![]()

1

Introduction

Agonizing health, an agonizing mental condition. Painful. Again I think about suicide. I think [about it] or does it think about me? But the ocean is splendid.

Leonid Andreev1

Interpretations

Leonid Andreev (1871–1919) was Russia’s leading literary and cultural figure from roughly 1902 to 1914. He and Feodor Sologub (1863–1927) were the best selling authors during much of that time, and Andreev was equal to Maksim Gor’kii (1868–1936) in terms of topical relevance. His name was spoken in the same breath as Lev Tolstoi (1828–1910), Feodor Dostoevskii (1821–1881) and Anton Chekhov (1860–1904) during his lifetime. Yet, because he had both supported revolution in his early years and reviled the Bolsheviks at the end of his life, Andreev found no defenders among Russian émigrés living abroad or literary scholars in the Soviet Union. Within a decade after his death, and for roughly thirty years thereafter, his literary works were largely ignored.

This book invites reconsideration of one of the leading authors of the Russian fin de siècle, concentrating on a neglected area of his life and work. Andreev was diagnosed as an acute neurasthenic and struggled with various illnesses. He gained a reputation in the popular press for being mentally imbalanced, and a recurring theme of psychopathology in his creative works seemed to support this contention. Although Andreev publicly defended his mental health, he could not escape the popular discourse that constantly conflated his life and literary works. In fact, Andreev’s personal struggle with neurasthenia2 gave him a unique perspective on the discourse of degeneration theory, which was prevalent in contemporary Russian culture, making his works particularly timely and appealing for readers. Arguably, it may have been this concentration on the decadent issues of devolution, decline and deviance that made Andreev so successful.

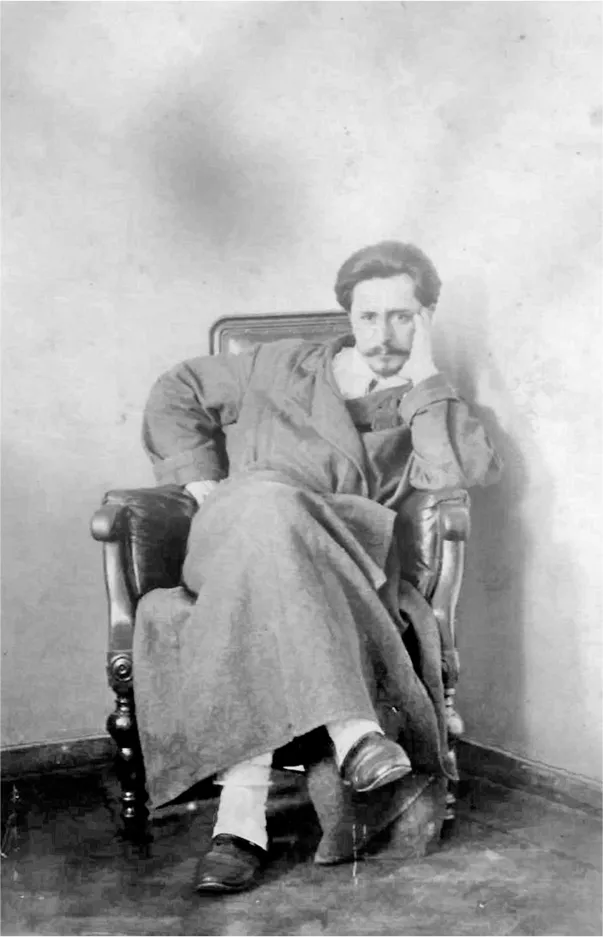

1.1 Leonid Andreev from February 1901, while a patient at the Imperial clinic for nervous disorders.

In this study, attention will be given to the way in which the discourse of a private body articulated the general anxiety around the mental and physical health of the Russian nation at the beginning of the twentieth century, providing an opportunity for a broad discussion of a medical and scientific type, which became interwoven in the fabric of Russian culture and society. Although the present study is limited to one author’s experience and the reaction of critics, medical personages and the public alike, it is meant to bring attention to some of the larger issues, around the popularization of scientific discourse at this time in Russia, issues that deserve further investigation. As such, questions will be raised concerning Russian decadence, degeneration theory, the emergence of psychiatry as a new science and the circular nature that art played in proving science correct. These questions cannot be answered completely by looking at the life and works of Leonid Andreev, but they should promote further discussion and scholarly work.

