tell where a sound may be coming from with our ears.

Odor Detection and Olfactory Receptor Cells

As previously described, scent or odor is made up of different chemicals trapped in air. The chemicals are volatile, meaning they evaporate easily at room temperature. The chemicals get carried in with air, transfer to the water in the mucus layer in a dog, and then come in contact with the cilia of the OSCs. It is the unique design of the OSCs that lets olfaction take place.

Olfactory sensory cells are actually chemoreceptors—a type of nerve cell that is specially designed to interact with chemicals. These olfactory receptors (OR) are part of the cilia on the OSCs, located for easy access to incoming air.

A simple way to describe how olfaction works is to compare OSCs to taste buds, another type of chemoreceptor (Hole, 1990). In the human, there have been five basic types of taste buds described as being arranged in specific locations on the tongue (Berkowitz, 2011). If salt encounters the “sweet” taste bud, nothing happens. If salt meets a salt taste bud, then the chemical interacts with the receptor and produces an electrical impulse that is sent to the brain. We now detect the taste of salt.

This same explanation can be used with odor detection. A chemical is carried in with inhaled breath, probably as a gas, dissolves and gets picked up in the watery part of the nasal mucus, and comes into contact with the receptor-containing cilia on an OSC. If it is the right receptor for that particular chemical, binding occurs. A “lock and key” process takes place (Figure 1.7). When a chemical in water vapor (the key) gets stuck in the mucus, it reaches the OSC cilia and then the OR (the lock). If the right key fits the lock, the OSC chemistry changes and produces an electrical current or signal. That signal travels up the nerves to the olfactory bulb and then to centers in the brain where the odor is processed.

It appears that not all ORs are the same. Two researchers (Buck and Axel) won a Nobel Prize in 2004 for cloning an olfactory receptor. This work provided a framework to understand how the olfactory system really works. It is believed that each OR is probably unique and has a single chemical receptor. For a chemical to bind to a receptor, it is probably affected by the size, shape, structure, and concentration of the chemical odorant (Lesniak et al., 2008). According to Goldblatt, Gazit, and Terkel (2009), each OR “expresses only one receptor protein.”

Figure 1.7 Key (chemical in air) fits in lock (receptor in olfactory receptor) = open door (or the beginning of the chemical to electrical signaling to brain).

Figure 1.8 Partial dog skull, illustrating nasal cavity and anterior brain. View from side with nasal septum removed to show the turbinates. (From Rebmann, A., E. David, and M. Sorg. 2000. Cadaver dog handbook: Forensic training and tactics for the recovery of human remains. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. With permission.)

There are >1000 genes that control the ORs of the OSCs in the dog, meaning there is a great degree of variation seen in the OR genetic code among individual dogs and breeds (Tacher et al., 2005). The number and types of receptors vary widely among dogs.

The electrical information is carried from the OSCs by olfactory nerves to the olfactory bulb (OB) in the brain (Figure 1.8). The OB, described as a relay station for electrical signal conduc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- About the Author

- 1 Know the Nose

- 2 Forensic Taphonomy: Breaking Down Is Hard to Do

- 3 Bugs, Bodies, and Beyond

- 4 Making Sense Out of Scent: The A, B, C, Ds

- 5 Earth, Wind, and Odor

- 6 Teaching Old Dogs New Tricks Using New Technology

- 7 A Picture Is Worth a Thousand Words

- 8 Beginning of the End

- Index