1

DEVELOPING CO-WORKERSHIP IN ORGANISATIONS

Karin Kilhammar

‘Co-workership’ is a concept which has become more and more widespread in the Swedish workplace. This can be confirmed by the products sold by consultants who offer solutions for ‘co-workership development’ and other internal organisational arrangements in an effort to develop co-workership amongst employees. In many HR policy documents, co-workership receives a natural, and often prominent, treatment. Sometimes, such documents are titled as ‘co-workership policy’ or ‘co-workership ideas’.

The concept of ‘co-workership’ and its use provide us with clues about the importance of the employees for an organisation and its operations. When we consider the HR department’s role in showing how important the employees are for the organisation and their support of the development of human resources, it is quite clear that the development of co-workership is an obvious area for HR specialists to work in. However, despite the fact that ‘co-workership’ is a well-established concept in Sweden and neighbouring countries, it can be interpreted by some as somewhat vague. ‘Co-workership’ is both a multifaceted and a flexible concept, which results in a variety of interpretations and different forms of implementation in different organisations. In this chapter, we examine what is usually assigned as the content of this concept and the various conflicting interpretations that it can give rise to. When co-workership is developed in cooperation with the organisation’s management team, then issues of leadership that are relevant to the development of a properly functioning co-workership are affected. Furthermore, this chapter examines the factors which promote or hinder the development of co-workership, and the important issues that should be considered when co-workership development is to be implemented in an organisation.

‘Co-workership’ – a multifaceted and flexible concept

When I lecture on ‘co-workership’, I usually ask the audience what they think the concept is about. Often, the answers are tentative and diffuse, but on the whole, certain aspects repeatedly come to the fore. The content assigned to the concept during these discussions is congruent with the common features apparent in the interpretation of the concept which I have identified in my research in this area.1

Fundamental to co-workership is that focus is placed on the employees and that it is concerned with how employees deal with their role within the organisation. By using the concept, the employees’ importance for the organisation is revealed. It places demands on the employees as well as provides opportunities for their development. The most central aspect of co-workership is taking on responsibility. The discourse2 on co-workership emphasises individual responsibility, meaning that the employee is active and takes the initiative, even though group responsibility is also included as a dimension to this. Furthermore, participation and influence are also considered to be fundamental to co-workership, which can be seen as a precondition to taking on responsibility. To be able to take on responsibility and to contribute to the organisation’s development, the employees need to be familiar with the organisation and have a complete, holistic overview of the organisation (Kilhammar, 2011).

One way to describe co-workership is to claim that it deals with the employees’ relationships at work. This includes relationships with other people who employees interact with at work, for example, managers, clients, and colleagues, but also the employee’s relationship with work itself, with the employer and organisation, and last but not least, the employee’s relationship with himself/herself and his/her own private life (Hällstén & Tengblad, 2006).

Despite the fact that there exist common features which most people agree with in the various interpretations of the concept of ‘co-workership’, there are differences in how these features are ranked. These differences in ranking, or emphasis, tend to be related to the perspective that is taken on co-workership; there is a clear difference between the employer’s perspective and the employee’s perspective in this regard. The results of previous research (Kilhammar, 2011) show that those who represented the employer emphasised taking on responsibility as part of the concept of ‘co-workership’ more so than the employees, and they also associated participation and influence with taking on responsibility more clearly than the employees. The employees took the position that participation and influence were of value in themselves to a higher extent. There were also differences in the relationships that were emphasised. From an employer’s perspective, the employee’s relationship to managers, the employer, and the work itself were considered to be central, whilst the employees primarily associated co-workership with their relationships to their colleagues.3

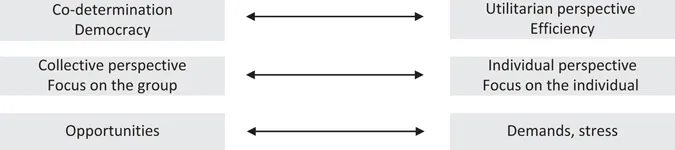

Three areas of tension can be used to further clarify the differences in interpretation of the concept, in cases where the interpretation and the realisation of co-workership differ (see Figure 1.1). These areas of tension form a continuum between two poles. While both poles are present in interpretations about co-workership, one pole may be more dominant than the other.

FIGURE 1.1 The areas of tension found in the various interpretations of co-workership (Kilhammar, 2011: 222).

The first area of tension represents the orientation of ‘co-workership’ and how the concept is used. Is the primary goal of co-workership one of participation, where democratic values are guiding lights, or is the aim of co-workership to achieve the organisation’s goals and advance efficiency? In the second area of tension, a collective perspective is contrasted with an individual perspective. The individual perspective emphasises each individual’s taking on responsibility and the individual’s actions, whilst the collective perspective focuses on the group and how the group functions together. The third area of tension represents how the notion of ‘co-workership’ is conceived as impacting on the individual: whether ‘co-workership’ is considered as providing opportunities for development and is something that makes the employee stronger or whether it is considered as a source of increased demands, leading to stress and, in the long run, a cause of illness for the employee (Kilhammar, 2011).

As demonstrated above, ‘co-workership’ is a multifaceted concept. A superficial consideration of the concept may lead one to think in one particular direction, but a deeper analysis shows that things are more complicated. Opinions about what co-workership represents can differ between different actors within the one and the same organisation. Before large-scale efforts to develop co-workership within an organisation are made, it is thus important to initially make the concept clear to everyone involved and to come to an agreement about its content and the type of co-workership which one wants to feature within the organisation.

