![]()

This chapter serves as an introduction to Judaism/kosher and Islam/halal in the UK and Denmark. The main function of these discussions is to give the reader a broader historical and societal context for exploring kosher and halal in greater empirical detail in subsequent chapters; we also discuss broader similarities and differences between kosher and halal in the UK and Denmark. We firstly explore Judaism/kosher and Islam/halal in the UK before moving on to Denmark. Thus, we examine important background aspects of Judaism/kosher and Islam/halal in their national contexts and this knowledge is invaluable in subsequent chapters. Generally, compared to the UK context sources on Judaism/kosher and Islam/halal in Denmark are more limited and the section on Denmark in this chapter is to a larger extent based on our fieldwork than the UK section.

Kosher and halal in the United Kingdom

In the UK secular government predominates at a cultural level in the context of institutionally complex ties between church and state. The ruling monarch is the head of state and Governor of the Church of England, and 26 unelected bishops sit in the House of Lords. In theory, secularism does not seek to curtail religious freedoms, but to ensure freedom of thought and conscience for believers and non-believers alike. The secular and plural nature of UK society has generated competing identities for centuries and the state has a long history of accommodating religious minorities, including Protestant non-conformists, Roman Catholics and Jews (Fetzer and Soper 2005; Anasri 2009). In the 1970s, educational policy was multicultural in state-supported schools and religious education covered Judaism, Islam and Sikhism as well as Christianity. However, the arrival of Muslims in greater numbers in the second half of the twentieth century once again tested the intimate ties between church and state. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, a range of issues related to Muslim schools created wide-ranging controversy and education officials consistently refused applications for state aid, and it was not until 1998 that the government approved two independent Islamic schools. Over time Islamic practices have thus been recognised, but the constitution does not establish religious rights as fundamental and these are left to the political arena (Fetzer and Soper 2005). As we observe in subsequent chapters, current exemptions that allow Jews and Muslims to slaughter animals without prior stunning as an expression of religious freedoms continue to create considerable tension in the political sphere.

Judaism and kosher in the United Kingdom

In 1656 a small colony of Sephardi Jews was found living in London and this group formed the UK’s first embryonic Jewish community (Roth 1978). Today, outside Israel and the US, London has one of the largest Jewish populations, at around 200,000 (Kooy 2015), and a number of well-established kashrut boards and rabbinical authorities are located in the city. While Anglo-Jewry has been in decline in terms of size and religiosity for more than a century as more and more Jews have integrated, there has also been a concurrent rise in ultra-Orthodoxy in communities across the UK (Wise 2006). This is strongly evident in London and in Manchester, which has the largest Jewish community outside London and the fastest growing in Europe, with a population of approximately 40,000. Much like London, Manchester has a number of leading kashrut boards and rabbinical authorities operating at the local, national and international level.

The origins of Manchester’s Jewish population can be traced back to the middle of the eighteenth century, when a small group of Ashkenazi traders of German origin arrived in the city. By the 1780s, a small group had settled permanently and they would soon establish Manchester’s first synagogue and kosher eatery (Williams 1976). The first legal dispute over shechita slaughter in the UK was heard in London in 1788 (Wise 2006) and in 1804 local Sephardi and Ashkenazi congregations established the London Board for Shechita (www.shechita.org) (LBS). When the first synagogue opened in Manchester in 1825 the congregational shochet slaughtered animals and supervised the sale of kosher meat at licensed butchers with the authority of the ‘chief rabbi’ and a London-based Beth Din (Williams 2006).

As the economic and professional standing of Manchester’s original Jewish settlers began to improve they started to move out of the disease-ridden city centre (Engels 2009) towards the rural suburbs of Broughton and Cheetham Hill, establishing themselves as leaders of the community. As Jewish immigrants continued to arrive in the city from Eastern Europe and Russia throughout the eighteenth century the dominance of this emerging middle class became unacceptable to large sections of the community, and divisions subsequently emerged between those who wanted to retain Jewish traditions and those who wanted to modernise in line with the wider reform movement (Williams 1976). In 1858 these established–outsider relations (Elias 2008) were formalised within the community, as the Orthodox Great Synagogue and the British Reform Synagogue emerged within half a mile of each other in Cheetham Hill. A small Sephardi community of Spanish and Portuguese merchants also became established in the city during this period, yet by the end of the century these families had also started to move out to the more affluent southern suburbs, where they were soon joined by Arabic-speaking Sephardim from Syria, Iraq and Morocco. A number of synagogues thus also emerged in south Manchester, including the Sha’are Sedek in West Didsbury in the 1920s.

