- 78 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Persistent skills shortages have constrained new investments and economic growth in Sri Lanka. This study assesses the skills deficit in two priority sectors—food and beverages, and electronics and electricals. It recommends supply-side responses to increase the quantity and quality of labor in these areas. The recommendations include raising awareness among young people about the sectors' employment potential, upgrading courses, providing professional development for instructors, and establishing collaborations between businesses and training institutes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Skills Gaps in Two Manufacturing Subsectors in Sri Lanka by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Skills. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Rationale and Objectives

Although Sri Lanka was the first country in South Asia to liberalize its economy and emphasize export-led growth in its policy framework, objectives of structural transformation and export diversification have been met only partially over the last 4 decades. While the nearly 30-year civil conflict acted as a constraint during much of the period, the decade following the end of the conflict saw little change in the country’s export portfolio. Exports, as a share of gross domestic product (GDP), fell from 33.3% in 2000 to 12.5% in 2016 before increasing slightly to 13.4% in 2018. Government expenditure on infrastructure became the main impetus for economic growth (Weerakoon, Kumar, and Dime 2019; World Bank 2019). Meanwhile, the incidence of poverty declined and real wages rose, especially among the low-skilled, which may have been partly due to demographic change and the tightening labor market rather than any appreciable increase in productivity growth (Chandrasiri, De Mel, and Jayathunge 2017). Nearly two-thirds of Sri Lanka’s employed labor force still work under informal conditions with the pace of informal job growth far outstripping job creation in formal employment (Majid and Gunatilaka 2017).

Sri Lanka has not been able to fully realize its potential in export-led growth for many reasons. These include access to land, skills gap, restrictive product market regulations, inward-oriented trade policies which created an “anti-export” bias, a weak business climate, and complex tax regime prior to enactment of the new Inland Revenue Act in April 2018. Athukorala et al. (2017), Center for International Development (2018), and World Bank (2015) are some of the studies that discuss the constraints on Sri Lanka’s growth prospects. Many institutional factors also constrain growth, several relating to the country’s political economy. Key among them is the lack of necessary institutional and policy support to generate the skills essential to upgrade and diversify the economy’s production and export bases. To generate sources of sustained foreign exchange earnings, major structural reforms are needed, particularly those that prioritize export-led growth and diversification. These reforms would include structurally transforming Sri Lanka’s human capital in line with technologically driven market demand. While Sri Lanka’s demographic window has ended and its population is aging, the postwar baby boom (de Silva and de Silva 2015) may provide a narrow window of opportunity over the next decade to accelerate economic growth and incomes, so long as young workers entering the labor force have the skills to engage in productive work.

In line with informing the formulation of appropriate skills development policies, this study uses the most recently available sample survey and administrative data to assess skills gaps in two manufacturing subsectors that have the potential for export-led growth and capacity for high levels of labor absorption. The subsectors were selected according to a series of criteria described in Chapter 2. The selection process found the food and beverages, and electronics and electricals subsectors as needing to be prioritized for targeted skills development. The next section describes the data and methods used for the analysis.

1.2 Data and Methods

Definition of skills

The present study is industry specific. Hence, the assessment of skills gaps is based on core competencies and technical skills. Core competencies help in the development of core products and enhance the competitiveness of a firm. In broad terms, they comprise a set of human skills acquired via teaching, reading, or interaction with others in real life. Core competencies, behaviors, and attributes enable a person to function in the workplace. While different terms are used in different countries to define them, these skills typically include communication skills, problem-solving, computer literacy, teamwork, and time management.1 In training programs, such skills are usually imparted as modules and are assessed. The common core competency skills include communication, problem-solving, integrity, stability, interpersonal skills, extroversion, and openness. However, effective application of these skills is not only conditioned by training in them but also by the presence of appropriate personality traits, behaviors, and attitudes in a workplace.

Technical skills are used to describe occupation-specific competencies which demonstrate proficiency or mastery over technical know-how and their application to given work assignments/processes.2 Technical skills are the abilities and knowledge needed to perform specific tasks. They are practical, and often relate to mechanical processes, information technology, mathematical operations, or scientific tasks. They are more job-specific than core competencies and are measured in terms of technology use, computer use, mechanical use, machinery use, English language ability, the ability to work autonomously, and manual labor skills. Technical skills are acquired through learning, training, and on-the-job training (OJT). This approach of skills gap assessment is consistent with the technical and vocational education and training (TVET) sector skills development programs.

