Learning about contemporary Southeast Asia can be a challenge because the region is no longer a primary focus of international attention. Weeks go by without any major news stories about countries that used to dominate the discussions of government officials and ordinary citizens. Because of the end of the Cold War, as well as events put in motion on September 11, 2001, international observers focus their attention on other parts of the world. Moreover, the lingering trauma, disillusionment, and cynicism associated with the Vietnam War have also kept many journalists, political scientists, and policymakers from focusing on Southeast Asia.

International news coverage of Southeast Asia today remains dominated by the superficial and sensational. Images of sunny beaches, soccer-playing elephants, and “exotic” cuisine are standard fare for both viral videos and reporters of the globalization era. When serious stories from the region manage to enter the global news cycle, the images are typically of tragedy, violence, and exploitation—of cyclone victims, bandanna-clad kidnappers, or underage workers in sweatshops. In-depth commentaries about Southeast Asia might center on the region’s transformation “from a battleground to a marketplace” or on problems of environmental degradation but, generally speaking, Southeast Asia’s story is persistently overshadowed by conflict in the Middle East, the movements of US troops, and the rise of China.1

Southeast Asia’s recent story is more complex than sensational headlines and stereotypical images suggest. In fact, as the world turns its attention elsewhere, the 650 million people who live in the region are experiencing unprecedented socioeconomic change. New forms of wealth and poverty are emerging across the region. Wrenching conflicts over rights, identity, social justice, and power have become the everyday experience of many Southeast Asians. Although it no longer draws the international attention it once did, perhaps no region in the world is more dynamic.

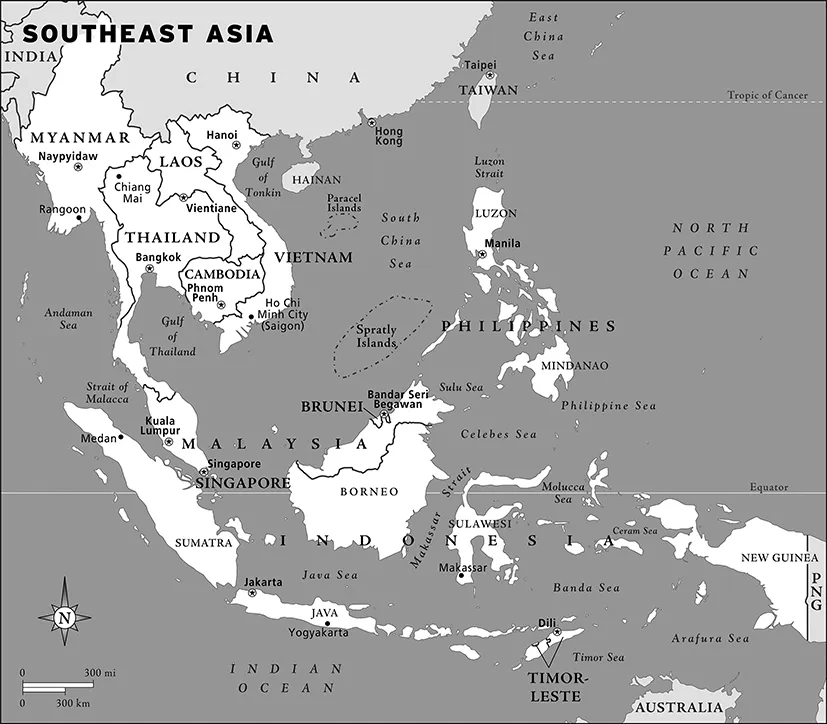

A new era in international relations has arisen in the past several decades with lasting repercussions for Southeast Asia. Political, economic, and social forces of unprecedented scope are currently transforming the entire region. Southeast Asia in the New International Era analyzes contemporary politics in the context of these new international and domestic realities from both Southeast Asian and international perspectives. This chapter introduces the region, describes changes accompanying the new international era, and explains how standard regime labels fall short in characterizing the richness and complexity of Southeast Asian politics. Eleven country chapters follow that evaluate each country in terms of basic political history, major institutions and social groups, state-society relations and democracy, economy and development, and foreign relations. Country chapters begin with Thailand, Myanmar (Burma), Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos—the countries of Peninsular Southeast Asia (sometimes referred to as “Mainland Southeast Asia”). The book continues with chapters on the Philippines, Indonesia, Timor-Leste, Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei—the countries of Insular Southeast Asia (sometimes referred to as “Maritime Southeast Asia”).2 A final chapter on the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) critically assesses regional integration and its future prospects. Readers interested in discussion regarding territorial claims in the South China Sea will find such embedded in individual country chapters, analysed purposefully from the varied perspectives of country claimants. The final chapter similarly examines the South China Sea dispute from an ASEAN organizational perspective.

