- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Now in an updated third edition, this best-selling textbook introduces primary teachers to the key issues in how to teach reading. The authors celebrate reading as an important, exhilarating part of the curriculum with the potential to transform lives, whilst also giving a balanced handling of contentious issues. Strongly rooted in classroom practi

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reading Under Control by Judith Graham,Alison Kelly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Didattica & Istruzione elementare. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

DidatticaSubtopic

Istruzione elementareChapter 1

How We Got to Where We Are

INTRODUCTION

There has never been a shortage of books about the teaching of reading. There have always been discussions and debates about how children learn to read and the best way to teach them. These debates are often passionate and polarised, sometimes even vitriolic. The difficulty is that there is no one definitive all-encompassing theory or method, so one of the things all teachers of reading have to do in order to feel in control is to inform themselves. Teachers need to have a balanced, historical perspective on the issues so that their developing understanding of the theories can inform practice.

This book is written at a time of significant change in the educational landscape, and governmental control of the teaching of reading has never been tighter. The year 1988 saw the publication of the first version of the National Curriculum (NC) that laid down the content of the English curriculum. Ten years later (1998), in a drive to raise standards, the National Literacy Strategy (NLS) expanded on this content and prescribed its delivery via a daily literacy hour. However, despite almost 15 per cent more pupils achieving the target level in reading expected at the end of Key Stage 2 (KS2) (level 4 in the NC) by 2005, there were still 95,000 children not reaching this level. Former Deputy Chief Inspector of Schools Jim Rose was commissioned to review the teaching of early reading. His report – the Independent Review of the Teaching of Early Reading (DfES, 2006a, the Rose Report) – is controversial in that it is tightly (some would say narrowly) prescriptive about the type of phonics teaching that should go on. However, it also endorses the importance of a very rich learning environment in which to embed such teaching.

This chapter offers a foundation for you to develop your understanding of reading: controversies about the subject relate to beliefs about what reading is, what it is that readers have to do, how reading is to be taught and the books that should be used. As we shall show, these beliefs are tied up with understandings about the nature of literacy and about how children learn; these understandings have changed across the years. In this chapter we will map out some of these changes.

LITERACY

Any discussion about reading has to be located in our understanding of what literacy is. At a tangible level, the tools of reading and writing have been transformed and have multiplied, so that the days of slates, chalk and quill pens have been superseded by screens and hundreds of different writing implements to choose from. Reading from the page is still the norm but consider the range of reading you do away from the page in any one day. You read from print in the environment; you may read emails from your computer screen, text messages from your mobile, information from the internet … the list is endless. And it is not just text-based print that you engage with; think of the many symbols, logos and other visual representations with which you are surrounded and which you ‘read’ and interpret continuously.

Charting the evolution of the tools of literacy is not so hard; what is much more complex is getting hold of what is actually meant by ‘literacy’. For many years this was unproblematic. The recitation of passages and rote learning that characterised classrooms of the late nineteenth century was underpinned by a narrow concept of literacy, and teachers were judged (and offered payment accordingly) if they taught in this restricted way. In the 1950s a definition from the Ministry of Education stated that being literate means someone is ‘able to read and write for practical purposes of daily life’ (in DES, 1975:10). A little later, UNESCO offered the following definition: ‘A person is literate who can, with understanding, both read and write a short simple sentence on his everyday life’ (in DES, 1975:10).

However, the ethnographer Brian Street (1997) argues that definitions like these are unsatisfactory, restricting and over-simplified. They assume that literacy is a set of skills and attributes that are transparent, universal and assessable. Wherever you are, literacy is straightforward and static. Because such definitions stand alone and are independent of particular cultural or social settings, Street calls this view of literacy an ‘autonomous’ one. He prefers to see literacy from an ‘ideological’ viewpoint – one that acknowledges social and cultural dimensions and refuses to separate literacy events from the prevailing set of beliefs and values of the culture from which they spring.

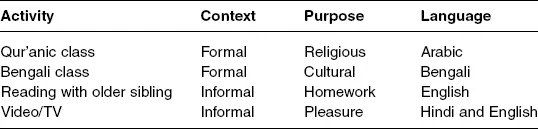

This ideological perspective is powerfully illustrated in a fascinating study (Gregory and Williams, 2000) of different generations of children growing up in the Spitalfields area of London. One of the groups that they worked with comprised Bangladeshi–British children. The table below shows the early out-of-school literacy-related experiences these children were having. Note the different languages with which these children were operating – Arabic, Bengali, English and Hindi – and then how wide-ranging the purposes for using these languages were – from formal religious learning about the Qur’an to informal watching of television. This description of the children’s literacies, which includes oral language, sits comfortably within Street’s ideologically based model of literacy.

