eBook - ePub

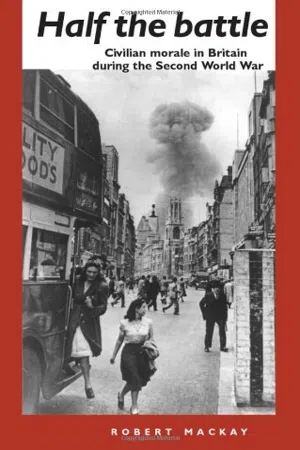

Half the battle

About this book

How well did civilian morale stand up to the pressure of total war and what factors were important to it? Rejecting contentions that morale fell short of the favourable picture presented during World War II and since, this work shows how government policies for maintaining morale were put in place.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PROSPECT AND REALITY

1

War imagined

The prospect of total war – again

IT WAS WISH fulfilment rather than realism that drove the phrase ‘a war to end wars’ into the public consciousness during the unprecedented slaughter of 1914–18. When that nightmare was at last over, there was a natural human desire to believe its like could never again be contemplated, that it really had been ‘a war to end war’. For a decade or more a traumatized mankind was in denial about its historic complacency towards the use of war as an instrument of policy. Pacifism became a mass movement of international dimensions. Millions of people, seasoned politicians among them, placed their trust in the newly formed League of Nations as their safeguard against the recurrence of the disaster of war. Nowhere was this more so than in Britain, where successive governments maintained the national role of stalwart of the League and where signed-up pacifism became a pervasive part of domestic political discourse. Its reality was manifest not just in the membership numbers of the peace associations and the official line of the Labour Party, but also in the winding-down of the defence establishment and the progressive reductions in defence spending. A country that ended military conscription as soon as the fighting had stopped and that reduced spending on the armed forces from £604m in 1919–20 to £102.7m in 1932–33 appeared to be signalling its belief that another world war was not only unimaginable but also altogether unlikely.

Within four years of that low point in defence spending the world looked a different place: economic recession had soured international relationships as governments everywhere acted unilaterally in the interest of their national economies; Japan had invaded the Chinese province of Manchuria and made it a Japanese protectorate, in defiance of the League of Nations; Adolf Hitler and the National Socialists had come to power in Germany, with all that portended for the peaceful conduct of international relations; the Italian fascist leader Mussolini had launched an aggressive war against a fellow member of the League of Nations, Abyssinia; a civil war had broken out in Spain that threatened to escalate into an international conflict. In these changed circumstances the British Government, like governments everywhere, was forced to contemplate the possibility of involvement in conflict leading to war. For the remaining years of the 1930s the overriding questions of the day were: Was war avoidable? If not, how soon might it come? How best to prepare for the contingency?

To the last of these questions the obvious answer was rearmament. And indeed from 1936, alongside a diplomatic stance designed to prevent war by appeasing the revisionist dictator governments, Britain’s leaders threw economic orthodoxy to the winds and began to spend much more on defence, focusing especially on the Royal Air Force.1

But weapons and fighting men, preponderant though they were, were not the only considerations to engage the minds of politicians and civil servants as they imagined the prospect of a Britain once again engaged in war. For modern war meant total war, that is, a war that engaged the energies of the whole nation, and not just those of the armed forces; this was not the least of the lessons of the First World War. In order to place and maintain in the field over several years armies numbering millions, governments had discovered that nothing less than a complete reorganization of the national economy was needed. Without the cooperation of the civilian population this enterprise was unrealizable. And so strenuous efforts were made to induce every citizen to contribute his energies to that unprecedented phenomenon, the ‘home front’. Thinking about future war, therefore, meant envisaging and preparing for the active role of the civilian population in the pursuit of victory. The crucial question was the willingness of the mass of the people to share the leadership’s commitment to winning the war and to bear the burdens that this entailed over a period as long as or perhaps longer than the First World War.