Influences and Experiences

Southeast Asia, a region of remarkable diversity, consists of 11 countries with differing histories, cultural traditions, resource bases, and political-economic systems.3 Except for geographic proximity and a somewhat similar tropical environment and ecology, few characteristics link all these nations into a coherent whole. Nevertheless, before the international era arrived, a broad shape to a Southeast Asian political economy had developed from a few generalized influences, experiences, and social patterns described in this chapter. These influences and experiences include religious penetration by Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, and Christianity; colonialism and the introduction of political ideas from the West; the rise of nationalism associated with the struggle for independence; Japanese occupation; Cold War trauma; and regional economic transition. Shared social patterns, also outlined below, include a strong sense of the village as the primary unit of traditional identity; agricultural economies overtaken by urban-based manufacturing and service economies; and patron-client systems that influence sociopolitical interaction.

An important force shaping Southeast Asia from ancient to modern times has been the arrival and expansion of nonnative religions across the region. By supplanting local belief systems—or more often blending with them—exogenous religious influences evolved into today’s seemingly endogenous value systems, which contribute to the region’s diverse cultural milieu. Hinduism and Theravada Buddhism, arriving from South Asian sources, brought to the region Brahmanical notions of deva-raja (god-king); classical literature, such as the Ramayana and the Jataka tales; and karmic notions of rightful authority. Throughout the region, these cultural imports profoundly shaped the concept of power and the royal structures that wielded it. Mahayana Buddhism, brought from India via China, also influenced political ideals in the region, particularly in Vietnam. There, social order was believed to stem from hierarchal (Confucian) relations, Buddhist cosmology, and (Taoist) naturalism. Centuries of overseas Chinese migration also spread the influence of Chinese religion and folk beliefs throughout the region, especially in urban areas where migrant communities established themselves.

Subsequent to Hinduism and Buddhism, Islam arrived from merchants and traders from South Asia. Islam did not enjoy a wide presence in Southeast Asia until the fifteenth century, about the time Europeans first began to arrive with Christian traditions. Islam spread throughout insular Southeast Asia from island to island and then from coastal ports to interior settlements. Christianity did not spread deep roots in the region, except for in the predominantly Iberian-Catholic colonies of the Philippines and East Timor, as well as among some enduring communities in Vietnam and Indonesia. Over the centuries of religious interaction, the eclectic, religio-royal traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism have sometimes clashed with the universalist, law-based religions of Islam and Christianity. However, tolerance and syncretism rather than conflict characterizes most of Southeast Asia’s history of religious practice. Taken together, the diverse practices and beliefs of these religions, and their interactions, generate an array of cultural claims on how to organize societies politically and economically across the region.

Adding yet more complexity to this milieu of beliefs and practices was the gradual penetration of Western ideas of modernity, including “civilization,” nationalism, capitalism, republicanism, democracy, and communism. Most of these foreign notions and ideologies emerged in the region during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, that is, during the latest phase of nearly five centuries of European influence in the region. Many of the problems of political and economic development facing Southeast Asian leaders today can be traced to colonialism.4 The grand strategic games of imperial competition and colonial rule brought the formation of internationally recognized boundaries. These new “states” replaced the region’s nonintegrated dynastic principalities that only loosely governed rural populations and upland minority groups. Foreign attempts to integrate these disparate populations often proved difficult. The imperialists eventually guaranteed new boundaries and imposed a Western sense of geographic and political order on the region.5

By the late nineteenth century, national boundaries had been demarcated and the entire area of Southeast Asia was in European hands except Thailand, which ceded much territory to remain independent. Over time, a money economy was introduced and resource extraction created large-scale industries that required skilled and unskilled laborers. Because the rural populations of Southeast Asia found industrial labor antithetical to traditional values, the colonialists imported Chinese and Indians to work in factories, tin mines, and rubber plantations. The Chinese and Indian communities were often employed as a buffer between Europeans and local populations. In many cases, laws prevented the immigrants from owning agricultural land and pushed them into the commercial sector. Urban life in colonial Southeast Asia was, in many respects, more Chinese and Indian than local or European. A discernible immigrant communalism evolved in tandem with urbanization. Hindu, Confucian, and European influences affected trade, urban architecture, art, as well as societal tastes and norms. From the nineteenth century forward, overseas communities (the Chinese in particular) enjoyed economic power in Southeast Asia disproportionate to their numbers.

