![]()

Part I

INTRODUCTION

![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Jason Monios and Rickard Bergqvist

INTRODUCTION

This chapter establishes the requirement for this textbook and introduces the topic of intermodal freight transport and logistics, identifying its role within the broader area of freight transport, in addition to its place within logistics. The chapter provides a brief outline of policy issues as well as spatial descriptions of intermodal transport via corridors and nodes before moving on to the operational focus of this book. The chapter provides an overarching view of the key elements of intermodal transport operations and how they relate to questions of policy and planning. The structure of the book (operations, frameworks, analysis) is introduced and a brief outline of each chapter is presented.

THE ORIGINS OF INTERMODAL TRANSPORT

Multimodal transport refers to the use of more than one mode in a transport chain (e.g. road and water), while intermodal refers specifically to a transport movement in which the goods remain within the same loading unit. While wooden boxes had been utilised since the early days of rail, it was not until strong metal containers were developed that true intermodal transport emerged. The efficiencies and hence cost reductions of eliminating excessive handling by keeping the goods within the same unit were demonstrated in the first trials of a container vessel by Malcom McLean in 1956.* The initial container revolution, therefore, took place in ports, as the stevedoring industry was transformed over a few decades from a labour-intensive operation to an increasingly automated activity. Vessels once spent weeks in port being unloaded manually by teams of workers; they can now be discharged of thousands of containers in a matter of hours by large cranes, with the boxes being repositioned in the stacks by automatic guided vehicles. This in turn means that ships can spend a much higher proportion of their time at sea, becoming far more profitable.

As shipping and port operations were transformed by the container revolution, a wave of consolidation and globalisation took place. Shipping lines grew and then merged to form massive companies that spanned the globe. Container ports expanded out of origins as general cargo ports or were built entirely from scratch. Some existing major ports today show their legacy as river ports and require dredging to keep pace with larger vessels with deep drafts (e.g. Hamburg), whereas newer container ports are built in deep water, requiring not dredging but filling in to create the terminal land area (e.g. Maasvlakte 2, Rotterdam). The move to purpose-built facilities with deeper water severed the link between port and city, with job numbers reduced and those remaining moved far from the local community, altering the economic geography of port cities (Hesse, 2013; Martin, 2013).

Most of the new generation of container ports are operated by one of a handful of globalised port terminal operators, such as Hutchison Port Holdings or APM. This is the result of the trend towards consolidation across the industry in the decade leading up to the onset of the global economic crisis in 2008, in which many mergers and acquisitions took place in both shipping liner services and port terminal operations. There has also been much vertical integration, with shipping lines investing in port terminals (e.g. Maersk/APM and others). The increasing integration between shipping lines and ports has created an almost entirely vertically integrated system, from port to shipping line to port, within the same company. The inland part of the chain is the new battleground, but it is more complex than the sea leg.

As a result of these changing industry dynamics, ports changed from city-based centres of local trade to major hubs for cargo to pass through, with distant origins and destinations. This development was driven to a large degree by the container revolution, as distribution centres (DCs) located in key inland locations became key traffic generators. Port hinterlands began to overlap as any port could service the same hinterland. Shipping services were rationalised, with large vessels traversing major routes between a limited number of hub ports. Cargo was then sent inland or feedered to smaller ports. The introduction of new, larger vessels on mainline routes is initiating a process whereby vessels cascade down to other trades. The result is that feeder vessels are being scrapped at a higher rate than normal, and the order book for new builds is at a historic low.

Despite such consolidation in shipping and port terminals, the business of maritime transport remains highly volatile, not just cyclical but dramatically so, exhibiting widely divergent peaks and troughs. According to a senior executive from Maersk, ‘2009 for Maersk Line was the worst year we have ever had and 2010 was the best – that is not very healthy’ (Port Strategy, 2011). Therefore, port actors seek stability where possible, needing to anchor or capture traffic to make themselves less susceptible to revenue loss when the market is low. Inland transport is now the area where they seek to secure this advantage. This need to control inland connections is not just about physical infrastructure but institutional issues such as labour relations and other regulatory issues.