By 1939 this had come to be seen by the official mind as problematical. The conclusions of various committees, taking the earlier war as a baseline, had cast doubt on the ability of any government successfully to summon up a national effort like that of 1914–18 in the changed circumstances of the 1940s. In the first place, the history of the earlier conflict was as much a warning as a source of confidence. On the one hand, the people of Britain had responded to the sacrifice and effort demanded of them by the Government during 1914–18 with unselfish, patriotic ardour. On the other, the real possibility that things might easily have turned out otherwise was demonstrated by the social upheavals and collapse of the home fronts elsewhere – in Russia, Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1917–18. And even in Britain the signs of debilitating war-weariness were evident in the final eighteen months of the war. Secondly, in the years that followed the war, changes in the nature of warfare together with certain social and political developments, served to increase uncertainty about how the British people would behave in the event of another war.

Of the changes in the nature of warfare none was more significant in this regard than the emergence of the fighting air arm. In the First World War the role of airships and winged aircraft steadily grew in the four years of the conflict and in its final year constituted an important means of extending the battle zone from the fighting fronts to the home fronts. But the bombing of civilians in their workplaces and their homes, horrifying and unnerving though it was, had not been sufficiently extensive to make governments feel that civilian morale itself was seriously threatened. By 1939, however, the prospect was altogether more alarming. Aircraft design had evolved rapidly in the twenty years since the war. In every respect – speed, instrumentation and gunnery, but more significantly, in range and payloads – the machines of 1939 were greatly superior to those of 1918.2 In a number of war theatres their devastating potential was demonstrated. The first, in 1932, involved Britain’s own Royal Air Force Bomber Command: the bombing of recalcitrant Kurdish tribesmen in northern Iraq, a mission carried out at the request of King Faisal, the new ruler of this former British mandate territory. Then came the operations of the Italian air force, successfully subduing Abyssinian armies in 1935–36. Two years later German and Italian bombers were deployed in Spain on behalf of the rebel leader Franco; high profile daylight attacks on Barcelona, Madrid and Guernica were launched with impunity, to devastating effect on civilian life and property. Finally, in 1937 the Japanese air force made a series of very destructive raids on China’s coastal cities, including Shanghai, Nanking and Canton.

The record seemed to confirm that in future all wars would involve a significant role for the air forces of the combatants. It also suggested that not only would civilian populations become prime targets but that the targeting would be successful. Indeed, this had already by 1932 become received opinion in the ruling establishment, as was shown by the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin’s gloomy words in a Commons debate, ‘Let’s face it, the bomber will always get through’ – and this before the evidence of Guernica and the rest. With Germany identified – from 1935, at least – as Britain’s most likely adversary in a future war, Government thinking was that Germany would attempt a knockout blow at once, even before actually declaring war, using its total air forces, and that heavy destruction and dislocation were to be expected. As Baldwin put it, ‘tens of thousands of mangled people – men, women and children – before a single soldier or sailor suffered a scratch’.3 It was assumed, moreover, that in addition to high explosives and incendiary bombs there would be bombs carrying poison gas and other lethal chemicals. This last forecast had entered public discourse at least as early as 1927, when, in fittingly alarmist language, the MP for Oldham, Alfred Duff Cooper, warned the House of Commons, ‘Our cities will not merely be decimated but rendered uninhabitable by chemical bombs … it is not war in the ordinary sense … We are faced with the wiping out of civilisation.’4 In like manner the former head of the Explosives Department in the First World War, Lord Halsbury, was predicting in 1933 that ‘a single gas bomb, if dropped on Piccadilly Circus, would kill everybody in an area from Regent’s Park to the Thames’ – this area housed about one million people.5 Official predictions about casualties were more modest, but shocking enough, none the less. The view of the Air Staff in 1924 was that 450 tons of bombs would be dropped on London in the first three days and that this would result in 3,800 dead and 7,500 wounded. By 1937 the Committee of Imperial Defence, taking the Air Staff’s updated post-Barcelona rate of fifty casualties per ton of bombs as its guide, was forecasting 1,800,000 casualties in the first two months, one third of them killed. And in 1938 a Cabinet committee predicted that 3,500 tons of bombs would be dropped on London on the first day, 700 tons per day thereafter.

