- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Comic Art in Museums

About this book

Contributions by Kenneth Baker, Jaqueline Berndt, Albert Boime, John Carlin, Benoit Crucifix, David Deitcher, Michael Dooley, Damian Duffy, M. C. Gaines, Paul Gravett, Diana Green, Karen Green, Doug Harvey, Charles Hatfield, M. Thomas Inge, Leslie Jones, Jonah Kinigstein, Denis Kitchen, John A. Lent, Dwayne McDuffie, Andrei Molotiu, Alvaro de Moya, Kim A. Munson, Cullen Murphy, Gary Panter, Trina Robbins, Rob Salkowitz, Antoine Sausverd, Art Spiegelman, Scott Timberg, Carol Tyler, Brian Walker, Alexi Worth, Joe Wos, and Craig Yoe

Through essays and interviews, Kim A. Munson's anthology tells the story of the over-thirty-year history of the artists, art critics, collectors, curators, journalists, and academics who championed the serious study of comics, the trends and controversies that produced institutional interest in comics, and the wax and wane and then return of comic art in museums.

Audiences have enjoyed displays of comic art in museums as early as 1930. In the mid-1960s, after a period when most representational and commercial art was shunned, comic art began a gradual return to art museums as curators responded to the appropriation of comics characters and iconography by such famous pop artists as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. From the first-known exhibit to show comics in art historical context in 1942 to the evolution of manga exhibitions in Japan, this volume regards exhibitions both in the United States and internationally.

With over eighty images and thoughtful essays by Denis Kitchen, Brian Walker, Andrei Molotiu, Paul Gravett, Art Spiegelman, Trina Robbins, and Charles Hatfield, among others, this anthology shows how exhibitions expanded the public dialogue about comic art and our expectation of "good art"—displaying how dedicated artists, collectors, fans, and curators advanced comics from a frequently censored low-art medium to a respected art form celebrated worldwide.

Through essays and interviews, Kim A. Munson's anthology tells the story of the over-thirty-year history of the artists, art critics, collectors, curators, journalists, and academics who championed the serious study of comics, the trends and controversies that produced institutional interest in comics, and the wax and wane and then return of comic art in museums.

Audiences have enjoyed displays of comic art in museums as early as 1930. In the mid-1960s, after a period when most representational and commercial art was shunned, comic art began a gradual return to art museums as curators responded to the appropriation of comics characters and iconography by such famous pop artists as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. From the first-known exhibit to show comics in art historical context in 1942 to the evolution of manga exhibitions in Japan, this volume regards exhibitions both in the United States and internationally.

With over eighty images and thoughtful essays by Denis Kitchen, Brian Walker, Andrei Molotiu, Paul Gravett, Art Spiegelman, Trina Robbins, and Charles Hatfield, among others, this anthology shows how exhibitions expanded the public dialogue about comic art and our expectation of "good art"—displaying how dedicated artists, collectors, fans, and curators advanced comics from a frequently censored low-art medium to a respected art form celebrated worldwide.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

University Press of MississippiYear

2020Print ISBN

9781496828071, 9781496828118eBook ISBN

9781496828088PERSONAL STATEMENTS: EXHIBITIONS ABOUT INDIVIDUAL ARTISTS

Following the success of Masters of American Comics, fine arts museums and curators have shown a new interest in exhibitions by individual artists primarily identified with comics and graphic novels. This is not meant to imply that there are not astonishing historical group shows constantly being organized by collecting institutions. As I write these words in the fall of 2018, three outstanding shows are on view: Artistically MAD: Seven Decades of Satire at the Billy Ireland, Drawn to Purpose: American Women Illustrators and Cartoonists at the Library of Congress, and Sense of Humor at the National Gallery in Washington. For the purposes of this book, I am focusing here on shows following Masters that continue the fine art “lone genius” thread that was so strongly emphasized in that show. At the beginning of this section, I discuss this trend with Gary Panter, who was included as one of the “Masters,” and has been closely watching the museum and comics scene for decades.

The number and popularity of museums has exploded since the 1990s. Half temple to culture, half shopping mall, art museums are on a constant quest to satisfy their members, attract new visitors, and to fill their restaurants and gift shops. Blockbuster exhibits have become essential to the museum’s bottom line. Light years away from those hasty, tacked-up shows mounted in the 1930s, today’s exhibitions have become big investments in terms of planning, design, staffing, staging, technology, and promotion. Museums invest heavily in a few shows a year, and large institutions are especially dependant on blockbuster shows that will bring in a big audience and new members.