More specifically, this study examines Andreev within the context of neurasthenia, a double-edged sword that informed his literary works and impacted his personal life. This is not intended as an introduction to, nor an exhaustive biography of the author. Such works, although dated, already exist. English biographies of Andreev include those by Alexander Kaun (1924), James B. Woodward (1969) and Josephine Newcome (1973), and in Russian by Nikolai Fatov (1924) and Leonid Afonin (1959).3 Arguably, these studies do not fully reflect the possible reasons for Andreev’s immense literary success during his lifetime and certainly do not give much attention to his mental health, although Fatov here is the exception. Since the 1960s, scholars have mainly offered what might be called the sentimentalized (or sanitized) version of Andreev’s biography. Instead, this study aims to (re)establish what may be called the fourth line of medical discourse, which concentrates on the author’s life and works in the light of degeneration theory, and offers a new interpretation of Andreev’s place in Russian literary and cultural discourse within the larger context of science in Russia at the beginning of the twentieth century. Previous biographies do not satisfactorily situate Andreev within the larger popular concerns of the era, thereby ostracizing him from the period for which he was an important representative.

The approach employed in this study, illness narrative theory and medical anthropology, offers an explanation for Andreev’s perceived literary greatness during his lifetime while also allowing contemporary readers to reassess him as a talented and yet misunderstood cultural figure. Examining Andreev’s illness experience (this includes the reactions of critics, psychiatrists and the reading public) leads one to certain suppositions, not previously considered. Andreev was immensely popular because his own medical experiences permitted him to tap into the prevailing hot topic of the day – Russia’s decadent decline. The stigma of mental illness, however, seemed to tarnish his literary reputation and was denied by both Andreev and, especially later, Soviet literary scholars. In denying this, however, the contemporary reader loses all perspective on why the author was such an enormous literary success. Lost is a sense of his social timeliness, the synchronicity of his own battle with neurasthenia and Russia’s mounting anxiety about social devolution. Lost is the author’s personal struggle to maintain legitimacy and avoid the stigma of mental illness. Lost is most of the public discourse around the author and his works, which often resulted in heated public debates. Lost is the way in which his literary works were utilized by the scientific community to prove their own theories valid. Lost is much of what made Andreev a literary sensation. Remaining today is a sanitized version of the author that was mainly created to satisfy the Soviet literary market, thereby denying him his cultural relevance.4 In order to reintroduce Andreev in the 1960s, a Soviet biography was created that would focus on his revolutionary activities and concern for the common man. This version of Andreev not only distorted the author’s political views, but it obscured most of the popular discourse that made him relevant at the beginning of the twentieth century. This study attempts to recapture the discourse of mental illness that surrounded Andreev during his lifetime in order to restore to him (and for readers) a bit of that excitement and controversy that made this author the leading literary figure of his time.

After the thaw

A decade after his death, Andreev and his literary works were largely ignored, until the 1960s when Nikita Khrushchev’s (1894–1971) comparatively liberal social and political policies permitted scholars to return to forgotten authors. Once Andreev was rediscovered, concentration was directed at recovering his published and unpublished literary and journalistic works. Only recently has the scholarly gaze turned its attention once again to Andreev’s life history as a means to interpret these recovered texts. Scholars have attempted to explain the volatile emotional behavior and gloomy pessimism in the author’s literary works, diaries, letters and in memoirs dedicated to him. Logically, they have returned to many of the explanations of Andreev’s contemporaries and critics in order to gain insights.

Vatslav Vorovskii (1871–1923) and Anatolii Lunacharskii (1875–1933) offered the opinion in 1908 that Andreev simply reflected the historical milieu in which he lived.5 Georgii Chulkov (1879–1939) and Gor’kii argued after his death that Andreev’s pessimism was caused by his reading of Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) when he was a teenager.6 Andreev’s younger brother, Pavel (1878–1923), cited socio-economic factors – poverty and the stress of supporting the family after their father’s death when Andreev was only eighteen years old.7 These three lines of discourse can be used to describe one or two periods, but they fail to explain the entirety of Andreev’s life and literary output. A fourth line of critical discourse argues for an investigation of the author’s life and works in light of his medical history.8

Each one of these lines can be seen in the biographies of Andreev mentioned above. Kaun gives special concentration to the influence of German pessimistic philosophy. Afonin, Newcombe and most Soviet scholars give preference to the socio-economic pressures that they believe shaped the author. Woodward attempts to give equal time to the first three lines of critical discourse. Fatov alone gives special attention to Andreev’s medical history.