While the rise of intermodal transport originally related primarily to sea transport, the land leg was undertaken by all modes, which were also busy transporting domestic traffic. Before the nineteenth century, hinterland transport primarily consisted of sailing ships and horse-drawn wagons. During the nineteenth century, barge canal operations combined with horse or rail became more common, and there were even some early experiences with intermodal transport units (ITU). One of the first experiences of ITU was in England, where it was used for the transport of coke between road carts, barges and railcars. By the early twentieth century, rail wagons were put on seagoing vessels and trucks on rail wagons. Intermodal transport began, but there were still few systems that could carry a standardised load unit suitable for intermodal transport.

By the mid-twentieth century, the carrying of road vehicles by railcar, known as piggyback transport or trailers-on-flatcars (TOFC), became more widespread. This method of transport was previously introduced in 1822 in Germany, and in 1884 the Long Island Railroad started a service of farm wagons from Long Island to New York City (APL, 2011). As TOFC caught on during the 1950s, the use of boxcars declined. One reason why TOFC became popular was the improved efficiency of cargo handling and the end of break bulk handling. Between 1957 and 1992, the number of boxcars in the United States decreased from about 750,000 to fewer than 200,000 (APL, 2011).

The increasing integration of international and domestic transport was a result of globalised supply chains growing out of relaxed tariff and trade barriers as well as ever-cheaper sea transport. Inputs to manufacturers and even finished products were being imported at a growing rate from cheaper supply locations and, to overcome congestion and administrative delays at ports, shipping lines began to offer inland customs clearance. The bill of lading could now specify an inland origin and destination. These sites were variously known as inland clearance depots (ICDs) and ‘dry ports’. In the United Kingdom, so-called ‘container bases’ were established at key locations around the country in the late 1960s to handle containerised trade passing through south-eastern ports to and from inland locations in the north and centre of the country. These freight facilities were usually located next to intermodal terminals, but the actual transport mode could be road or rail (see Hayuth, 1981; Garnwa et al., 2009). This kind of trade was especially promoted for landlocked countries lacking their own ports. Thus the ‘dry port’ could offer a gateway role and reduce transport and administrative costs (Beresford and Dubey, 1991).

It was in the United States where true intermodal transport was established successfully. During the 1980s, carriers operating in the trans-Pacific trade were suffering from excess tonnage and low freight rates. To increase its cargo volumes, American President Lines (APL) formed the first transcontinental double-stack rail services, recognising that intermodal transport provided a 10-day time saving compared to the sea route through the Panama Canal to New York (Slack, 1990). While the transit time was important, APL also offered more services to the shipper, as the customer could receive a single through bill of lading. The growth of discretionary cargo allowed APL and other shipping lines to expand their capacity in the trans-Pacific. By using larger, faster ships, a carrier could offer a fixed, weekly sailing schedule, while the additional capacity reduced per-unit costs. In Europe, intermodal freight transport developed in the 1990s, although the fragmented geographical and operational setting (e.g. national jurisdictions and constraints on interoperability) as well as physical constraints (e.g. limited opportunities for double-stack operation) meant that progress was not as swift nor as successful as in the United States (Charlier and Ridolfi, 1994).

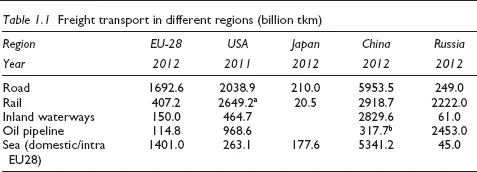

Different geographical regions have substantially different prerequisites for the respective mode of transport. There are, therefore, substantial differences between regions and countries when it comes to the usage of the different modes of transport (Table 1.1). Some of the differences can be explained by geographical conditions, but other important facts are regulatory aspects, status of infrastructure and, occasionally, technology.

Table 1.1Freight transport in different regions (billion tkm)

Source: Authors, based on European Commission, EU Transport in Figures: Statistical Pocketbook 2014, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2014.

aClass I rail.

bOil and gas pipelines.

From a transport work (tkm) perspective, EU-28 uses road transport extensively. Japan has a similar situation, but Japan’s geographical conditions make it more reliant on road transportation than the EU-28. The use of the double-stacking of containers, and hence more loading capacity, is one reason why the United States has a larger share of rail transport compared with the EU-28. Various types of electrical systems, signalling systems, and so on in the European Union (EU) are other reasons why rail has a lower market share in the EU compared with other regions.

SPATIAL CONCEPTS IN INTERMODAL TRANSPORT

While this book focuses mostly on the practical aspects of intermodal transport rather than abstract approaches, a brief overview of the geography of intermodal transport can be helpful for unde...