In the 1997 New York Times article “Art: Glory Days for the Art Museum,” art journalist Judith L. Dobrzynski describes two shows that inspired the blockbuster trend:

Back in what might be described as the dark ages for museums, they were places in which the halls literally were dark, designed for contemplation and existing primarily for elite visitors. Nothing changed that as much as the blockbuster, which brought ordinary people into museums. In popular lore, the blockbuster was fathered by the King Tutankhamen exhibition in 1977, and midwifed by Thomas Hoving, who during his time as director of the Metropolitan arranged a steady stream of them.

As Mr. Kamen [Michael G. Kamen, a Pulitzer Prize–winning professor of American history and culture at Cornell] pointed out, a lady by the name of Mona Lisa single-handedly gave birth to the blockbuster some years earlier. Leonardo’s smiling, enigmatic masterpiece was lent by the Louvre for a brief visit to the National Gallery of Art in Washington and to the Metropolitan. She was mobbed. In New York alone, more than a million people stood in line between February 7 and March 4 [1963], waiting hours to file past the painting. It was largest crowd ever for a single painting at the Met and one of the largest crowds ever at the museum, period. Museum directors took note. (1997)

Dobrzynski goes on with a description of the spectacle of the King Tut phenomenon of 1977, which spun off lucrative lines of merchandise and attracted hoards of new visitors at every museum the King visited. She spoke with John R. Lane, the former director of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, who had a theory that there were two distinct audiences that were attracted to these big shows:

One group comes to the museum “because it wants to be challenged and to see something new,” he said. “And there’s another audience, a much bigger one, that is seeking a cultural experience and doesn’t want to make a mistake. It won’t go to the Museum of Modern Art to see a Projects show for a new artist, but it will go to MOMA to see a Picasso show.” (1997)

Most comics-related shows, even Masters, may not be getting King Tut numbers, but they have always been popular with the public, perhaps because comics are such a familiar part of the visitor’s everyday lives. But it still took art museums a long time to accept that comic artists were worth risking a spot on their all-important exhibition schedule. As I’ve discussed in earlier sections of this book, there were class issues and conflicting trends in art, but another key to comics’ spotty relationship with museums was the valuation of the artwork itself. Collecting original comic art used to be a fringe activity, saving artwork from the trash; now work by popular artists like Crumb and Kirby are setting sales records. In his essay, Forbes cultural journalist Rob Salkowitz explains how exhibitions contribute to the valuation of an artist’s work while comic art continues its march to cultural legitimacy through exhibitions.

Salkowitz begins his essay by sharing his memories of the 2016 Seattle Art Museum exhibition Graphic Masters: Dürer, Rembrandt, Hogarth, Goya, Picasso, R. Crumb, which was centered around The Bible Illuminated: R. Crumb’s Book of Genesis (tour: Los Angeles; Portland, Oregon; Columbus, Ohio; Brunswick, Maine; San Jose, California; Seattle; Paris; and the 55th Venice Biennale). Comics scholar Charles Hatfield discusses his own experience viewing Genesis and the issues of narrative (and exhaustion) that come up when confronted with every page of a two-hundred-page book on the walls of the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles.

Figure 66. Exhibition view of the Will Eisner Centennial Exhibition at the Society of Illustrators, featuring a page of Eisner’s brushstrokes and ink washes. 2017. Courtesy of the Society of Illustrators.

On a smaller scale, the very personal art installations created by Carol Tyler combine comics about her family relationships and her quest to understand the trauma caused by herfather’s service in Europe in WWI using memorabilia, hand-made props, and sculptures that give the viewer insight into her mind and process. In her University of Cincinnati DAAP galleries exhibit, drawings from her award-winning You’ll Never Know trilogy wave from a clothesline, while visitors can literally walk into her head through a door cut through a large self-portrait.