The London Board for Shechita – endorsed by the chief rabbi – was first given authority to grant licences to immigrant Jewish slaughterers (shochetim) in 1868 and over the coming century this was to facilitate an ongoing debate over shechita that continues to this day (Alderman 1995; Lever and Miele 2012). When the Manchester Shechita Board (MSB) was formed in 1892 to coordinate independent shechita across the city it quickly found itself defending religious slaughter from wealthy merchants and patrons of the local RSPCA (Wise 2006). MSB initially made a number of concessions to their gentile neighbours to protect the image of the Jewish community, including the adoption of post-mortem stunning (stunning animals post-slaughter) and in 1896 MSB considered using some form anaesthetic to desensitise animals prior to shechita. This was strongly opposed on the grounds that it would be difficult ascertain the exact cause of death, thus rendering the carcasses of animals treifa (unfit) under Jewish law. By the turn of the century, MSB was stuck between the two camps and they subsequently formed the Manchester Beth Din (www.mbd.org.uk) (MBD) to provide full-time rabbinical advice and religious supervision for its slaughterers and licensed retail outlets (Wise 2006).

As the Jewish community continued to spread out into the northern and southern suburbs, the degree to which Jewish customs were adhered to varied amongst different groups (Williams 1976; Wise 2006). Those who strayed too far felt the wrath of the more strictly observant and Orthodox members of the community, most notably from businessmen and textile dealers who had arrived in the city from Eastern Europe in the early nineteenth century. In 1925 this group signalled their opposition to the erosion of traditional Jewish practices by forming the Machzikei Hadass (MH) society. From this point onwards MH became the centre of strict Orthodoxy in the city through community activism and repeated demands for higher kashrut standards, yet it was not until 1965 that the chief rabbi agreed to license an independent MH shochet to conduct shechita. In Manchester today both MBD and MH offer shechita services.

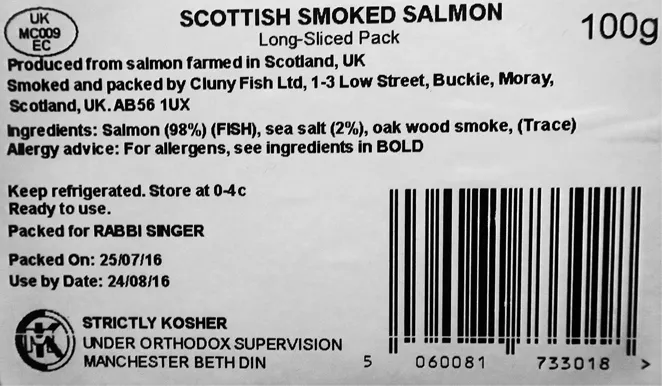

In recent decades MBD has become a well-established kashrut organisation at the local, national and international level. The organisation supervises companies in Europe, the United States, China, India and Japan, amongst other places, and the Manchester Kashrus (MK) stamp and hechsher is visible on hundreds of food products at major global companies such as Kellogg’s, Heinz and Kraft. Kellogg’s Trafford Park factory, not far from Manchester United’s famous Old Trafford stadium, is the biggest cereal factory in the world and produces 1 million boxes of cereal a day – around 400 million boxes a year (Kalmus 2012). All of the cereal produced at the factory is now kosher-certified, including over 30 of the 100 Kellogg’s products currently manufactured in the UK. Kellogg’s first started thinking about kosher certification in the late 1970s. At this time they spent a couple of hours every month producing cereal for Israel, which meant that they had to close down production completely at great expense to comply with kosher requirements and a decision was eventually made for the factory to go completely kosher.

Rabbi Osher Yaakov Westheim – a former senior dayan at MBD for around 20 years – explained to a researcher that this change in production was not without its problems. As some suppliers could not supply the gelatine-free vitamin mixes (derived from non-kosher animal ingredients) required for kosher production they often became uncooperative and secretive. To complicate matters, when MBD auditors were trying to work out where various ingredients listed on Kellogg’s products originated – vegetable oil in fried banana chips from the Philippines, for example – the company sometimes couldn’t provide the information they required. In other instances Kellogg’s had added ingredients to products as experiments, which often carried on for a number of years when it was totally non-effective: on occasions MBD thus made Kellogg’s aware that they would save considerable amounts of money by eliminating such ingredients from production. Rabbi Westheim claimed that the Kellogg’s operation was thus a significant turning point in MBD’s reputation and that from this point onwards they ‘grew into a major setup’, earning ‘a reputation of being high-standard kosher’.