An ideological perspective on literacy suggests that there is more than one literacy and challenges assumptions that lie behind words like ‘illiteracy’. Teachers working with the Travellers’ community in London in the 1980s found families often living in the restricted space offered by just one trailer and with none of the traditional trappings of literacy apparent – to all intents and purposes they were ‘illiterate’. However, oral storytelling was a strong part of these children’s lives and they were at ease with road signs and other environmental print: literacy for these children was different from those of their counterparts in school. Skilful teachers will recognise and build on children’s early, socially learnt experiences of literacy and in Chapter 4 we look more closely at these early, socially embedded experiences.

Table 1.1 Out-of-school literacy-related experiences of a group of Bangladeshi–British children (adapted from Gregory and Williams, 2000:168)

WHAT IS READING?

In formulating the principles that underpin the NC, Brian Cox, chair of the working party, offered the following definition of reading. It is one that still holds good today:

Reading is much more than the decoding of black marks upon a page; it is a quest for meaning and one which requires the reader to be an active participant.

(Cox, 1991:133)

There are three key ideas here. First of all, reading is quite clearly about decoding. In order to get at the printed word the reader has to crack the code needed to decipher the print. But, as reading a piece of nonsense text, or decoding a text in a language you do not understand, would show, there is much more to it than this. Reading is about making sense and the drive to make sense is what powers young children’s learning. As our discussion of literacy showed, making sense is, to a certain extent, culturally shaped and we need to hold firmly on to our understanding of children’s social and cultural identities. Finally, Cox’s definition includes the notion of active participation. Theories about children’s learning show them to be active constructors of meaning. So, reading is the bringing together of a text to be decoded and understood and a reader who has to engage actively with both these processes. How the reader does this has been the source of debate and research for many years.

MODELS OF READING

Approaches to the teaching of reading are determined by prevailing understandings about the reading process: the beliefs that educators hold (about how readers manage to turn the black marks into meaningful text) are what govern approaches. Over the years different models and frameworks have been offered to explain this complex cognitive process.

One-dimensional model

Until the twentieth century the view was that reading was a simple matter of decoding the black marks and was therefore just about seeing and hearing sounds and words. The neglect of meaning in this enterprise is brought sharply home when we read in Annual Reports of 1866 that inspectors asked pupils to read backwards from their reading primers in order to be sure that they had not memorised the texts in advance of the tests (Rapple, 1994). It follows logically from such a view that reading can be easily taught through the graded introduction of sounds and words. It is a model that accords with the pedagogy of the Victorian classroom, in which rote learning of sounds and words was the norm.

Orchestration models

In the twentieth century a broader view of reading developed and this can be illustrated through what we can call ‘orchestration’ models. The idea of orchestration comes from Bussis et al., who propose that ‘reading is the act of orchestrating diverse knowledge’ (1985:40).

The first and most famous of these models is one in which different cue-systems are orchestrated. It was developed during the 1970s and 1980s by psycholinguist Kenneth Goodman (1982), who, along with other researchers (e.g. Frank Smith, 1978), brought together the disciplines of psychology and linguistics. This led to a broader view of reading than had been seen before: whilst words and letters were still important, the model now included other information that children bring to reading. This model shows what children need to draw on and pull together when they read.

This ‘other information’ is contained in three cue-systems. The first of these is the semantic cue-system, in which readers draw on meaning from the text itself but also from what they know of the situation they are reading about, from life experience and from other texts. A child who knows that ‘ice creams melt in the sun’ is unlikely to miscue and read that ‘ice creams meet in the sun’. Next – and it is important to note that these are not staged – is the syntactic cue-system in which readers draw on what they know of language and grammar (spoken and written) to predict what is coming next. A child who knows that what ice creams do in the sun is melt is unlikely to miscue and read that ‘ice creams meal in the sun’, as she implicitly knows that a verb needs to fill that slot. The third cue-system is grapho-phonic in which readers use what they know of sound–symbol correspondences, visual knowledge of letter combinations and sight vocabulary. Thus, a child meeting ‘melt’ for the first time could blend its four constituent phonemes together: ‘m’ - ‘e’ - ‘l’ - ‘t’.

Unlike the one-dimensional model or the cognitive psychological ones that are discussed below, psycholinguists assumed that ‘there was only one reading process, that is that all readers, whether beginner/inexperienced or fluent/experienced use the same process, although they differ in the control they have over the process. They assumed a non-stage reading process’ (Hall, 2003:40).

More recently, the NLS adapted this theoretical model to a teaching model which depicted reading as a process of shedding light on the text by means of a range of ‘searchlights’. With four searchlights mapping directly on to the cue-systems (graphic and phonic cues were split into two) this model governed the teaching of reading from 1998 to 2006. Teaching objectives for reading were split into levels which covered the searchlights. The three levels were text, sentence and word: at text level, the focus was on meaning and context, at sentence level on grammar and at word level on phonics and graphic knowledge.

