- 614 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

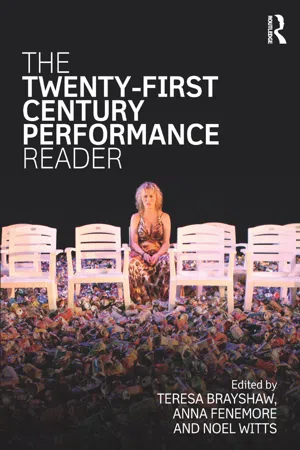

The Twenty-First Century Performance Reader

About this book

The Twenty-First Century Performance Reader combines extracts from over 70 international practitioners, companies, collectives and makers from the fields of Dance, Theatre, Music, Live and Performance Art, and Activism to form an essential sourcebook for students, researchers and practitioners.

This is the follow-on text from The Twentieth-Century Performance Reader, which has been the key introductory text to all kinds of performance for over 20 years since it was first published in 1996. Contributions from new and emerging practitioners are placed alongside those of long-established individual artists and companies, representing the work of this century's leading practitioners through the voices of over 140 individuals. The contributors in this volume reflect the diverse and eclectic culture of practices that now make up the expanded field of performance, and their stories, reflections and working processes collectively offer a snapshot of contemporary artistic concerns. Many of the pieces have been specially commissioned for this edition and comprise a range of written forms – scholarly, academic, creative, interviews, diary entries, autobiographical, polemical and visual.

Ideal for university students and instructors, this volume's structure and global span invites readers to compare and cross-reference significant approaches outside of the constraints and simplifications of genre, encouraging cross-disciplinary understandings. For those who engage with new, live and innovative approaches to performance and the interplay of radical ideas, The Twenty-First Century Performance Reader is invaluable.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Action Hero

- 1 -

Gemma, James and Action Hero

-2-

Who are you being?

- 3 -

Ethics

- 4 -

Collaboration as a dialogic process

- 5 -

Ideas in dialogue

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- In dialogue

- Teresa Brayshaw, Anna Fenemore and Noel WittsINTRODUCTION

- 1 Action Hero What’s Love Got to do with It? Gemma and James and Action Hero

- 2 Mohammad Aghebati Interview with Jessica Rizzo

- 3 Patricia Ariza Interview with Beatriz Cabur

- 4 Back to Back Theatre on Making Theatre

- 5 Brett Bailey Interview with Anton Krueger

- 6 Dalia Basiouny Performance Through the Egyptian Revolution: Stories from Tahrir

- 7 Jérôme Bel In Conversation with Catherine Wood

- 8 Blast Theory Ulrike and Eamon Compliant: Artists’ Statement

- 9 Tammy Brennan Confined: Storyboard

- 10 Tania Bruguera Interview with Jeannette Petrik

- 11 The Builders Association Marianne Weems in Conversation with Eleanor Bishop

- 12 Liu Chengrui A Selection of Actions: A Conversation with Pui Yin Tong

- 13 Padmini Chettur Some Thoughts for the Future

- 14 Constantin Chiriac Interview with Noel witts

- 15 David Chisholm The Memory of Remembering: Exomologesis and Exagoreusis in the Experiment

- 16 Clod Ensemble Performing Medicine

- 17 María José Contreras The Body of Memory: María José Contreras’ Performance Practices in the Chilean Transition

- 18 Augusto Corrieri A Conjuring Act in the Form of an Interview

- 19 Tim Crouch Interview with Seda Ilter

- 20 Dah Theatre Some Thoughts on the Quality of Attention

- 21 Tess de Quincey A Future Body

- 22 Derevo Endless Death Show

- 23 Dood Paard About Us

- 24 Every house has a door From One Meaning to Another

- 25 Eleonora Fabião Things that Must be Done Series

- 26 Oliver Frljić Interview With Suzana Marjanić

- 27 Gecko An Organic Journey

- 28 Getinthebackofthevan Making Things Worse

- 29 Gibson/Martelli The Fifth Wall

- 30 Gob Squad On Participation

- 31 Heiner Goebbels Aesthetics of Absence: How it All Began

- 32 Chris Goode The Cat Test

- 33 Shirotama Hitsujiya Interview with Naito Mao and Hibino Kei

- 34 Hotel Pro Forma Performance as an Investigation of the World

- 35 Wendy Houstoun Some Body and no Body: The Body of a Performer

- 36 Imitating the dog Theatricalising Cinema / Screening Theatre

- 37 Hiwa K Interview with Anthony Downey and Amal Khalaf

- 38 La Fura dels Baus Interview with Mercè Saumell

- 39 Lone Twin Greg Whelan: Interview with Carl Lavery and David Williams

- 40 Silvia Mercuriali Interview with Josephine Machon

- 41 Monster Truck But the Whores Always Loved Me

- 42 Needcompany Jan Lauwers: Interview with Noel Witts

- 43 New Art Club How We Set out to Make a Piece about Controversial Works of Art and Ended up Getting Naked and Talking about How We Feel about our Bodies

- 44 Oblivia Time Stopper

- 45 Toshiki Okada Interview with Jeremy Barker

- 46 Ontroerend Goed Personal Trilogy: The Smile off Your Face, Internal and a Game of You

- 47 Kira O’Reilly The Art of Kira O’Reilly

- 48 Mike Pearson Bubbling Tom

- 49 Michael Pinchbeck This is A Love Letter

- 50 Punchdrunk Felix Barrett: Interview with Josephine Machon

- 51 Silviu Purcărete Where are your Training Grounds?

- 52 Quarantine A Show of Hands

- 53 Reckless Sleepers “Middles” and “Physics”

- 54 Ridiculusmus A Chat about Comedy

- 55 Rimini Protokoll Interview with Peter M. Boenisch

- 56 Farah Saleh Interview with Marianna Liosi

- 57 Peter Sellars Interview with Bonnie Maranca

- 58 Shunt A Performance Collective

- 59 Agata Siniarska Do it to Me Like in a Real Movie: Lecture Performance

- 60 Deepan Sivaraman Interview with Noel Witts

- 61 Sleepwalk Collective Lost in the Funhouse, or All You Need to Make a Show is a Girl and a Microphone

- 62 Andy Smith this is it: Notes on a Dematerialised Theatre

- 63 Socìetas Raffaello Sanzio Entries from a Notebook of Romeo Castellucci

- 64 Junnosuke Tada Interview with Masashi Nomura

- 65 Third Angel Testing the Hypothesis

- 66 Ultima Vez Wim Vandekeybus: Interview with MichaËl Bellon

- 67 Unlimited Am I Dead Yet?

- 68 Sankar Venkateswaran Theatre of the Mind

- 69 Dries Verhoeven Interview with Robbert van Heuven

- 70 Vincent Dance Theatre Motherlands

- 71 Aaron Williamson Demonstrating the World: A Public Intervention Performance

- 72 Xing Xin Interview with Pui Yin Tong

- 73 Andriy Zholdak Theory / Lectures of Andriy Zholdak

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app