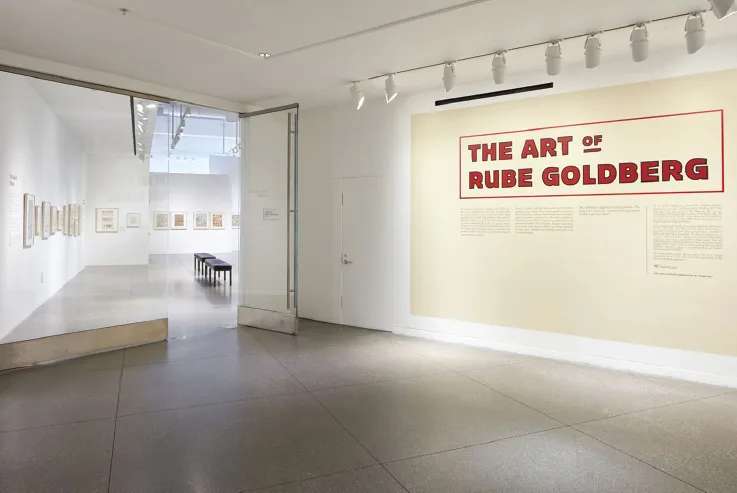

Another important trend in comics exhibits has been renewed interest in retrospectives of the work of influential elder statesmen like Will Eisner, Rube Goldberg, or George Herriman. Often filled with source materials and examples from the twists and turns of a long and wide-ranging career, these in-depth shows provide inspiration to the generations of artists following them. Impressive shows in 2017 and 2018 include a pair of centennial shows celebrating the work of Will Eisner at the Society of Illustrators, New York (figures 6, 66), and at le Musée de la Bande Desssinée, George Herriman: Krazy Kat is Krazy Kat is Krazy Kat (figures 3, 67) at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, and The Art of Rube Goldberg at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco (figures 2, 68),1 which ran concurrently with an exhibit of artist’s “contraptions.”

Figure 67. Exhibition view of George Herriman: Krazy Kat is Krazy Kat is Krazy Kat, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid. 2017. Photo by David Walker. Courtesy of Brian Walker.

An interesting variation on this idea is the artist-curated show celebrating their own comics heroes and influences. In this section, Belgian comics scholar Benoit Crucifix examines two shows of this type curated by artists Dan Clowes and Art Spiegelman. Eye of the Cartoonist: Daniel Clowes’s Selections from Comics History was shown at the Wexner Center in collaboration with the Billy Ireland (2014). Le Musée prive d’Art Spiegelman, a selection from Spiegelman’s own collection, accompanied Co-Mix, a major retrospective of his work at the 2012 Angoulême International Comics Festival (tour: Paris, Cologne, Vancouver, New York, Toronto). Co-Mix, as displayed in Paris, New York, and Toronto, was also the main topic of a conversation in a telephone interview, included here, that I had with Spiegelman in 2016.

Several recent exhibitions have explored the influential work of the “King of Comics” Jack Kirby, such as Jack Kirby: The Super Creator at the Angoulême International Comics Festival (2015), Marvel Universe of Superheroes at the Museum of Popular Culture (Seattle, 2018), What Nerve! Alternate Figures in American Art (RISD, 2015), and Masters of American Comics (tour: LA, Milwaukee, New York, Newark). The most complete of these is Comic Book Apocalypse: The Graphic World of Jack Kirby, an impressive 2015 retrospective curated by Kirby expert Charles Hatfield at California State University Northridge (CSUN). While all of these shows celebrated Kirby’s characters, distinctive drawing style, and his influence, the CSUN show also displayed the originals for an entire issue of Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth (#14, 1974) and a large selection of rarely seen collages. Ending this section is a trio of articles on the CSUN show. First, Hatfield, the author of Hand of Fire: The Comic Art of Jack Kirby (2011, University Press of Mississippi), explains his motivations and curatorial process. Los Angeles–based writer and artist Doug Harvey takes us on a tour of the exhibit in his review for the Comics Journal. Artist and art critic Alexi Worth’s review for Art in America brings us back to the relationship between comics and pop art, discussing the use of Kirby’s cover for Young Romance #26 in Richard Hamilton’s groundbreaking pop art collage Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing (1956) and Kirby’s place in art history.

Figure 68. Installation view of The Art of Rube Goldberg at The Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco. 2018. Courtesy The Contemporary Jewish Museum; Photo: JKA Photography.

Note

1. The Art of Rube Goldberg was conceived by Creighton Michael; developed in cooperation with Heirs of Rube Goldberg, LLC, New York, New York; and curated by Max Weintraub. The tour was organized by International Arts and Artists, Washington, DC.

References

Artistically MAD: Seven Decades of Satire (exhibition: May 5–October 21, 2018). Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum. https://cartoons.osu.edu/events/artistically-mad/. Accessed October 15, 2018.

“The Art of Rube Goldberg” (exhibition: March 15, 2018–July 8, 2018). Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco. https://www.thecjm.org/exhibitions/99. Accessed October 26, 2018.

Carlin, John, Paul Karasik, and Brian Walker, eds. 2005. Masters of American Comics. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Crumb. R. 2009. The Book of Genesis Illustrated. New York: Norton Books.

Dobrzynski, Judith H. 1997. “Art; Glory Days for the Museum.” New York Times, October 5.