During a recent spot check and visit to Kellogg’s Manchester factory, another former MBD dayan, Rabbi Yehuda Osher Steiner, inspected a series of large machines in the enormous five-floor factory where ingredients are sorted; before he entered the factory, MBD has already checked the ingredients used in production from hundreds of sources and dozens of factories. While many of the cereals inspected by Rabbi Steiner are vegetarian, he points out that this this does not ensure that they are fully kosher. In relation to Fruit ’n Fibre, for example, he states that: ‘You’ve got the raisins and sultanas, which kosher laws have to ensure have no problem of insect infestation, and that coatings on raisins are vegetable oil and not the animal derivatives used by some companies’ (Kalmus 2012). After the inspection of these machines is complete, Rabbi Steiner moves on to oversee the ‘kosherisation’ of equipment to prevent contamination by way of non-kosher infusion. In a huge hall on the fifth floor of the factory there are over 20 rotating cylindrical pressure cookers cooking millions of corn grits using steam, which, the rabbi explains, has the potential to create many problems for kosher production. On the third floor, where Corn Flakes are toasted, flavoured and tossed on conveyor belts on their way to giant mixers upstairs, engineers are again consulted to understand the heating process (Kalmus 2012; see also Blech 2008). Taken in its entirety, this is a comprehensive process and to a get an overall picture of production at Kellogg’s Rabbi Steiner must speak with engineers in many parts of the factory.

The processes involved in kosher production are also increasing in complexity. Food production is changing rapidly and informants suggested that as well as opportunities this presents many challenges from a kosher perspective. While 50 years ago an individual food product might contain between five and ten ingredients, today it might contain over a hundred. Not surprisingly, as we observe in subsequent chapters, MBD offers certification for innovative UK biotech companies manufacturing enzyme blends for food and non-food products globally.

As property prices in London have continued to rise in recent decades, the Manchester community has grown considerably, becoming more strictly Orthodox in the process (Wise 2006). Between the population census of 2001 and that of 2011, the predominantly and strictly Orthodox haredi ward of Sedgley in Greater Manchester grew by almost 42 per cent (Graham 2013). When the leading historian of haredi Judaism in Manchester, Yaakov Wise, moved back to the city from London in 1991 he explained that there were very few local kosher restaurants and takeaways. Today, a quarter of a century later, the north Manchester community has a wide range of eateries, bakers, delicatessens and other businesses certified by MBD (see www.mbd.org.uk/site/licensees). More recently, as the community has become more strictly Orthodox, the mehadrin hechsher (which designates more meticulous observance of kashrut laws and shechita practice) of the Machzikei Hadass Kashrut Board has become increasingly visible, with a number of our informants explaining that strictly Orthodox Jews will not buy MBD-certified products or go anywhere near a supermarket to buy kosher food: Yaakov Wise confirmed this trend, pointing out that he only eats glatt kosher from strictly Orthodox sources. While the expansion and development of the kosher market in Manchester mirrors the growth of a more Orthodox and demanding community, Yaakov also notes that young people have more disposable income than they once did and hence like dining out more than the older generation. Growth is also part of the trend towards middle-class suburbanisation, even within the strictly Orthodox community (Wise 2006).

Halpern’s Kosher Food Store and Delicatessen – one of the leading kosher businesses in the UK – is an MBD licensee. Located in Broughton near the Salford–Manchester boundary, the business has origins that stretch back three generations, and since opening as Higgins in 1924 the name of the business has changed three times; in 1951 Shimon Halpern purchased the shop and it retains this name. From 1983 to 1993 the shop flourished under the ownership of David Weisz and this has continued since David Salzman and his wife bought the business. Salzman explains that Halpern’s mainly sells fresh and frozen meat and poultry, and also cold cuts (processed meats), predominantly under local kosher certification from MBD and MH. However, he also points out that Halpern’s has to provide as wide a range of kosher certification as possible, as this has been paramount to their success over the last 90 years. Recognising that the strictly Orthodox community has grown significantly in the last couple of decades, he argues that this continues to create increasing market growth for kosher brands and kosher certification. As well as the smaller kosher shops, David points out that mainstream supermarkets in the area have also recognised this change and increased their selection of kosher food products. In line with trends amongst the general public, David suggests that healthy eating is becoming a more prominent factor for kosher consumers and for the business. Halpern’s own-label Deli’n’Dine fresh food products are free from colourings and preservatives and are very popular within the Jewish community, offering a range of traditional and Middle Eastern cuisine to address the demands of both the Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jewish communities.

Kosher food is now widely available in public institutions around Manchester and Salford. A number of informants explained that some mainstream Jewish schools in the UK provide kosher food from recognised certification bodies: some schools serve pre-packed kosher meals from the company Hermolis (www.hermolis.com), which provides kosher meals for British Airways. Many Jewish schools in north Manchester also provide their own kosher catering. This wasn’t always the case. One informant from south Manchester noted that when he was a schoolboy in north Manchester in the 1950s he travelled for lunch every day to a kosher canteen in Salford that fed Jewish children from regular primary and secondary schools across north Manchester. While some informants argued that provision could be better in public institutions, others pointed out that if stric...