Among other changes, European colonists were responsible for the growth of the region’s first economic infrastructure of modern ports, railways, and roads. Although they staffed their bureaucracies with local elites, offering education to the most gifted, the colonists failed to develop institutions of accountable governance. Serving European rather than local interests, imperial administrators exploited natural resources for export and introduced new industries and economies related to mercantilist trade in tin, rubber, tapioca, opium, spices, tea, and other valued commodities. As they extracted from mines and expanded plantations, European governors wholly neglected local socioeconomic development. Over time the cruelty, exploitation, and injustice of colonial rule bred popular resentment and put into motion a new force in the region: nationalism.

The rise of anti-imperial nationalism was the most consequential product of colonialism in Southeast Asia. Although deliberate movements against European control punctuated the entire colonial history of Southeast Asia, it was the ideological battles of the twentieth century that fed the transformative nationalism that came to define the region’s future.

A traumatic experience under Japanese occupation during World War II further fueled aspirations for self-rule and independence across the region. Following Japan’s surrender in 1945 to Allied forces, Europe’s postwar leaders disregarded attempts by Southeast Asian leaders to declare formal independence. Eager for resources to rebuild their own war-torn economies, the colonists audaciously returned to extend control over their previously held territories: the British in Burma and Malaya; the French in Indochina (Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos); the Dutch in Indonesia; and the Portuguese in East Timor. To legitimize their ambitions, European administrators received international recognition for their actions through postwar treaties that excluded Southeast Asians from negotiations. In 1946, the Philippines, vacated by its American occupiers of forty-seven years, joined Thailand as one of the two independent Southeast Asian countries in the early postwar period.

Resolve for independence hardened. In Burma, Indonesia, and Vietnam, nationalism became an especially potent and unifying force that led to fierce struggles for self-determination. In Malaysia and Singapore, the struggle for merdeka (independence) was less violent but every bit as formative in cultivating a new sense of nationalist purpose. Across the region, experiences with colonialism differed but the nationalist rhetoric for genuine self-governance emerged as a political lingua franca among anticolonial revolutionaries. Thailand, having escaped direct colonial rule, attempted to construct its own sense of nationhood. Hoping to bind the various peoples within the borders of its constitutional monarchy, modernizing Thai elites suppressed local identities and cultivated a nationalist creed, “Nation, Religion, King.”

Relentless anti-imperial political activity and painfully violent episodes of conflict with colonial forces gradually produced two significant consequences for the region: the overdue withdrawal of the Europeans and the rise of a handful of charismatic, larger-than-life independence leaders, including Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam, Sukarno in Indonesia, Aung San in Burma, Tungku Abdul Rahman in Malaysia, and Prince Sihanouk in Cambodia. But even as decolonization and courageous independence leaders offered fresh hopes under sovereign statehood, a new dimension of geopolitical struggle, the Cold War, enveloped the region.

For Southeast Asians, the ironically named Cold War thoroughly destabilized the region with occupation, warfare, and even genocide. From 1945 to 1989, the effects of superpower politics led to the deaths of more than 10 million soldiers and civilians in the region. Countless bombs and bullets from conventional warfare and unimaginable atrocities caused by zealous ideologues and murderous despots, not to mention the appalling use of chemical defoliants by US forces, produced long-term tragedy for many Southeast Asians. The political and economic chaos of the Cold War not only delayed the independence of Southeast Asian states but also retarded their early development by politically dividing societies, peoples, and communities.

The Cold War was fought in Southeast Asia along three interrelated dimensions: internal ideological struggle, superpower rivalry, and interstate conflict. Leftist movements embracing communist visions for state control existed in every major Southeast Asian country during this period. In theory, competing ideological visions pit communism against democratic capitalism. But because the latter scarcely existed in the region, the primary foes of communist movements were right-leaning militaries, traditional monarchists, and neo-imperial foreign forces. US-USSR superpower rivalry, expressed most clearly in the Vietnam War, was also affected by the 1960 Sino-Soviet split over global communist supremacy. Ever in search of international patrons, Southeast Asian communists exploited this split to suit their largely nationalist purposes.

The meddling of three external Cold War powers in the region exacerbated existing conflicts and created new tensions. The most tragic conflict resulted in the rise of the genocidal Khmer Rouge, who, before the illegal US bombing of Cambodia, had demonstrated insufficient capacity to seize Cambodian state power. China, which had supported Vietnamese revolutionaries against both the French and the Americans, turned on its former communist ally in the mid-1970s. In an attempt to outmaneuver the Soviets, who maintained support for Vietnam, the Chinese backed the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. China’s communist leaders count among the very few diplomatic supporters of Cambodia’s Pol Pot clique, which is responsible for the deaths of 1.7 million Cambodians during its three-year reign of terror.

Superpower rivalry insidiously politicized ethnic relations throughout Southeast Asia as well. During the Cold War, both communist and noncommunist governments engaged in shocking anti-Chinese vio...