Data and methods

Skills gaps are the shortfall of supply over demand and, in this study, skills gaps are estimated by first estimating the demand for skills, and then their supply, and thereafter matching the two. Due to lack of a longitudinal data set with information on the factors conditioning labor demand necessary to estimate a model of skills demand or supply, information from a variety of sources is collated. To estimate demand, data from the Labour Demand Survey of 2017, Quarterly Labour Force Surveys of 2016, and the Annual Survey of Industries 2011–2015 of the Sri Lanka Department of Census and Statistics (DCS) as well as 2012 data from the Skills Toward Employment and Productivity (STEP) initiative of the World Bank are used. To estimate supply, administrative data from training providers, particularly the Tertiary and Vocational Education Commission (TVEC) and affiliated institutes, are used. The analysis is also informed by qualitative data gathered from consultations with stakeholders, that is, employers and training providers, and analyzed in the context of skills supply and skills gaps.

The methodological approach consisted of several steps. First, growth employment elasticities are estimated using data from the DCS Annual Survey of Industries 2011–2015 and baseline employment figures by occupation from the DCS Labour Demand Survey of 2017, to project the demand for labor by occupation from 2019 to 2025 (Chapter 3). Additionally, the chapter also estimates deficits in core competencies and technical skills using the World Bank’s STEP data and the DCS Quarterly Labour Force Survey of 2016. In Chapter 4, administrative data on recent actual intake figures and dropout figures in TVET and higher educational institutes are used to estimate expected output of graduates over the period 2019–2025 which are then matched with the labor demand projections to estimate skills gaps.

The next chapter provides extensive information about the background of the study, beginning with an overview of Sri Lanka’s labor market and an assessment of the skills-generating capacity and performance of the general education and TVET sectors. This is followed by an account of the criteria used to select the two manufacturing subsectors for the skills gaps analysis and a review of the skills-related characteristics of the two subsectors. Chapter 3 focuses on estimating the demand for skills in the two subsectors, while Chapter 4 looks at supply and estimates the skills gaps. Chapter 5 concludes with an overview of the findings and detailed recommendations for policy action.