Drawn to Purpose: American Women Illustrators and Cartoonists (exhibition November 18, 2017–October 20, 2018). Library of Congress, Washington, DC. https://www.loc.gov/item/prn-17-165/library-to-open-drawn-to-purpose-american-women-illustrators-and-cartoonists/2017–10–27/. Accessed October 14, 2018.

George Herriman: Krazy Kat is Krazy Kat is Krazy Kat (exhibition: October 18, 2017–February 26, 2018). Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid. https://www.museoreinasofia.es/en/exhibitions/george-herriman. Accessed October 26, 2018.

Hatfield, Charles, and Ben Saunders, eds. 2015. Comic Book Apocalypse: The Graphic World of Jack Kirby (exhibition: September, Mike Curb College of Arts, Media and Communication, California State University Northridge). San Diego: IDW Publishing.

Jack Kirby: The Super Creator (exhibition: February 1–29, 2015). 42th festival international de la bande dessinée d’Angoulême. http://www.bdangouleme.com/557,jack-kirby-le-super-createur. Accessed October 14, 2018 (in French).

Lind, John, ed. Will Eisner: The Centennial Celebration, 1917–2017 (exhibition catalog: Angoulême, January 26–October 15, 1917; Society of Illustrators, March 1–June 3, 2017). Milwaukie, OR: Kitchen Sink Press/Dark Horse.

Marvel Universe of Superheroes (exhibition: April 21, 2018–January 6, 2019). Museum of Popular Culture, Seattle, WA. http://www.mopop.org/marvel. Accessed October 14, 2018.

Nadel, Dan. What Nerve! Alternate Figures in American Art 1960—the Present (exhibition: September 19, 2014–January 4, 2015). Providence, RI: Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design.

Sense of Humor (exhibition: July 15, 2018–January 6, 2019). National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. https://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/2018/sense-of-humor.html. Accessed October 14, 2018.

Spiegelman, Art. 2012. Co-Mix: A Retrospective of Comics, Graphics, and Scraps. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly Publishers.

Tyler, Carol. 2015. Soldier’s Heart: The Campaign to Understand My WWII Veteran Father—a Daughter’s Memoir. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books.

After Masters: Interview with Gary Panter

Gary Panter is a prolific and multifaceted artist who is constantly experimenting and moving his art into new mediums. Building on his work in comics (Jimbo, Raw, Dal Tokyo), paintings, and design for television (Pee Wee’s Playhouse), Panter has branched out into other media like light shows, puppetry, design, printmaking, sculpture, and rock music. He has also reinterpreted the classics in a series of graphic novels; his latest book from Fantagraphics, Songy of Paradise (2017), takes on Milton’s Paradise Regained.

As he’s a veteran of enumerable exhibitions both in the United States and internationally, I was curious about his thoughts about how shows of comic art are evolving in major art museums. These comments are from a Facebook conversation we had in 2014, which have been edited for length and clarity.

Kim A. Munson: I’ve been chatting with various people about Masters of American Comics and trends in exhibitions of comics in general. One issue I’m wrestling with is why there hasn’t been another blockbuster group comic art show by the major art museums, which seem to be focused now on individuals. I asked Jeet Heer, and he said: “I think the Masters show represented the culmination and end of a way of thinking about comics history (as a story of linear progress from McCay to Ware that has now been exhausted), post-Masters there is much more interest in looking at individual cartoonists as their own thing or part of a scene—the grand narrative of comics history seems so large. As artists like Ware, Spiegelman, and Crumb get canonized, they are seen as their own thing and divorced from their comics context. So, shows like Masters, which provide context, are less valued.”

You’ve been in more group shows than I can imagine. What do you think of this? I see his point. Individual artists are easier for the museums to explain and promote. On the other hand, we don’t stop doing shows about the Impressionists as a group because we are interested in Monet as an individual. There are many eras and movements to be explored in comics and pop culture.

Gary Panter: I think that that is correct that the Masters show was an introduction to the art world of comics, another introduction. I am sure that John [Carlin] and Art [Spiegelman] would say and have said that there should be more shows along these lines. Each of us would make a different list and a different list on different days.

Institutional support and curiosity is really all that is wanted, but because of the specialized nature of comic and the multifaceted nature of genre, intent, financial influence, etc., t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Foundations: Comic Art in Museums

- Pioneers: Comic Art Exhibitions, 1930–1967

- The Renewed Focus on Comics as Art After 1970

- Expanding Views of Comic Art: Topics and Display

- Masters of High and Low: Exhibitions in Dialogue

- Personal Statements: Exhibitions About Individual Artists

- Thirty Museums with Regular Comics Programming

- List of Contributors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Comic Art in Museums by Kim A. Munson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Art Techniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.