The real issue may be found, however, in the popular Andreev that existed until the 1930s and the Andreev that was resurrected in the Soviet Union in the 1960s. It is this later version that is the most sanitized and, arguably, the dullest. In order to make Andreev palatable for literary and political power brokers in the Soviet Union, much of the author’s biography was ignored or refashioned so that Andreev could be seen as a defender of the toiling masses (or, more realistic, as a representative of the radical intelligentsia). As such, scholars tended to pay attention to elements of criticism that most satisfied Marxist-Leninist theories. Consequently, controversial elements of the author’s life and works, including his battle with ill health, were repressed. Andreev’s works that could be read in a positive Soviet way were given special attention, while the author’s life was made to fit a uniform pattern, which eliminated much relevant biographical information.

Following the demise of the Soviet Union, scholars were still wary to stigmatize the author as mentally ill and, instead, refashioned once again a version of Andreev to fit the times. He was now a voice of the impending chaos and destruction of Imperial Russia. Such a scholarly position was thought to resonate with readers caught in the similarly chaotic post-Soviet 1990s. The unpleasant aspects of his character (rumors of mental illness included) were part of this zeitgeist. Specifically, concentration was given once again to the influence of German pessimistic thought as many of these philosophers were also being rehabilitated within post-Soviet intellectual society. As a result, readers and students of Andreev were left with a version of the author that was initially created for Soviet authorities and then refined to counter the overtly (and incorrect) pro-Soviet elements of this created biography. Resistance to reopening Andreev’s biography completely for discussion remains even today among scholars educated in the Soviet school, seemingly because this might tarnish once again the author’s literary reputation and diminish the work of Soviet scholars. The concern is that this version of Andreev is both dull and incomplete (not to mention inaccurate).9 An examination of Andreev’s struggle with neurasthenia asks scholars to relinquish this Soviet-like version of the author and reengage the discussion around his life and works.

From his early diaries, we learn that Andreev experienced severe depression, abused alcohol as a type of self-medication, and fixated on his relationships with various women in hopes that he could be saved from his condition. During his university years, due to the bouts of depression, Andreev tried to commit suicide at least three times and engaged in what one friend called ‘pathological drunkenness.’10 When Andreev finally began to experience literary and financial success, he was still tormented by self-doubt and depression. He sought treatment in 1901 and was diagnosed as an acute neurasthenic as attested to by his sister Rimma (1881–1941) and friend Vladimir Azov (1873–c. 1941).11 Neurasthenia, depression caused by extreme exhaustion, was included within a broad diagnostic classification for mental illness and was associated with various other illnesses of degeneration. It was this diagnosis that most influenced Andreev’s self-perception and artistic production.

To elucidate this point further, one might offer the following scenario to underscore the importance of a medical diagnosis on the life of an individual: A man visits his doctor due to a backache. After examining him, the doctor tells the man that he possibly has cancer, but would like to run more tests to be sure. For two weeks, while tests are being run, the patient’s life is completely consumed by the possibility that he will soon die of cancer. It influences his relationships with his wife and children. He begins to look at his job and the demands of his profession in a different light. He commits to exercise regularly and buys books on alternative medicine. In short, the specter of cancer influences everything that he does. After two weeks, the man learns that he is absolutely healthy and that it was just a benign tumor causing the pain that can easily be removed. But the incident serves as a wakeup call and he vows to live a more healthy life. Important here is the understanding that the man’s perception of his life was gravely influenced by the doctor’s initial diagnosis. Unfortunately, after Andreev was diagnosed, no doctor ever told him that he was healthy. Therefore, he lived as an acute neurasthenic, complicated by a variety of other health issues and, like the man who was told that he was dying of cancer, every aspect of Andreev’s life was affected by his medical diagnosis. Additionally, because of his fame, each of his illnesses was reported in the popular press as a sign of madness, forcing the author to constantly contextualize his life in these terms of mental illnesses and defend himself publicly as sane.

In this study, therefore, I concentrate on how Andreev’s life and works were influenced by the medical theories of degeneration that were gaining currency in Russian popular culture. I suggest that Andreev’s personal experience with mental illness and Russia’s growing fascination and anxiety with degeneration contributed in large part to his rapid rise to literary stardom. In turn, a circular argument was created. That is, Andreev’s personal conception of illness was informed by science, these concepts were realized in his literary works, and his works were then used as evidence that Russian society was degenerate, with Andreev serving as a prime example, thereby reinforcing the ‘legitimacy’ of the science as well as Andreev’s understanding of his own condition. This approach provides a new interpretation of Andreev’s impact on the Russian fin de siècle and addresses the role of degeneration theory in Russia at the beginning of the twentieth century. It asks that Andreev’s life and literary works be viewed within the cultural discourse of patholog...