CHAPTER 2

BACKGROUND

2.1 Overview of Sri Lanka’s Labor Market

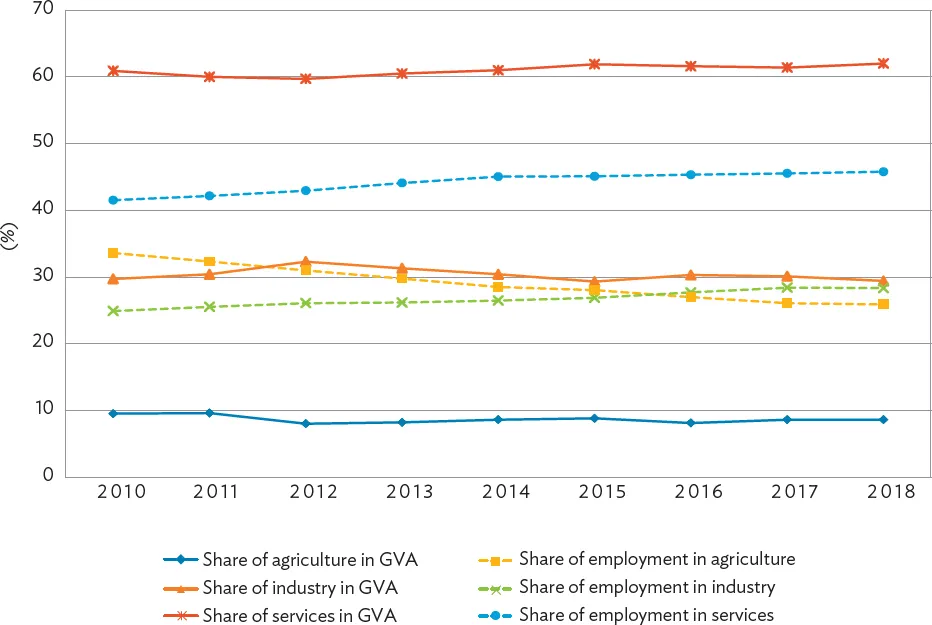

Sri Lanka posted a relatively respectable average growth rate of 5.6% from 2010 to 2018, but has had only limited change in the structural composition of output (Figure 2.1). Agriculture’s contribution to gross value added (at basic prices), at 9.5% in 2010, declined to 8.6% in 2018, while the industry sector’s contribution has remained stable, at 29.7% in 2010 and 29.4% 2018. In contrast, the contribution to gross value added of Sri Lanka’s services sector increased marginally from 60.9% in 2010 to 62.0% in 2018. The structure of employment has changed more noticeably, but not dramatically. For example, over the same period, the employment share of the services sector rose from 40% to 45%, the share of agriculture declined from 34% to 26%, and the share of the industry sector inched up from 26% to 28%. The following sections take a closer look at the characteristics of Sri Lanka’s labor market.

Figure 2.1: Trends in the Structure of Output and Employment in Sri Lanka, 2010–2018

GVA = gross value added.

Sources: Central Bank of Sri Lanka. Annual Reports (various years); and World Bank. World Development Indicators (accessed 14 October 2018).

