![]()

PART I

DIMENSIONS, HISTORY, AND GOALS

Chapter 1 The Dimensions of Multicultural Education

Chapter 2 Educating Citizens for Diversity in Global Times

Chapter 3 Multicultural Education: History, Development, Goals, and Approaches

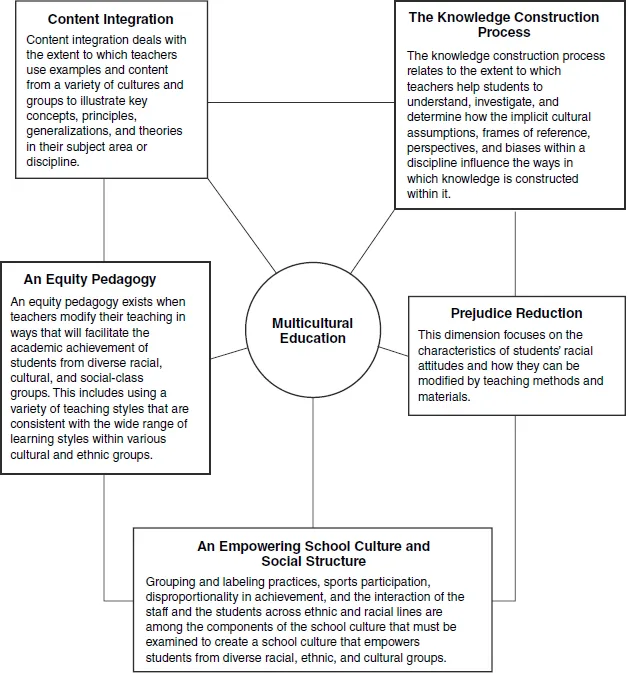

Chapter 1 describes five dimensions of multicultural education conceptualized by the author: (1) content integration, (2) the knowledge construction process, (3) prejudice reduction, (4) an equity pedagogy, and (5) an empowering school culture and social structure. The need for each of these dimensions to be implemented in order to create comprehensive and powerful multicultural educational practices is described and illustrated.

Chapter 2 describes how racial, ethnic, cultural, and language diversity is increasing in nation-states throughout the world because of worldwide immigration. It depicts how the deepening ethnic diversity within nation-states and the quest by different groups for cultural recognition and rights are challenging assimilationist notions of citizenship and forcing nation-states to construct new conceptions of citizenship and citizenship education. A delicate balance of unity and diversity should be an essential goal of citizenship education in multicultural nation-states, which should help students to develop thoughtful and clarified identifications with their cultural communities, nation-states, regions, and the global community. It should also enable them to acquire the knowledge, attitudes, and skills needed to act to make the nation and the world more democratic and just.

Chapter 3 describes the development of educational reform movements related to cultural and ethnic diversity within an historical context. Historical developments related to ethnicity since the early 1900s, the intergroup education movement of the 1940s and 1950s, new immigrants in the United States, and the ethnic revival movements that have emerged in various Western societies since the 1960s are discussed.

The historical development of multicultural education is also described in Chapter 3. The nature of multicultural education, its goals, current practices, problems, and promises are discussed. Four approaches to multicultural education are also described: the Contributions Approach, the Additive Approach, the Transformation Approach, and the Decision-Making and Social Action Approach.

THE DIMENSIONS OF MULTICULTURAL EDUCATION

THE AIMS AND GOALS OF MULTICULTURAL

EDUCATION

The heated discourse on multicultural education, especially in the popular press and among writers outside the field (BBC News, 2010, 2011; Chavez 2010), often obscures the theory, research, and consensus among multicultural education scholars and researchers about the nature, aims, and scope of the field (Banks, 2009b, 2012b). In highly publicized statements in 2010 and 2011, respectively, Angela Merkel, the chancellor of Germany, and David Cameron, the prime minister of the United Kingdom, stated that multiculturalism had failed in their countries. Several multicultural scholars in Germany and the United Kingdom stated that multiculturalism could not have failed in Germany and the United Kingdom because it has never been effectively implemented in policy or practice.

A major goal of multicultural education—as stated by specialists in the field—is to reform schools, colleges, and universities so that students from diverse racial, ethnic, and social-class groups will experience educational equality. The Routledge International Companion to Multicultural Education (Banks, 2009b) and the Encyclopedia of Diversity in Education, published in four volumes as well as electronically (Banks, 2012a), document the tremendous growth and development of theory, research, and practice in multicultural education within the last three decades.

Another important goal of multicultural education is to give both male and female students an equal chance to experience educational success and mobility (Klein, 2012). Multicultural education theorists are increasingly interested in how the interaction of race, class, and gender influences education (Grant & Zwier, 2012). However, the emphasis that different theorists give to each of these variables varies considerably. Although there is an emerging consensus about the aims and scope of multicultural education, the variety of typologies, conceptual schemes, and perspectives within the field reflects its emergent status and the fact that complete agreement about its aims and boundaries has not been attained (Nieto, 2009).

There is general agreement among most scholars and researchers in multicultural education that, for it to be implemented successfully, institutional changes must be made, including changes in the curriculum; the teaching materials; teaching and learning styles (Lee, 2007), the attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors of teachers and administrators; and the goals, norms, and culture of the school (Banks & Banks, 2004, 2013). However, many school and university practitioners have a limited conception of multicultural education; they view it primarily as curriculum reform that involves changing or restructuring the curriculum to include content about ethnic groups, women, students with disabilities, LGBT students, and other minoritized cultural groups. This conception of multicultural education is widespread because curriculum reform was the main focus when the movement first emerged in the 1960s and 1970s and because the multiculturalism discourse in the popular media has focused on curriculum reform and has largely ignored other dimensions and components of multicultural education (Chavez, 2010).