‘Co-workership’ is also a flexible concept. Within the framework of ‘neo-institutional theory’, we are confronted with the metaphor of popular ideas journeying into, and between, organisations (Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996). Organisations adopt fashionable ideas and translate these ideas so that they suit their own needs. Doing so creates legitimacy and demonstrates that the organisation is ‘keeping up with the times’, whilst it can also generate ideas that might solve certain problems that the organisation faces.

The growth and use of ‘co-workership’ over time

The concepts ‘co-worker’ and ‘co-workership’ have changed over time, according to different purposes, and have thus been endowed with different meanings. During the 1950s and 1960s, these concepts were used from a labour union perspective, with the aim of opening up workplace democracy in additional areas where the employer and employee could develop common interests (Stråth, 2000). Accordingly, we note that co-determination and other democratic values were central features at that time.

During the 1970s, employers appropriated the concept of ‘co-workershp’ and used it from their perspective. This entailed binding employees closer to the company so that their work became part of their identity. A further aim with this was to weaken the employees’ strong labour union membership by creating individualised employees (Mahon, 1994; Stråth, 2000, 2002).

It was only during the 1990s that ‘co-workership’ first began to be used more widely in Sweden. The trend at the time included ‘flat’ organisational structures with a limited number of managers, which demanded that the employees took on a greater amount of responsibility and participated at the workplace in a way that was different, compared with earlier decades. One result of this change was that the employees, to some degree, took on some of the work assignments which had previously been performed by managers (Hällstén & Tengblad, 2006). Co-workership was sometimes used at the time as a means to change employees’ attitudes so that they would adapt to the new working conditions which were being introduced (Jonsson, 2003).

Whilst co-workership during the 1990s primarily resulted in employees taking responsibility for tasks which traditionally had been part of the management’s responsibility caused by the very flat leadership structures prevalent at the time, in the 2000s, we note an increased emphasis on reciprocity between co-workership and leadership, and the interaction between these two groups (Tengblad, 2011). How co-workership is ultimately realised is dependent on how the management is structured, and vice versa. Management structures are needed, but management leaders need to take on different roles, than previously.

The leadership that is needed to develop co-workership

How do we describe the leader’s new role as we examine ‘co-workership’? What is demanded of management if the goal is to achieve properly functioning co-workership within an organisation? A fundamental condition for this is that management must adapt its leadership role so that it is in total agreement with the form of co-workership that the organisation wishes to achieve. In other words, it is necessary that management be compatible with co-workership. Managers also need to possess the ability to drive the development of co-workership forward within their domain of responsibility and create the necessary conditions for learning (Kilhammar & Ellström, 2015).

The actual manner in which the management structure needs to be arranged so as to achieve total agreement with co-workership is, of course, dependent on the form of co-workership which is desired. Notwithstanding this, there are several fundamental features of management that are necessary to achieve a developed form of co-workership.

First, the management needs to practice a leadership that is generous and delegatory. If employees are to take on increased levels of responsibility and begin to influence the organisation, then managers need to allow for this and delegate certain assignments to the employees and create conditions where taking on responsibility is possible for the employees. This will not happen if the manager is too authoritarian and controlling. Instead, the manager should provide space for the employees’ participation, their exercise of influence within the organisation, and even their independence.

Second, a supportive, coaching leadership style by the management is crucial. Employees may also need active support in their roles and in the development of co-workership. It is thus of importance that managers are percipient, support the professional development of the employees, and provide them with constructive criticism.

Finally, management leadership must act as a guide and set standards. Even though the development of co-workership encourages taking on responsibility and independence, leaders are needed who possess a complete overview of the issues at hand, delimit the scope of the work to be done, and provide the work with a clear direction. From the employee’s perspective, this may entail that the manager possesses the ability to lead the whole group of employees, in the same direction (Kilhammar, 2011).

Strategies for developing co-workership – two examples

It is not uncommon that centrally coordinated, large-scale efforts are made within organisations, where more or less structured programmes for employee development and the development of co-workership are implemented. How these programmes are implemented and for what purpose can vary, however. This is illustrated by Kilhammar’s (2011) study of two initiatives for the development of co-workership in two different organisations and how these initiatives played out.

These organisations had a common, basic motive for the implementation of co-workership, namely to promote the employees’ contribution to the effectiveness and quality of the operation of the organisations. However, certain differences were identified; in part, with respect to which concrete problems needed to be solved in each organisation, and, in part, with respect to perceptions of how the goal of co-workership would be achieved. These differences demonstrate the flexibility found in the concept of ‘co-workership’, where its content and implementation are adapted to an organisation’s specific needs (Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996).

In one of the organisations, a county council healthcare provider, the point of departure for the implementation of co-workership was the perceived need for development and participation that was assumed to be included in what “the modern worker” represented. This move was in concert with the council’s wish to provide an attractive workplace for its employees so as to ensure the long-term provision of competent employees. At the time, the council had experienced problems with many employees who were on long-term sick leave. The belief was that the development of co-workership would improve the workplace environment. This, in turn, established the conditions for the employees to deliver good quality work, which was also expected to result in the creation of increased quality and efficiency within the organisation, and thus the provision of better healthcare for the patients. The purpose of the development programme was to provide the employees the conditions within which they could assume responsibility and perform the work well.

The other organisation, a state-owned service company, had undergone a large-scale restructuring as two separate companies were merged together. In conjunction with this restructuring, a new way of working, shared service, was introduced, whic...