Demographic transition and participation

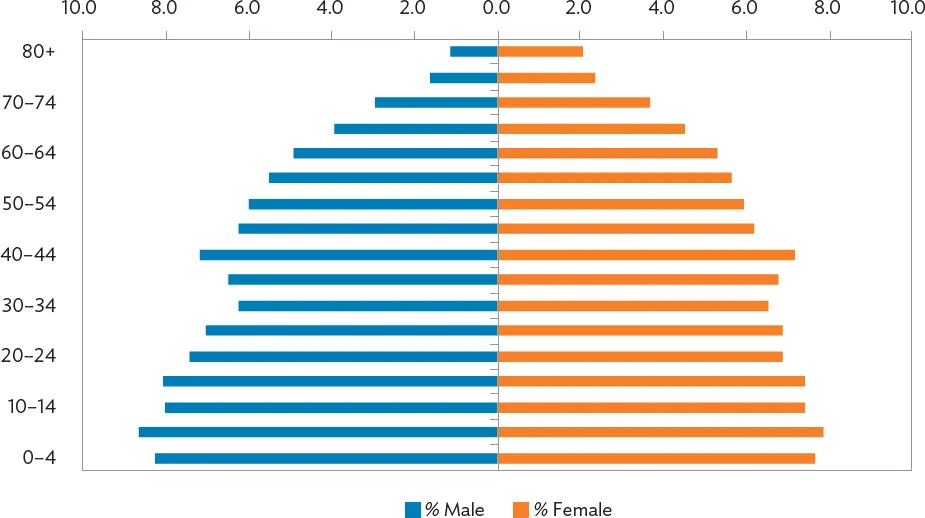

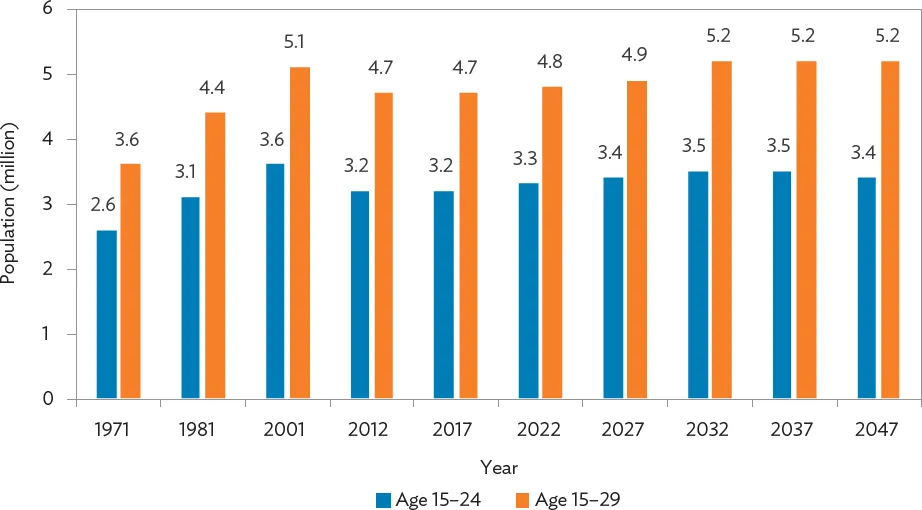

Sri Lanka’s population has been rapidly aging with share of working-age population in total population declining (Figure 2.2) and the absolute number of working-age population projected to decline after 2027 based on United Nations population projections. However, since fertility rates increased after the civil conflict ended in 2009, a “youth bulge” is likely to emerge as the youth population (15–29 years old) is expected to increase (Figure 2.3) (de Silva and de Silva 2015). However, this bulge may not be enough to stem the decline in working-age population. Yet it does provide Sri Lanka another chance at stimulating growth if, over the next 10 years, the correct mix of policies is put in place. Foremost among them are policies and programs to forge a highly educated and skilled workforce, facilitate technology transfer, improve the investment climate, and provide institutional and other supportive systems (de Silva and de Silva 2015). This would require a paradigm shift in the generation of skills and concerted efforts at reducing the skills gap.

Figure 2.2: Share of Elderly and Working-Age Population in Total Population, 2015

Note: Working-age population comprise those in the age group 15–59 years, while the elderly are those aged 60 years and above.

Source: de Silva and de Silva (2015).

Figure 2.3: Sri Lanka’s Youth Population, 1971–2047

Note: Data for 2017–2047 are based on population projection by de Silva and de Silva (2015).

Source: de Silva and de Silva (2015).

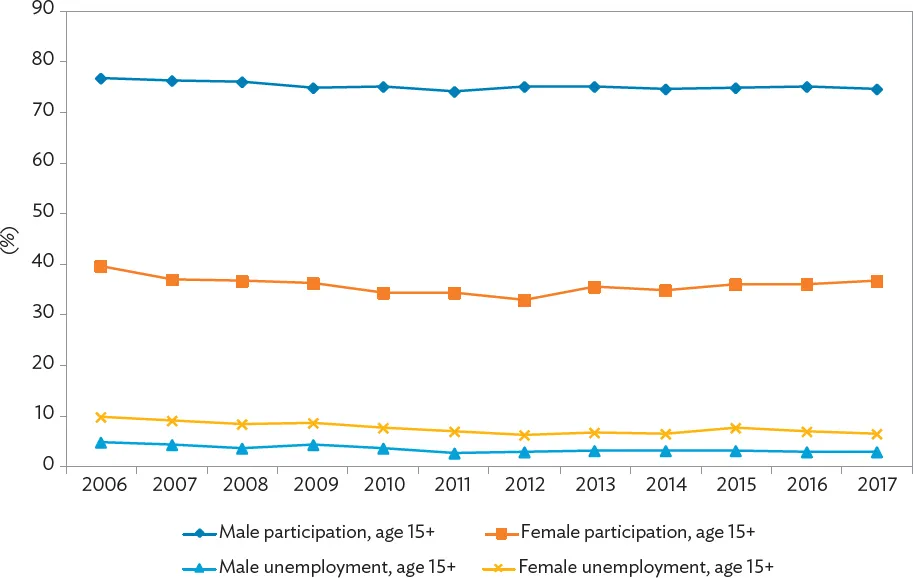

Meanwhile, as Sri Lanka’s population ages, its labor market is becoming tight. The male participation rate remains high and is unlikely to increase further, while the female labor force participation rate continues to remain low as women appear unwilling or unable to engage in paid work (Figure 2.4). While women’s participation rate has been low and stable, there were some variations by sector over the longer period, from 1996 to 2016 (Figure 2.5). Participation rates have been, historically, highest in the estates sector, though these show a long-term decline. Women in rural areas have marginally increased their participation, but urban women hardly at all. While labor force participation rates at the national level have been remarkably stable, unemployment rates have declined (Figure 2.4). The decline in the unemployment rate and a rise in the employment-to-population ratio underlie the stability in participation.

Figure 2.4: Trends in Labor Force Participation and Unemployment in Sri Lanka by Gender, 2006–2017

Notes: Data for 2009 onward include all districts. Data for previous years either excluded both Northern Province and Eastern Province, Northern Province only, or some districts of Northern Province. For details, ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Tables and Figures

- Preface

- Abbreviations and Currency Equivalents

- Executive Summary

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Background

- Chapter 3: Demand for Skills

- Chapter 4: The Supply of Skills and Skills Gaps in the Food and Beverages, and Electronics, and Electricals Subsectors

- Chapter 5: Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

- Appendix

- References

- Footnotes

- Back Cover