THE DIMENSIONS AND THEIR IMPORTANCE

If multicultural education is to become better understood and implemented in ways more consistent with theory, its various dimensions must be more clearly described, conceptualized, and researched (Banks, 2004). Multicultural education is conceptualized in this chapter as a field that consists of five dimensions I have formulated (Banks, 2012b):

1. Content integration,

2. The knowledge construction process,

3. Prejudice reduction,

4. An equity pedagogy, and

5. An empowering school culture and social structure (see Figure 1.1).

Each of the five dimensions is defined and illustrated later in this chapter.

Educators need to be able to identify, to differentiate, and to understand the meanings of each dimension of multicultural education. They also need to understand that multicultural education includes but is much more than content integration. Part of the controversy in multicultural education results from the fact that many writers in the popular press see it only as content integration and as an educational movement that benefits only people of color (Glazer, 1997). When multicultural education is conceptualized broadly, it becomes clear that it is for all students, and not just for low-income students and students of color (May, 2012). Research and practice will also improve if we more clearly delineate the boundaries and dimensions of multicultural education.

This chapter defines and describes each of the five dimensions of multicultural education. The knowledge construction process is discussed more extensively than the other four dimensions. The kind of knowledge that teachers examine and master will have a powerful influence on the teaching methods they create, on their interpretations of school knowledge, and on how they use student cultural knowledge. The knowledge construction process is fundamental in the implementation of multicultural education. It has implications for each of the other four dimensions—for example, for the construction of knowledge about pedagogy.

FIGURE 1.1 The Dimensions of Multicultural Education

LIMITATIONS AND INTERRELATIONSHIP

OF THE DIMENSIONS

The dimensions typology is an ideal-type conception. It approximates but does not describe reality in its total complexity. Like all classification schema, it has both strengths and limitations. Typologies are helpful conceptual tools because they provide a way to organize and make sense of complex and distinct data and observations. However, their categories are interrelated and overlapping, not mutually exclusive. Typologies rarely encompass the total universe of existing or future cases. Consequently, some cases can be described only by using several of the categories.

The dimensions typology provides a useful framework for categorizing and interpreting the extensive literature on cultural diversity, ethnicity, and education. However, the five dimensions are conceptually distinct but highly interrelated. Content integration, for example, describes any approach used to integrate content about racial and cultural groups into the curriculum. The knowledge construction process describes a method in which teachers help students to understand how knowledge is created and how it reflects the experiences of various ethnic, racial, cultural, and language groups.

THE MEANING OF MULTICULTURAL EDUCATION

TO TEACHERS

A widely held and discussed idea among theorists is that, in order for multicultural education to be effectively implemented within a school, changes must be made in the total school culture as well as within all subject areas, including mathematics (Nasir & Cobb, 2007) and science (Lee & Buxton, 2010). Despite the wide acceptance of this basic tenet by theorists, it confuses many teachers, especially those in subject areas such as science and mathematics. This confusion often takes the form of resistance to multicultural education. Many teachers have told me after a conference presentation on the characteristics and goals of multicultural education: “These ideas are fine for the social studies, but they have nothing to do with science or math. Science is science, regardless of the culture of the students.”

This statement can be interpreted in a variety of ways. However, one way of interpreting it is as a genuine be lief held by a teacher who is unaware of higher-level philosophical and epistemological knowledge and issues in science or mathematics or who does not believe that these issues are related to school teaching (Harding, 1998, 2012). The frequency with which I have encountered this belief in staff development conferences and workshops for teachers has convinced me that the meaning of multicultural education must be better contextualized in order for the concept to be more widely understood and accepted by teachers and other practitioners, especially in such subject areas as mathematics and science.

We need to better clarify the different dimensions of multicultural education and to help teachers see more clearly the implications of multicultural education for their own subject areas and teaching situations. The development of active, cooperative, and motivating teaching strategies that makes physics more interesting for students of color might be a more important goal for a physics teacher of a course in which few African American students are enrolling or successfully completing than is a search for ways to infuse African contributions to physics into the course. Of course, in the best possible world both goals would be attained. However, given the real world of the schools, we might experience more success in multicultural teaching if we set limited but essential goals for teachers, especially in the early phases of multicultural educational reform.

The development of a phase conceptualization for the implementation of multicultural educational reform would be useful. During the first or early phases, all teachers would be encouraged to determine ways in which they could adapt or modify their teaching for a multicultural population with diverse abilities, learning characteristics, and motivational styles. A second or later phase would focus on curriculum content integration. One phase would not end when another began. Rather, the goal would be to reach a phase in which all aspects of multicultural educational reform would be implemented simultaneously. In multicultural educational reform, the first focus is often on content integration rather than on knowledge construction or pedagogy. A content-integration focus often results in many mathematics and science teachers believing that multicultural education has little or no meaning for them. The remainder of this chapter describes the dimensions of multicultural education with the hope that this discussion will help teachers and other practitioners determine how they can implement multicultural education in powerful and effective ways.

CONTEXTUALIZING MULTICULTURAL EDUCATION

We need to do a better job of contextualizing the concept of multicultural education. When we tell practitioners that multicultural education implies reform in a discipline or subject area without specifying in detail the nature of that reform, we risk frustrating motivated and committed teachers because they do not have the knowledge and skill...