It can be fairly taken, then, that as war approached there was in official circles an accepted belief that its beginning would be marked by little less than a holocaust. What would happen next was the big question and on this there was less uniformity of view among the planners. An important influence was the experience of the First World War. Zeppelin raids on the Midlands in January 1916 had caused much public nervousness and the raids on the East End of London towards the end of 1917 had brought signs of panic among residents – ‘trekking’ out of the area and reluctance to leave the safety of the Underground railway. A report made by a Home Office sub-committee in 1924 reiterated the received wisdom of the time: ‘It has been borne in on us that in the next war it may well be that the nation whose people can endure serial bombardment the longer and with greater stoicism will ultimately prove victorious.’6 The first Marshall of the Royal Air Force, General Sir Hugh Trenchard, himself a believer in the omnipotence of the bomber, said in 1928, ‘Once a raid has been experienced, false alarms are incessant and a state of panic remains in which work comes to a standstill.’7 This was much in line with the thinking of the Italian strategist Giulio Douhet, who in 1930 attempted to popularize his views by writing a work of fiction, La Guerra del 19 – . In this he depicted a war between Germany and a Franco-Belgian alliance in which the Germans prevailed because they had perfected the use of the knockout blow from the air. ‘By integrating the aerial arm with poison gas’, he wrote, ‘it is possible today to employ very effective action against the most vital and vulnerable spots of the enemy – that is, against his most important political, industrial, commercial and other centres – in order to create among his population a lowering of moral resistance so deep as to destroy the determination of the people to continue the war.’8 Many public figures accepted the Douhet–Trenchard view. Winston Churchill, for example, predicted in the Commons in 1934 that the first raids would produce a panic flight from London of three to four million people; and the army would be too busy restoring order to do its job. ‘This vast mass of human beings’, he warned, ‘without shelter and without food, without sanitation and without special provision for the maintenance of order, would confront the Government of the day with an administrative problem of the first magnitude.’9 From another quarter came warning that alongside the problems of civilian deaths and injuries and the destruction of homes and services, would be large-scale hysteria and mental breakdown. A report produced by a committee of leading psychiatrists in the London teaching hospitals and presented to the Ministry of Health in October 1938 suggested that there would be three times as many mental casualties as physical casualties. This implied the swamping of the mental health services by between three and four million psychiatric cases.10 The most pessimistic scenario was of mass panic leading to widespread clamour for peace on any terms and of a government, because of the paralysis of its military forces, forced to give way. All this pessimism about the power of bombing was mirrored in the official policy that in 1935 made the building of a deterrent bomber force the cornerstone of defence strategy; for only, it was believed, through having the means to wreck the morale of the civilians of a continental enemy through mass bombing could that enemy be deterred from unleashing its own bomber fleet upon the British people.

A more sceptical view of the decisive role of the bomber was expressed in 1938 by S. Possony, an academic theorist on the industrial implications of war, who argued that large cities were too dispersed to be destroyed by bombing and that, in any case, aircraft were vulnerable to defending artillery and fighters.11 And not all public figures were gloomy about the moral fibre of the British people. Lord Woolton, for example, who in 1937 sat on a committee chaired by Lord Riverdale ‘to inquire into the organization of the fire brigades of Great Britain’, recalled: ‘The brightest spot in it all was that we based our recommendations on the belief that the public of Britain, faced with unprecedented calamity, would be competent and resolute.’12

But in the main, the official view on the matter tended towards pessimism. In order to explain more fully why this was so, it is necessary to return to the interwar social and political developments already referred to.

A united nation?

Raw human terror before the prospect of mechanized destruction from the air was unavoidable but, as we shall see, it was a problem for which there were practical answers: things that the Government could do to mitigate, if not to solve. What was more worrying from the official standpoint was the basic patriotic loyalty of the civilian mass. Certainly, it had been tested and not found wanting in 1914–18, but it was not easy to be confident in 1939 that things had remained unchanged. On the contrary, there were good reasons for feeling doubtful about the matter. In the interwar years love of country had increasingly to compete with other loyalties – to peace, to class, to political ideology,...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part I Prospect and Reality

- Part II Explanations

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Half the battle by Mackay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Minority Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.