![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The need for organisational resilience

War is

a grave affair of state;

It is a place

Of life and death.

A road

To survival and extinction,

A matter

To be pondered carefully.

(Tzu 2008, 1)

CONTENTS

Von Clausewitz and De Jomini: the art of war

Organisational resilience

The need for resilience in 1940

Von Clausewitz and De Jomini: the surprise

De Jomini: grand tactics and battles

Offensive battles

Order of battle

Common explanations

Technical specifications of the tank

Competing concepts of resilience

Limitations of the book

Armageddon

Notes

References

On May 15th 1940, the British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill, while he was still in bed, was called by Paul Reynaud, his French counterpart:

He spoke in English, and evidently under stress. ‘We have been defeated’. As I did not immediately respond he said again: ‘We are beaten; we have lost the battle.’ I then remarked: Surely it can’t have happened so soon? But he replied: ‘The front is broken near Sedan; they are pouring through in great numbers with tanks and armoured cars.’

(Jackson 2003, 9)

On May 10th, Nazi Germany commenced its offensive in the west, with the invasion of Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg and France. On May 13th, German forces crossed the river Meuse and broke through the French defences. The author of the ‘Little Prince’, who was a pilot at that time, set off on a reconnaissance on May 22nd 1940:

We stand against the enemy as one man against three, one plane against ten or twenty, since Dunkerque, one tank against a hundred. We have no time to meditate upon the past. We are engaged in the present. The present is as it is. No sacrifice, ever, anywhere, can possibly slow the German advance.

(Antoine de Saint-Exupéry 1942, 46)

The Fall of France in May/June 1940 at the hands of Nazi Germany is one of the great surprises of the twentieth century. The disparity of strength between the French and German disposition of forces favoured the Allies1; yet the weaker party prevailed. Germany inflicted one of the ‘strangest’ defeats in military history. The reason for the defeat of France in 1940 lends itself to renewed analysis from a management perspective.

The purpose of this book is not to replicate history or to improve its accuracy. It seeks to evaluate this piece of history through the eyes of management, a function that enables modern organisations to accomplish goals and objectives using available resources efficiently and effectively in the face of a range of adversities. In this respect, as Von Clausewitz suggested, history is

meant to educate the mind of the future commander, or, more accurately, to guide him in his self-education, not to accompany him to the battlefield; just as a wise teacher guides and stimulates a young man’s intellectual development, but is careful not to lead him by the hand for the rest of his life.

(quoted in Kennedy and Neilson 2002, 26)

VON CLAUSEWITZ AND DE JOMINI: THE ART OF WAR

This book will provide excerpts from two groundbreaking works on theories of war: On War (Von Clausewitz 2011) and The Art of War (De Jomini 2008). Both theories appeal to military planners and organisational strategists alike, although Von Clausewitz is more well known to both.

Carl von Clausewitz was born in 1780 and rose through the ranks of the Prussian army, with an interlude with the Russian army that led him to experience the Napoleonic Wars at Borodino. The Battle of Borodino, fought on September 7th 1812, during the invasion of Russia by Napoleonic forces, pushed the Russian army back from its positions, but the only gain was a tactical victory. With no capitulation of the Russian army in sight and the French forces ill-prepared for a prolonged stand-off, it marked the beginning of the end of the Russian campaign for Napoleon Bonaparte.

Von Clausewitz rejoined the Prussian army, mesmerised but also disillusioned by the Napoleonic way of thinking. He commented on Borodino that in the whole battle there was not a single trace of an art or superior intelligence.

He was transferred to an administrative post in the Prussian army and found time to write down his impressions and reflections on this remarkable period of warfare. The book On War remained unfinished when Von Clausewitz died in 1832, but his works were published in 1835 by his widow.

De Jomini was born in 1779, joining the French army in 1797. He held staff positions under Napoleon and Ney but was only promoted to general de division when he joined the ill-fated campaign against Russia on June 28th 1812. He gained first-hand experience of the Napoleonic method and its failure during the retreat from Moscow, which concluded in December 1812, with the loss of around 300,000 French, 70,000 Poles, 50,000 Italians, 80,000 Germans and 60,000 from other nations. His thoughts about strategy were originally published in 1830, with a revised edition eight years later.

Since then, Von Clausewitz and De Jomini have been seen as the cornerstones of military science and yet not without substantial criticism of their work. One aspect of the criticism of Von Clausewitz relates to his preoccupation with the political sphere as a strategic variable in war, whereas De Jomini is said to focus his attention on operational and tactical details, lacking a ‘bigger picture’ understanding.

Both theories were developed with an understanding of the current context, not with an imaginative, futuristic one. Military technology did not, in the Napoleonic era, provide military planners with opportunities to kill over a great distance, in stealth, and to the far greater extent that it does now. Logistics were constrained by the means available for transporting men and materials (e.g. ammunition) over distance. The opportunity to exploit the sky was in its infancy, with some early attempts to use hot-air balloons for observation.

Nevertheless, the art of war feeds on human ingenuity to develop novel ways of subduing hostile forces. This does not make those past theories redundant. They serve rather as a point of reflection, one that makes one think about their usefulness in the current context. Hence, general principles cannot be a blueprint to be taken for granted and applied universally. Instead, they should trigger a thought process. Like the concept of Organisational Resilience as a translation of military concepts, evolved over centuries, any theory is an expression of human creative skills, it is an art. Von Clausewitz argued,

All thinking is indeed Art. Where the logician draws the line, where the premises which are the result of cognition stop – where judgement begins, there Art begins. But, more than this, the mind’s perception is judgement again, and consequently Art; and at the last, even the perception of the senses is also Art. In a word, if it is impossible to imagine a human being possessing merely the faculty of cognition, devoid of judgement or the reverse, so also Art and Science can never be completely separated from each other. The more these subtle elements of light embody themselves in the outward forms of the world, so much the more separate appear their domains; and now once again, where the object is creation and production, that is the province of Art; where the object is investigation and knowledge Science holds sway. Because of all this it is self-evidently more fitting to say Art of War than Science of War.