Cognitive psychological views

Models that draw on multi-level orchestration were challenged by critics. Drawing from cognitive psychology, these critics argued that such models reflect what it is that skilled, rather than beginner, readers do. They believed that the importance of phonic strategies in the early stages of reading was marginalised. A cognitive psychological stance (e.g. Frith, 1985; Ehri, 1987) sees learning to read as a staged, linear process with decoding as the first step.

The difference between these models and the one-dimensional model is that they take account of comprehension as well as decoding. However, the emphasis is different from that of the psycholinguists. For psycholinguists, meaning is privileged as the primary driver and such a model is often described as offering a ‘top-down’ teaching approach. Cognitive psychologists on the other hand place the emphasis on word recognition, thus offering the reverse – a ‘bottom-up’ approach. As Hall so aptly puts it: ‘both schools of thought … agree on the destination … but disagree on the journey to that destination’ (Hall, 2003:69).

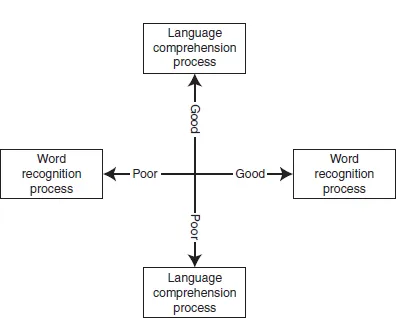

The Rose Report recommended that the NLS searchlight model be replaced with a framework drawn from cognitive psychology – the ‘simple view of reading’ – and this has been adopted by the Primary National Strategy (PNS) (DfES, 2006b). The ‘simple view’ makes a clear distinction between beginning reading (learning to read) and the longer process of ‘reading to learn’. In contrast to orchestration models, the ‘simple’ model views learning to read as starting with an early short, focused delivery of phonics teaching, which then gives way to lifelong work on comprehension: ‘Obviously, in order to comprehend written texts children must first learn to recognise, that is decode, the words on the page’ (DfES, 2006a:53). The simple view is represented as shown in Figure 1.1.

You will see that two different sets of processes are identified here: word recognition processes, which focus on decoding, and language comprehension processes, which are about understanding texts and spoken language. The model shows four quadrants into which children may fall. For instance, a child with weak decoding skills but strengths in understanding and interpreting texts could be positioned in the top left quadrant, thus helping the teacher determine what kind of support she needs next. It is highly likely that progress in these dimensions will be uneven and teachers will need to monitor children’s learning needs closely in relation to both sets of processes. It is important to note that the Rose Report makes it clear that this model of reading needs to be ‘securely embedded within a broad and language-rich curriculum’ (DfES, 2006a:16) and that oral development is emphasised as key to underpinning progress in both word recognition and language comprehension.

Figure 1.1 The simple view of reading (DfES, 2006a:77)

At this stage you might find it useful to pause and consider these different models of how we learn to become readers. There is a diagram for the simple view – could you devise one for the other perspectives? Try listing the similarities and differences between the models. What arguments could you put for and against each of them? The simple view is the model that is meant to be implemented in schools but are there insights from the other models that you will find useful to remember?

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

With different models of reading come different kinds of reading lessons. The following section offers a brief historical overview of approaches to the teaching of reading. You might find it helpful to consider where you, your parents or your grandparents fit into this history, so, before you read any further, spend five minutes jotting down anything at all that you remember about learning to read either at school or home: a book maybe, or a significant memory of reading with another adult. Whether you learnt to read in Britain or another country, you may find that you remember texts that are described or ones that were similar to them, or maybe there are teaching approaches mentioned here that chime with your own memories.

The alphabetic method

As the section about one-dimensional models described, for many years people thought that reading was simply about seeing and hearing letters, sounds and words. This view leads to a particular kind of teaching where reading can be broken down into little bits to be taught in sequence. An early example was the ‘alphabetic method’ that was used in England from medieval times. In this approach, the very few children who had reading lessons learnt the names of the letters of the alphabet and spelled out combinations of them. In museums, there are examples of seventeenth-century horn books, so called because they were constructed out of wood with a sheet of paper protected by a layer of transparent horn. These early reading books were not much bigger than a child’s hand and could be tied on to the child’s belt so that they did not get lost. They usually comprised the alphabet, the Lord’s Prayer (which was of course a very well...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Notes on contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 How We Got to Where We Are

- 2 Reading Differences, Reading Diversity

- 3 Getting to Grips with Phonics

- 4 The Reading Journey

- 5 Reading Routines

- 6 Reading Resources

- 7 Monitoring and Assessing Reading

- 8 Meeting Individual Needs

- 9 Dyslexia and Reading

- References

- Author index

- Subject index