(Adapted from Von Clausewitz 2011, 50)

ORGANISATIONAL RESILIENCE

History is most useful when explored through the eyes of those who contributed to the development of the art of war, such as Von Clausewitz and De Jomini. Depth of study is achieved by examining a campaign or battle in detail. In this respect, we will focus in depth on the German campaign in the west in May/June 1940 but will also add insights into other campaigns and battles in the Second World War (WWII). All attempt to be thought-provoking in their own right, resonating with many of today’s challenges about how to be resilient.

Organisational Resilience is a state to be established and maintained to counter the effects of two key environmental conditions: uncertainty and complexity.

UNCERTAINTY

Uncertainty is associated with a lack of knowledge about how the future will unfold, leading to the inability to pursue an appropriate organisational response. We cannot establish with confidence how an environment may change or what impact that may have on the function of our own organisation, and thus we cannot define a response to it to either prevent it from happening or bounce back from it.

COMPLEXITY

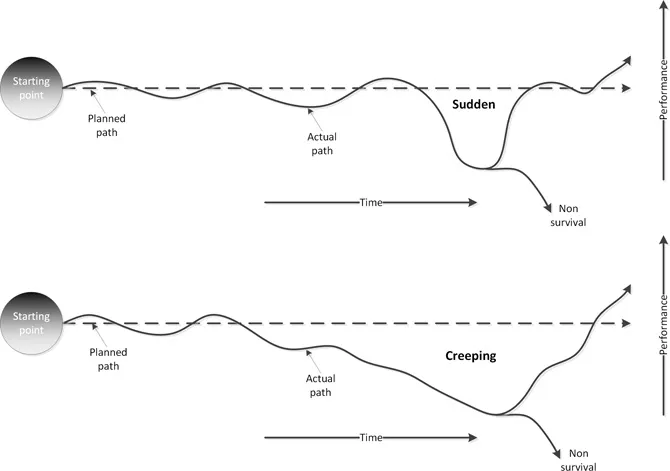

As shown in Figure 1.1, in a tightly-coupled system, interdependencies between elements mean that incidents can build upon each other and escalate rapidly, triggering a sudden crisis. Loose coupling implies that points of failure are relatively independent, and buffers or slack between them can limit the effects of interconnectivity. Loose coupling provides ‘breathing space’ to contain a creeping crisis, thereby preventing them from gradually destabilising the whole.

To address the challenges of uncertainty and complexity, organisational resilience is often referred to as an ability to bounce back from adversity (Burnard and Bhamra 2011). Originally, the resilience literature emerged from studies of ecological systems noted for having a persistent absorptive capacity to deal with disturbances, followed by a reconfiguration of the system (Holling 1973; Gunderson 2000; Warner 2011).

From a socio-ecological perspective, resilience is associated with the ability of a system to retain function when perturbed (Carpenter et al. 2001). The concept of disaster management (Paton et al. 2000), for example, focusses primarily on recovering from a crisis, largely ignoring the pre-crisis incubation phase (Turner 1976).

Another strand is one of Organisational Resilience (Home and Orr 1997; Hamel and Välikangas 2003; Pagonis 2003) – not dissimilar to the body of literature on resilience engineering (Hollnagel 2006; Woods 2006) – which sees resilience as the fundamental property of an organisation to adapt to the requirements of the environment’s variability. From a socio-psychological view, a further body of literature has emerged which considers Resilience as an outcome, based on an attentional state of mindfulness (Weick and Sutcliffe 2006, 2015). Mindfulness is

the combination of on-going scrutiny of existing expectations, continuous refinement and differentiation of expectations based on newer experiences, willingness and capability to invent new expectations that make sense of the unprecedented events, a more nuanced appreciation of context and ways to deal with it, and identification of new dimensions of context that improve foresight and current functioning.

(Weick and Sutcliffe 2001, 32)

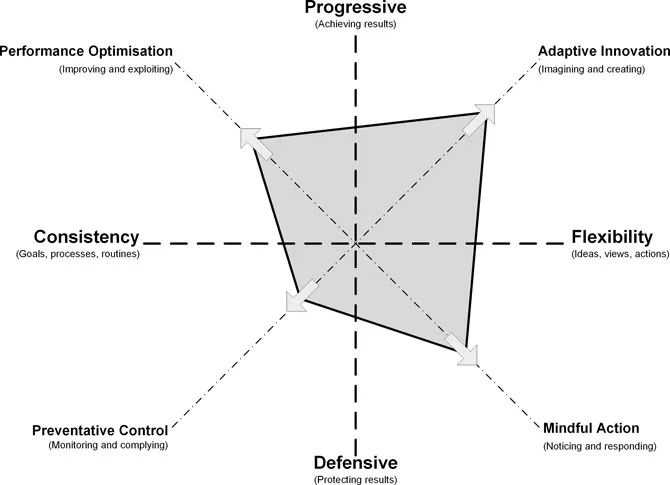

What these bodies of literature have in common are the principal properties of resilient organising (see Figure 1.2). Resilient organisations may choose to be defensive, to protect their organisations from anything bad happening. They may be progressive in an opportunistic manner, pursuing consistency in goals, processes and routines as well as being flexible in their ideas, views and actions.